What To Do With LA

Surveying the conversation around rebuilding a huge swath of America's 2nd largest city.

In 1666 flames engulfed central London, torching the Medieval city inside the Roman Wall, melting the lead roof of St Paul’s Cathedral, and spreading far enough west to threaten the palace at Whitehall. Once it was over, the architect Christopher Wren presented a plan to rebuild the smoldering city with grand avenues and a grid system replacing its jumble of medieval streets. I learned about Wren’s plan from a red-faced young man in a three-piece suit while we sat next to each other at a pub. He went on about “how much better” London would be if people had listened to “Sir” Christopher Wren, rivaling Paris and Rome in Baroque elegance. Someone I was with would later describe this guy as “a posh c**t,” but he got me curious enough that I looked up the fire and the plan in Peter Ackroyd’s entertaining book London: The Biography.

Wren was steeped in Renaissance architecture and his plan featured diagonal streets radiating from a series of piazzas and a monumental axis centering on a rebuilt St Paul’s. Despite widespread admiration for Wren and the support of officials, the plan never got off the ground for one predictable reason: The city's landowners weren’t exactly jumping to redraw their property lines or alter their holdings to allow a dramatic reimagining of the city. Officials became nervous that negotiations would delay rebuilding and people would quickly move elsewhere, hollowing out London permanently. The invisible lines of ownership, and the urgency of thousands of homeless people, made it so London was rebuilt largely along the same lines that had existed for hundreds of years, only this time with a lot more brick than wood.

I’ve been thinking about the Great Fire of London as we watch the slow-motion tragedy happening in the Los Angeles area. The various fires are the greatest destruction of an American metro area since Hurricane Katrina and the first I’ve experienced since entering the planning field. While the fires are still going, there is already talk of how to rebuild.

First, a bit of scale. Cal Fires says that roughly 57,000 acres have burned, about 90 square miles of land. If you superimposed the Palisades fire (only one of the several) over Brooklyn it would look like this.

Over sixteen thousand structures have burned, yes a lot of it homes in wealthy places like Pacific Palisades (controversial opinion but I think it’s sad when these people’s homes burn down too), but also nearly the entire middle-class enclave of Altadena. Smoke and ash have made neighborhoods difficult to live in even outside the flame’s direct reach. 150,000 people have been displaced or made homeless, and dozens have died. Billions of dollars of damage have been done, and the loss of property and income tax revenue will have a knock-on effect on the City for years to come. The more immediate costs to individuals will come from rebuilding with scant insurance support, and the loss of thousands of jobs, many held by immigrants. UCLA estimates that over 35,000 jobs held by Latinos across fire-impacted areas were at risk of permanently disappearing. By the time I publish this all these numbers will have increased, and numbers can obscure the zoomed-in impact of what’s been lost — places with deep history, many memories, and an only-in-LA charm: First and foremost people’s longtime homes, but also cherished roadside diners, art collections, architectural gems, churches, synagogues, and the Altadena Bunny Museum to name a few.

A Different City

The gut reaction of many architects, planners, and advocates, has been to push for a rebuilding effort that corrects the vices of LA’s urbanism - sprawl, low density, and dependence on cars. New York Mag quoted Marissa Christiansen, the executive director of the Climate and Wildfire Institute:

The city has an unprecedented opportunity to rebuild in a more resilient manner with denser urban housing and wide firebreaks abutting the mountains. “I do not think we should be building back in the same way and with the same footprint we did previously,” she said. “I think what we can learn here is that we are guests in this landscape.”

Writing for the journal Vital City, the architect Vishaan Chakrabarti was more explicit.

“Perhaps progressive residents could choose to replace 10,000 increasingly uninsurable single-family home sites, now reduced to deeply felt scars amidst trees and highways, with 100 new fire-resilient apartment buildings amidst parks and subways, all in the hopes of creating tougher, taller communities with smaller carbon footprints.”

I understand reactions like this. LA should retreat from its fire-prone hills into a less sprawling footprint. But these visions are challenged by two things. The first is weak governance. Any coordinated effort to drastically remake North LA will run into the same force that defeated Wren’s plan: Property owners who have just lost everything and simply want to go back to what they had, and a government incentivized to encourage quick rebuilding to keep people from permanently leaving. Governor Gavin Newsom made a show of suspending the lengthy environmental review process for new building projects in fire-affected areas (Although these rules were already suspended for single-family homes and in coastal areas impacted by disasters). Mayor Karen Bass announced measures to quicken permitting and cut red tape. There seems to be little appetite for a slow and considered rebuilding, and maybe that makes sense when so many people are homeless right now. LA’s tangle of jurisdictions will also limit any bold rebuilding vision. We think of LA as America’s second-largest city but really it’s a patchwork of jurisdictions. The City of LA is one of 88 municipalities in LA County. Fire doesn’t care about these boundaries, even one of these 88 governments dragging its feet or going its own way threatens the entire region. Even if it wanted to, the City probably lacks the funding or the power to impose a top-down rebuilding project.

The second obstacle is willpower. Planners like to criticize LA for being a confusing low-density sprawl, ignoring the fact that this is precisely why so many people like the city in the first place. The aspiration that you can live in the hills on a tree-lined street and be a short ride away from the delights of a major city is fundamental to LA’s appeal. Nor are these places the rootless spread of McMansions that many outsiders imagine. These are neighborhoods that have existed for a hundred years with specific histories, vernacular designs, and generations of appeal. The urge to rebuild in the style of what was lost will be much stronger than when a Florida condo development slides into the ocean after a hurricane. Chakrabarti’s idea of “100 new apartment buildings,” may be challenging from a feasibility standpoint, but the bigger question is does anyone who lives there actually want that? (I’ll add that while I’m skeptical of that sentence, Chakrabarti’s piece is worth a read, and I have a lot of admiration for his practice, PAU)

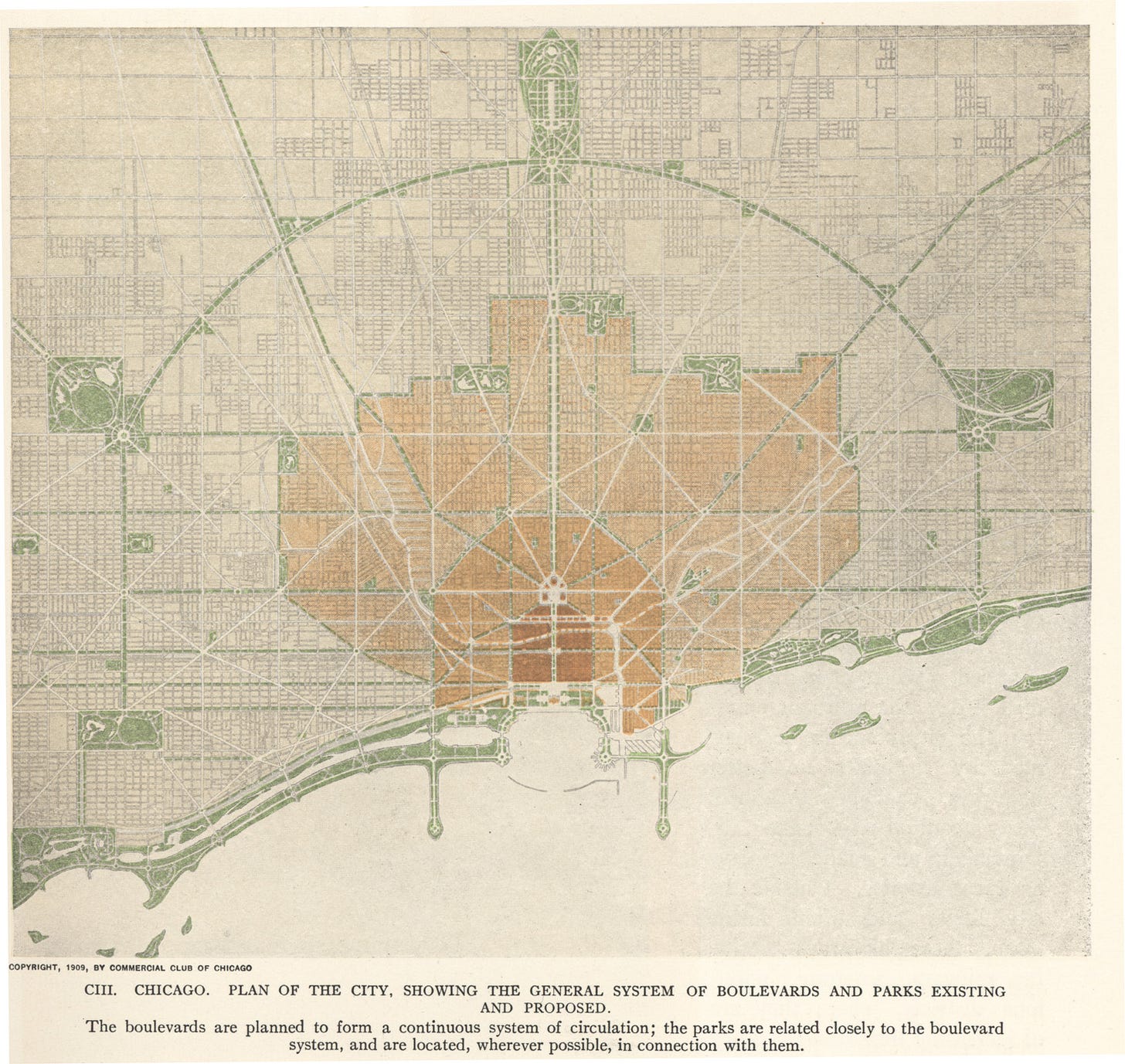

This is not to say that a bold, unapologetically urban reimagining of North LA shouldn’t be put forward. A plan doesn’t have to be fully instituted to make an impact, it just has to expand people’s sense of what is possible. Chicago was burned to the ground in the late 1800’s, and in 1909 the architect Daniel Burnham put forward a radical city-wide masterplan for a “Paris on the Prarie.” Burnham’s plan was never adopted, but many of its ideas - most notably the creation of a network of parks along Lake Michigan, won enough powerful fans that it subtly guided the city’s development for decades. A few days ago Newsome announced $100 million dollars had been donated by the philanthropy group LA Rises to fund the creation of recovery plans and rebuilding proposals. There should be a robust debate about what future-LA looks like and bold plans can provide the spark.

A Differently Shaped City

If a Wren or Burnham-style plan is unlikely to be adopted there is still plenty LA can do to move itself out of harm’s way. Part of the tragedy is that, while the fires are unprecedented, the warning signs were fairly obvious in hindsight. The US Forest Service included Pacific Palisades and Altadena in its 2020 assessment of fire-prone areas. As far back as 2005, officials were raising alarm at the 5 million California homes in the Wildlife Urban Interface (WUI) zone, "the zone of transition between unoccupied land and human development…where structures…intermingle with undeveloped wildland or vegetative fuels." By 2024 this number had only increased, and although the state began requiring stringent fireproofing in these areas, it did nothing to require the retrofitting of existing structures. The city’s development pattern combined with the increasing intensity of drought and the Santa Ana Winds was always a recipe for disaster.

LA will have to get serious about limiting construction in the WUI. A roundtable of the California chapter of the American Planning Association discussed the creation of a stricter “buffer zone” between the city and the surrounding forests. If the city cuts itself off from the mountains and canyons this will mean embracing growth in other ways. 78% of the land in LA County is zoned for single-family homes - an insane amount even if I concede that single-family homes are a huge part of the city’s appeal. It’s no surprise that the city has sprawled into fire-prone wildlands when building up is almost impossible. It may seem counter-intuitive that clustering more people together is a way to prevent devastating fire, but densifying away from fire-prone areas will be the only option unless the city wants to keep developing headlong into the tinder or stop growing altogether.

Displaced fire victims have already been moving into people’s backyard sheds, also known as granny flats or accessory dwelling units (ADUs). California used to have notoriously strict standards preventing owners from building guest houses or ADUs on their property. The relaxing of these standards in 2016 led to an explosion in ADU construction, and that change is paying off right now. Not every way of densifying is an apartment tower. Planners call development in underutilized land “infill development,” and LA with its huge single-family lot sizes and liminal spaces is a prime place for more of this.

Better building

Much attention has been paid to individual homes that survived the fires and the design choices about materials, planting, and layouts that made these properties more difficult to burn. Many of these measures should (and probably will) become requirements. California already has “defensible space” rules that require homeowners to clear brush, clean gutters, and trim trees around their property to limit the ability of embers to leap from burning vegetation to homes.

wrote an excellent piece on why building code reform may be the most meaningful thing LA can do in the fire’s wake. Past efforts to extend fire safety rules have been held up by, among other things, the high cost of fireproofing older structures and homeowners’ opposition to removing flowers, bushes, and other plantings from around their homes.I think it’s safe to say that opposing fire codes on gardening principles will be more difficult now that people have lived through the past month. Lind argues that money should go towards grant and loan programs that help homeowners rebuild to a higher fire safety standard, or retrofit their existing structures. She points to Florida as a state where people continue to stubbornly build themselves into the path of hurricanes and rising sea levels. Unable and unwilling to limit this pattern, Florida has instead gone all out on hurricane-proofing itself with better building codes and has been relatively successful with it. These changes have been state-wide, a local municipality can’t simply opt-out. A change in building standards has followed every great urban fire in recent history, from London to Chicago, and there is no reason LA should be different.

This is the end… of something

The beginning of the end can be hard to see. LA’s population has been declining for years. Its inability to build new housing or deal with a chronic homeless population coupled with an ever-rising cost of living and a declining entertainment industry has scrambled people’s calculus for living there. The recent fires could be the punctuation mark on a period of decline. I don’t want to sound overly dramatic, but I think we are seeing the end of a specific version of LA. But great cities have their own inertia. LA is too culturally prominent, too well placed, and too beautiful to stay down forever. People will still write songs about the city. Last night the Lakers destroyed my Knicks and traded for Luka Dončić. This sounds beside the point, but it’s not. The strongest force for rebuilding LA could be its own sense of self-importance and the idea that it is too cool and fundamental to America not to rebuild. If the house in the hills is no longer an innocent aspiration then I do not doubt that people will come up with a new LA dream to aspire to. People will invent new reasons to be there, and hopefully, planners and officials help make sure those aspirations live in better harmony with nature and our changing climate.

All my in-laws live in LA. Not in the hills or near the coast, but mainly in the flat, cookie-cutter, postwar developments: no beauty, but not the same fire danger either. What if these more fireproof areas suddenly became more desirable?--hard to imagine from a class point of view, for sure. In the meantime, City of Los Angeles, please listen to Matt Choi's ideas here!

Planning and building innovation is crucial; if only it were balanced with real energy and policy to stem the terrible tide of climate change.