London is full of memorials, the biggest are for the World Wars, followed by the Napoleonic Wars. Then there are your B-tier wars, like the Ten Years War, Hundred Years War, The Anglo Russian War, and on, and on. I'm not exaggerating when I say I probably discover 2-4 new wars the British have fought every few weeks just by walking around and reading plaques. While it can feel like London is draped in blood and glory, many memorials are dedicated to conflicts of dubious moral standing (the conquest of India, the Opium Wars, etc.), and you do eventually sort of tune them out. Given all the war and conquest, it was disarming to happen upon a very different memorial recently: the National COVID Memorial Wall.

It's a simple thing: thousands of red hearts painted on a wall outside St Thomas Hospital facing the Thames River, just across from the Houses of Parliament. Each red heart is open for someone to fill in with the name of a deceased loved one. The site is maintained by volunteers. This is not high-design; it's basically an officially sanctioned DIY memorial. However, I found it touching precisely because it was DIY. People wrote in their own words, with their own flourishes and mementos, a message to a departed loved one. Because it's on the river, you can't approach the memorial head-on. You are forced to approach it from the side and walk its full length past all the names, an effect Maya Lin’s design for the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington D.C. deploys to great effect. It takes a good 8 minutes or so to walk the length.

The memorial doesn’t claim to be exhaustive, but its scale, and the scale of human loss it represents, is powerful.

The experience prompted me to contemplate the role of memory and tragedy in shaping a city's identity. For better or worse, cities are often defined by their tragedies. Until I lived here, I never truly grasped how extensively London was bombed during World War 2, a period that has nearly vanished from living memory but is still apparent in the bomb scars on buildings and places like Earl's Court or the Barbican Centre, constructed on the ruins of bombed-out neighborhoods. The bombing gave rise to the "Keep Calm and Carry On" attitude that Londoners like to invoke. When the Queen addressed the nation at the height of the UK's COVID lockdowns, she remarked that the spirit of stoic resolve reminded her "of the very first broadcast I made in 1940" to children evacuated from London during the Blitz.

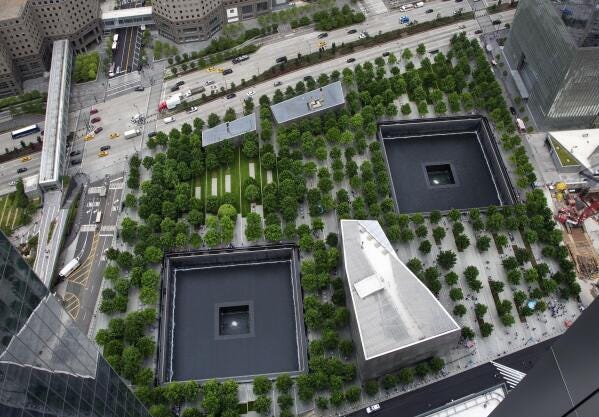

There is a curious symmetry between how people treat the bombing of London and 9/11. “New York Strong,” and “Never Forget.” Our reputation as a resilient city full of tough but caring people comes from the response to this tragedy (whether we live up to that self-image is another story). 9/11 also resulted in New York’s most prominent memorial, the National 9/11 Memorial in downtown Manhattan.

Cities are interesting grounds for memorializing. The writer Mark Harris once said

Large cities make good homes for memorials, in part because all cities are themselves dynamic, teeming memorial sites — every sidewalk, every store, every high-rise is constructed atop a spectral earlier version of itself where generations before ours went about their days. Manhattanites live on a street grid that in some downtown areas has been in place for 200 years or more, and pretty much anyone in a metropolis crosses every street in the paved-over footsteps of the dead.

But pulling off urban memorials is tricky.

They must convey history without themselves being historical artifacts.

They must convey not just the facts, but also elicit emotions

They must be physically suitable for private and collective mourning

If they’re done in cities, they must exist respectfully alongside normal city life.

I’ve never liked the 9/11 memorial because it fails the last two bullets. It’s too big and exposed to allow peaceful reflection, and its location adjacent to the offices in the Freedom Tower and Brookdale Center meant it would always be treated as a pass-through by thousands of workers and tourists everyday. Its vastness makes it awkward to gather around, and by taking the shape of the towers’ footprint it feels in many ways like a memorial to the buildings not the people. It also made permanent the scars of the attack. What was once a hub of activity is a lifeless void, a literal black hole. I find the temporary activities, like the projection of huge beams of light (although these kill a lot of birds), and the ringing of memorial bells, to be much more poignant.

This year nature added its own flourish when a stunning double rainbow appeared on the day.

It was a good reminder that some of the best memorials are ephemeral. The ubiquitous Ghost Bike is a good example.

This year’s 9/11 commemorations struck me more than they usually do. Maybe its because the City is on a bit of a downward trend. When the mayor isn’t dodging the FBI he’s announcing a fresh round of budget cuts to essential services. The City only just recovered all the jobs it lost during COVID. We have the worst wealth inequality in the US and data indicates that the COVID economy made it worse. Remembering 9/11 is painful, but it also gives perspective. We’ve been through tough times before and we’ve come back.

The public memorializing of 9/11 was almost instant, but its been three years since the peak of the pandemic and no one seems in a rush to start any public tribute to the eighty thousand NYC’ers who died of the virus since it hit. The 7 O’Clock clapping is over and the pots and pans have been put back on the stove. So why, despite being the deadliest single thing to happen to NYC, is there no COVID memorial? Did any of that happen? Some people would point out that its difficult to memorialize something that’s still happening. People die from COVID everyday. I reject this excuse because I think everyone knows that even if the disease is endemic and just a part of life now, 2020 was extraordinary.

I think the deeper reason is that COVID boggles our minds, and so forgetting feels easiest. Wars have human victims and human perpetrators. They are relatively tidy stories. COVID is an invisible, unfeeling, and unthinking force of nature, and the fights about vaccines and masks, the conspiracy theories, the drastic changes to work and life, are all wound up in the loss of life and maybe these are things we would like to forget. The London Memorial is so powerful because it ignores most of this. Its so immensely personal, so laser-focused on the human loss that the societal baggage of the virus fade away. More importantly it makes the invisible visible. Most people never saw inside a COVID ward, many digested the virus through screens from the safety of home. Three weeks into lockdown I went for a bike ride in Manhattan. I rode the wrong way on a deserted Park ave for 20 blocks. For most of the ride it was just me and the amazon delivery guys on the street. I had been doom-scrolling the Times and watching every Cuomo briefing but nothing prepared me for running into a line of freezer trucks parked outside Bellevue Hospital, ostensibly full of bodies from the overflowing morgue. Holy shit, this is happening. Most people need to see something to really feel it. Memorials transport this power. Every death in lockdown happened in private, which makes public memorializing so important. A quotes from someone who dedicated a heart on the wall:

“Where losing someone this way has been very isolating for many different reasons, the wall is a reminder we aren’t alone.”

New York deserves the same. If tragedies define cities so should this one. COVID was miserable, but just like 9/11 it also showed the best of us. Mutual aid, transformative placemaking, a serious (although fleeting) public appreciation for the working class people who keep the city running. We feel trapped in a downward cycle. A memorial won’t solve the tangible ways we are still stuck in the pandemic era, the stuttering economy and over-stretched public sector, but it would make us stronger is other ways.

If I was the Mayor…

Some quick, loose thoughts on a proposed COVID memorial for NYC.

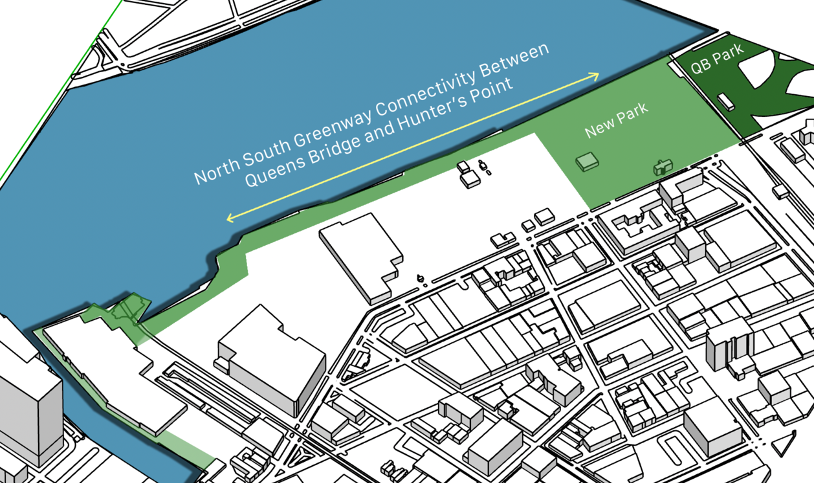

I would put the memorial in Queens. When NYC went into lockdown, Queens went to work. The 7 train stayed busy serving nurses, sanitation workers, delivery drivers, and other now-forgotten essential workers when large swaths of the city sheltered in place. The City Comptroller estimated that 2 million essential workers live in Queens, and the borough had the highest number of deaths as a result.

I even picked a site. A big empty slice of land on the East River you can see below. The views here would be stunning, and it would be visible form Manhattan, the Queensboro bridge, and at certain scales and vantages would be visible from the UN and the upper floors of the east side Manhattan hospitals that formed the national front-line against the pandemic in its early stages

Right now the site is partially owned by the City, and the rest is a parking lot used by Con-Ed.

In terms of what would go there, I’ll leave the design to the designers but I think our COVID memorial shouldn’t be a big stone thing, it should be a park, or at least a greenspace. The park was our gym, our meeting room, our opportunity to just be near people again. I like the idea of a useful memorial. One of my favorite memorials is in Hawaii, the Waikiki Natatorium, a World War One memorial built in the form of a public ocean swimming pool.

Practically, a waterfront park would also link existing greenspaces by the Queens Bridge houses and Gantry State Park to the south. The site is also within the Hurricane Sandy Inundation Zone and vulnerable to flooding so a greenspace could be designed to absorb flood waters and confer resiliency benefits to the wider area.

The idea of a memorial park is powerful in its tension— a place of vibrancy, socializing, and nature is also a monument to the city’s dead. It would have its quiet parts and its plaques but ultimately its power would come from being a place for people to be together, which is one thing COVID took from us all.

This made me think of the 9/11 West Village memorial--a fence filled with tiles https://gothamtogo.com/revisiting-9-11-tiles-for-america-a-memorial-in-greenwich-village/.

A moving post.

How might we help actualize your Covid memorial vision?