There will always be a robust amount of free content on Street Stack, but if you’d like to support the considerable time it takes to write these posts, an upgrade to paid would be much appreciated!

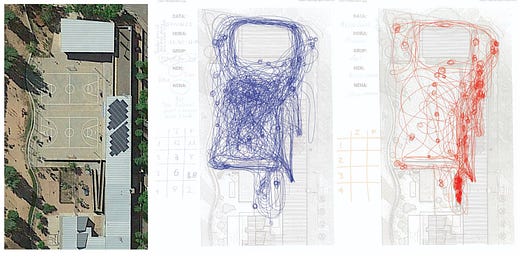

Who is the city for? Researchers in Spain observed boys and girls moving across a schoolyard during recess for two years and created a series of visualizations. There is a clear gender divide between where the boys (blue) and girls (orange) gather and move.

Boys dominate the center of the yard where concrete soccer pitches are, while girls cluster around the periphery. Most sports require a large amount of space, but is it fair to design half the schoolyard for an activity that’s dominated by boys? What conclusion should we draw from the gender divide? Is it that the space is badly designed, or that not enough girls are encouraged/welcomed to play soccer? The answer is probably somewhere in the middle, but this playground illustrates a common planning problem, balancing the needs of different groups within the same space.

Planning is future-facing, requiring us to envision an outcome that doesn’t exist and plan how to get there. Envisioning the future of flood resilience or frequent transit is relatively uncontroversial, but envisioning who a space is for is tricky. Cities are planned for specific groups, even their seemingly innocuous aspects. I once saw an elderly man with a cane begin to cross a four-lane road right when the crossing signal turned to ‘walk.’ The timing of the signal was clearly designed for someone walking at ‘average’ speed because, by the time the light had switched, he was not fully across the street. The women in my office used to complain about how over-air-conditioned our space was in the summer because believe it or not, many building codes require ambient temperatures that are based on the metabolic rates of men.

These examples show the obvious— different groups experience space differently, which is why the audience question is so thorny. Who do you cater to? Embedded in these different experiences are also power imbalances. The writer Dolores Hayden wrote extensively about how suburban sprawl reinforced the gender divide. To avoid man-splaining feminist planning and architecture, I will quote at length from her excellent 1980 journal article on non-sexist cities, which I encourage people to read.

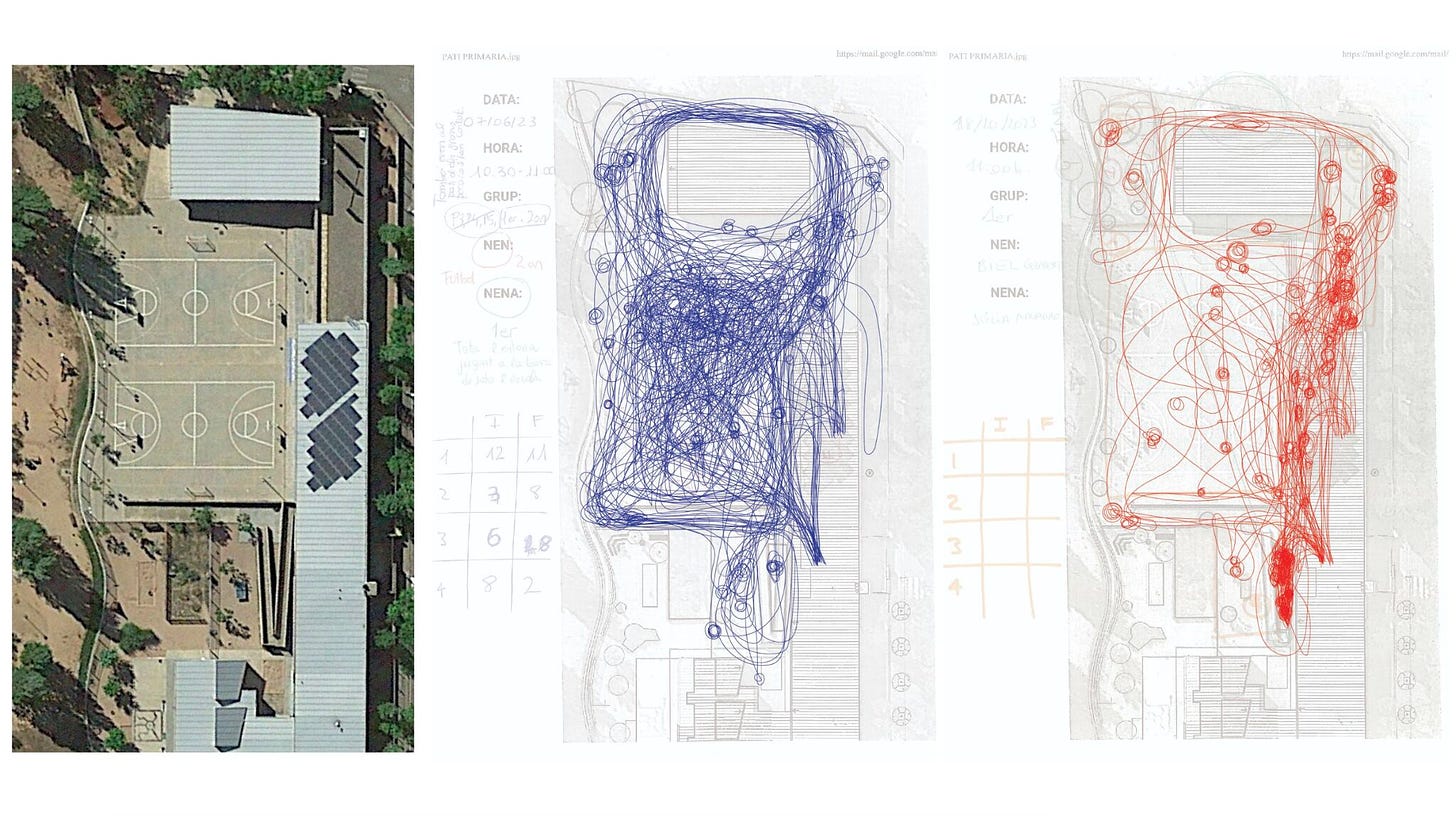

How does a conventional home serve the employed woman and her family? Badly. The house or apartment is almost invariably organized around the same set of spaces: kitchen, dining room, living room, bedrooms, garage or parking area. These spaces require someone to undertake private cooking, cleaning, child care, and usually private transportation if adults and children are to exist within it. Because of residential zoning practices, the typical dwelling will usually be physically removed from any shared community space-no commercial or communal day-care facilities, or laundry facilities, for example, are likely to be part of the dwelling's spatial domain.

Within the private spaces of the dwelling, material culture works against the needs of the employed woman as much as zoning does, because the home is a box to be filled with commodities. Appliances are usually single-purpose, and often inefficient, energy-consuming machines, lined up in a room where the domestic work is done in isolation from the rest of the family.

To Hayden, suburban sprawl and its attendant consumerism kept women isolated, dependent, and in an age where they were expected to work outside the home as well - frantically busy. Hayden loosely designed a series of interventions that could be grafted onto a suburban neighborhood— moving laundry, cooking, and childcare out of the home and into shared facilities to cut down on the time commitment and loneliness induced by domestic work, and combining backyards into communal play areas to increase social interaction among homemakers and allow one person to informally watch several neighbors’ kids at play.

Beyond gender, LGBTQ groups are another example of how identity shapes the use of space. Historically, LGBTQ relationships had to be initiated covertly, often in liminal public spaces like parks, piers, and bathhouses. It also led people to settle in red-light districts such as Sands Street by the Brooklyn Navy Yard (perhaps NYC’s first gay neighborhood), where the law and the general public were already turning a blind eye. Over time, discretely LGBTQ neighborhoods like the Castro and West Village emerged.

The writer Petra Doan explains planning’s uneasy relationship with this audience and charting its future. On the one hand, Doan points out that cities have targeted “gay villages” (as she calls them) for “cleaning up,” and gentrification has further eroded the character of many of these neighborhoods. To rectify these wrongs, it would make sense for planners to keep an LGBTQ audience in mind for these areas. On the other hand — should planning efforts be spent on keeping “gay villages” gay when the reason they emerged was that LGBTQ people were excluded from other neighborhoods? Is true fairness an even distribution of gays over the entire city!?!? Doan concludes that because LGBTQ people require specific centralized city and social services, share history and culture, and (like any group) generally like to get together, the gay village is still relevant, and planning should be done specifically for the LGBTQ community. This suggests there is a sort of bar that groups have to meet before their needs are uniquely considered.

Where the bar is, is often fuzzy. NYC recently allocated 53 million dollars to renovate a plaza in Manhattan Chinatown to include a ceremonial Chinese arch. The city has decided that maintaining the ethnic character of this area is investment-worthy. But Chinatown itself emerged from a neighborhood that was once called “Little Germany,” and then became mostly Eastern European, and right now the Chinatowns in Brooklyn and Queens are exploding organically. Why are we trying to lock in one specific ethnic identity in an area that has had dozens if not more of them? Wouldn’t a better solution be spending that money on what’s actually driving Chinese people out, which is the wild unaffordability of the City? This is the real reason the Lower East Side has been the historic landing pad of immigrants (it was cheap and well located!). Our mayor is more concerned with the Disneyland aesthetic of an ethnic enclave than addressing the forces really pushing people out, but I digress.

One audience stands head and shoulders above the rest when it comes to planning, and that’s rich people. Writers like Richard Florida and Edward Glaeser convinced people like Michael Bloomberg and Boris Johnson that the success of cities depended on how well they could cater to a very narrow subset of well-paid tech and financial services workers. These workers liked cool coffee shops, walkable streets, high rises, and chic restaurants. I could write an entire post about the class audience of planning, but sufficed to say the entire post-2008 idea of urban development, from tax policy to the types of stores that pop up, to architectural style, has been geared towards attracting high-paying office workers and their employers to cities. Many of these policies have over time proved to gut city services and drive income inequality. A plan’s audience is often shaped by power, if your little group has influence and money they usually get planned for.

I’m bringing up class, gender, and sexual orientation just to show all the various lenses you could use to answer the question of who is this space for.

Given how complex the question of audience is, how easy it is to mess up, and how unfair it can be, it’s not surprising that some question the entire premise. The architect and critic Michael Sorkin lamented that many architectural and planning movements seemed concerned with producing an “ideal type” of person. Modernists wanted to make efficient and slick places that produced efficient and slick men. New Urbanists wanted almost sleepy, village-like towns that produced a society of neighbors with traditional family values. If our imagined audience is too narrow, too idealized, or reduced to tropes and stereotypes, we may end up squashing the very diversity that makes cities fun.

I’d suggest that one way to address the differences between groups is to plan around their similarities. We all have bodies, many of us need to care for children, and we would all be worse off getting hit by a car. This isn’t to suggest that planning for the unique needs of highly specific audiences isn’t necessary in some cases, but focusing on universal human truths is one way to prioritize limited planning resources. Another is to look for improvements that may be targeted at one group but happen to benefit everyone. For example, the City has been steadily adding curb ramps to street crossings so people in wheelchairs can traverse them. These ramps inevitably end up helping not only people in wheelchairs, but the elderly and small children as well who don’t have to mount a curb. Better street light design has been shown to increase women's and girl’s perception of street safety, but these same improvements also benefit people with inhibited vision and … shockingly, men, who also have eyes.

I’m not really answering my own questions in this post. The audience issue will continue to be vexing because planning a city means, as the writer Howard Gillette put it, dealing with people “in all their messy, squealing, and delightful differences.” Part of the fun of working (and living) in cities is the sheer diversity of hopes, dreams, and realities you are dealing with and planning for every day, and defining your audience will always be both imperfect and necessary.

Wow, Dolores Hayden. I read her in graduate school, many years ago. Great stuff. And a great post.

Really enjoyed this, thanks!