Why Do You Hate the Bus?

We could have starchitect-designed nationalistic buses instead we have crap. What US transit might learn from the Routemaster.

I adore a specific model of London bus, the New Routemaster. I love its rounded edges and the way the swooping ribbons of glass follow the movement of people on the staircases. The buses are filled with light and its upper-level windows are the best cheap way to see the city. I’m shameless in my belief that things the public uses every day shouldn’t just work well, but also be nice. The Routemaster ticks that box.

But this specific bus has a strange history. It was designed by Thomas Heatherwick, the sort-of-artist sort-of-architect billionaire whisperer. He’s best known in the States for designing the Vessel in Hudson Yards, a 75 million dollar sculpture in the form of a staircase to nowhere which instantly became a popular place to commit suicide and had to close. Heatherwick won a competition to create a new public bus dreamed up by then Mayor of London Boris Johnson. Johnson would become one of Brexit’s primary cheerleaders and serve as Prime Minister during the UK’s succession from the EU. He is also a bus nerd, who admits he relaxes by building model buses in his free time and has an almost uncontrollable nationalistic nostalgia for a specific model of London Bus, the Routemater. Here he is holding one during his election campaign. No idea if this is a model of his own making.

For decades the Routemaster was the quintessential London bus, with its two levels and rear door for hopping on and off. In his run for mayor, Johnson promised to eliminate the articulated buses that had recently been introduced from Germany and replace them with one custom-made for the British capital.

The articulated buses were “whales,” ugly, and also “too European,” he mused in his newspaper column. Where had London’s swagger gone that it was importing buses from Germany? Johnson wrote nostalgically about hanging off the back of Routemasters as they tooled around and mused in a column that a new hop-on hop-off bus would bring confidence and energy back to the capitol still reeling from the recession if only it could free itself of those dam German buses. It’s not hard to see an early version of his Brexit messaging in all this bus angst.

Upon his election, Johnson made good on his promise and held a competition to design a new bus. The guidelines were light on operational concerns and heavy on aesthetic ones. The bus had to be red, had to be double-decker, and had to feature an open back entrance that could facilitate the hop-off feature. The winner was the elegant design from Heatherwick. The magazine Autocar declared “This country has again shown that it can leap into the future, by adopting the best of the past,” and even the left-leaning Guardian had to admit that the bus was a beauty. Operationally however the bus was less successful. The rear doors, the spirit of the entire Routemaster enterprise, proved to be economically unviable since they required a bus conductor to operate properly in addition to the driver. Doubling the labor force on each bus proved to be financially impossible without an unpalatable fare increase, and the buses were soon running with their rear doors firmly closed. New orders were halted in 2016.

There is a lot to read into this whole episode. But, as an American, the strangest thing to me is the view that the bus is worthy of high design and fanfare in the first place and that an upper-class, Oxford-educated, conservative politician actually expended considerable money and political capital on a bus for the masses.

This surprises me because Americans, by and large, hate buses.

There’s an episode of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia where Dee is forced to take the bus because Denis and Mac ruin her car. “Do you need to breathe directly into my mouth?” She asks a man standing painfully close to her. After forcing her way through the crowd to the front she confides in the driver, “freakshow back there. As you can probably tell I’m not a bus person, but a couple of dicks destroyed my car and forced me to lower myself to this.” Transportation journalist Will Doig stated in 2012 that “not liking the bus is practically an American pastime.”

This is not the global status quo. In Brazil, the Southern city of Curitiba pioneered a “Bus Rapid Transit” system, where buses run in long chains over dedicated lines making them more like trains on wheels than buses. The BRT model revolutionized the local economy and spread across Latin America inspiring copy-cat systems as far away as China. These buses are sleek symbols of modernity in the cities they serve. London and Hong Kong’s double-decker buses are up there with Big Ben and The Bund as symbols of the city.

Hating buses is hating one of the greatest tools in the mass-transit arsenal. Unlike trains, buses can climb hills and navigate sharp corners. They are relatively cheap, and able to run on existing roads without billion-dollar tunnels and stations. They can be electrified or run on hybrid engines. With the right design (dedicated lanes, priority at intersections) they can run at speeds that approach metro and light rail. Bus networks are flexible, stops and routes can be moved in a way that a fixed train stop cannot. A future in which people give up their cars for sustainable public transportation probably has a lot more buses than subways.

So why isn’t America on board?

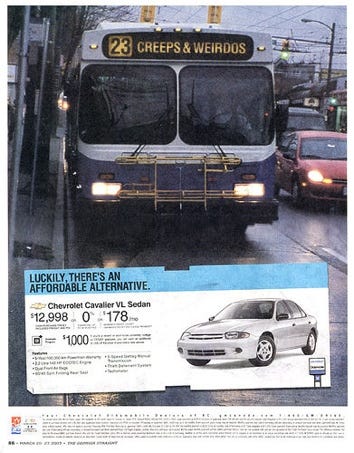

Stigma is part of the answer. Writer Amanda Hess captures a common sentiment when interviewing a former car-owning bus rider who says, “I think there’s a social understanding and a construction around that if you take the bus, you take it because you don’t have money.” Bus riders tend to be older, poorer, and more non-white than their counterparts in trains and cars. In 1977 minorities comprised 21 percent of bus riders, by 1995 it was 69 percent. In 2019, the ridership of the country’s largest bus system in New York City was 60 percent nonwhite, while for subway riders it was 53 percent. These trends mean that over time racist and classist undertones have come to infuse criticisms of buses from pop culture to advertising to public hearings. In 2003 General Motors was forced to pull an ad that showed a bus labeled “creeps and weirdos,” and offered a Chevy as a means of escape.

Hess describes a public hearing in Tempe Arizona where a new bus line was greeted by residents with concerns about the “bums,” “drunks,” and “Mexicans.,” who would soon be carted through the largely white suburb. There are people we don’t like on the bus… it’s not hard to see this uniquely American disdain carry from Rosa Parks to now.

We also don’t like buses because they don’t work well here. When something overwhelmingly serves poor people it becomes very easy for the government to ignore. At a municipal level, cities often direct federal transit dollars towards flashy rail projects over the buses that serve their less powerful residents. The most incredible example has to be when a bus-rider advocacy group successfully sued Los Angeles’s public transportation authority in 1995 for bias in its budgeting and investment policies. LA had allocated nearly 70 percent of its budget to servicing a light rail system that served only 6 percent of public transportation users. The 6 percent were overwhelmingly white, while the other 94% were bus riders who were mainly Black and Latino. All this adds up to a vicious cycle of disinvestment. Officials reading the negative climate around buses deem it unworthy of funding which only compounds its woes. Bus riders who tend to be drawn from disenfranchised segments of society lack the political power or clout to advocate for more investment. Many cities that made substantial bus budget cuts to respond to the 2008 recession never meaningfully restored service only to be confronted with a new crisis in the form of COVID. Even before the COVID pandemic, ridership had been declining nationally since 2012, and even longer in some major metropolitan areas. Biden’s Infrastructure bill was a bonanza for rail and electric car funding, not so much buses.

AND YET. The bus is still the most used form of public transportation in America, so improving public transit should start there. You can read somewhere else about the nerdy ways we can make buses better by speeding them up. My bold idea is lets borrow from Boris Johnson (in this one, very specific way and in no other way at all) and make the bus sexy. In fact, making the bus sexy and making it work well can be the same thing.

Ironically America’s hottest bus might come from Los Angeles, I guess that lawsuit was a real kick in the pants. Here is LA’s G line.

Dare I say it’s got a streamlined Art Deco vibe to it. These buses run in their own, track-like separated lanes making them speedy. The covered wheels almost hide the fact it’s a bus and the G line is given the same visual treatment on system maps as the light rail lines. The overall effect is a bus that in branding and shape seems like it’s trying to disguise itself as a train. The sight of an aerodynamic, train-like bus gliding next to you in its own lane while you sit in traffic is a powerful advertisement and costs zero marketing dollars after the vehicle purchase. Research backs this up. Transit researcher Alasdair Cain conducted focus groups with LA commuters and found that several of them switched to buses after seeing the G line vehicles. The G line has the second-highest customer satisfaction score of any of LA’s transit lines, and yes that includes rail lines built for twice as much money.

Transportation is x’s and o’s and math and engineering, but it all serves people, and people are emotional creatures. Herbert Gans once said that “all humans have aesthetic urges; a receptivity to symbolic expressions of their wishes and fears.” If you want proof of this, then consider our favorite form of transit, the car. It’s not by chance that large swaths of people have come to believe they need a military-grade pickup truck even though they live in a suburb and send emails all day. Car companies have used 100 years of marketing and design-driven myth-making to sell the car as the symbol of rugged individualism and self-reliance, the pickup is just the latest flavor of that. Can public transit satisfy an “aesthetic urge?” I think so. In the early 1900’s people were vehemently against the proposed Paris Metro. They thought it would be noisy, dirty, unsafe, an industrial stain on their beautiful city. In the face of stiff civic opposition, architect Charles Garnier advised the government that the key to getting Parisians to accept the trains as if they were turned into a “work of art.” If the train couldn’t match the prestige and freedom of your own horse and buggy, maybe it could be the most cosmopolitan way to get around. A competition was held to design entrances to each Metro station that signaled the progressive and welcoming nature of the Metro. The result was the sinewy art-nouveau entrances the system is famous for now, whose flowers and curves are anything but industrial, and the rest is history.

This is fascinating. I generally hate buses as much as I hate cars--rubber-wheeled transportation makes me (literally) queasy. Hence I love trains and walking. Still: "We also don’t like buses because they don’t work well here. When something overwhelmingly serves poor people it becomes very easy for the government to ignore." Such a good point.