There are a lot of pictures in this, so best to view in the app or on the website as the email will be cut off due to length.

Towards the end of high school, a book swept across my friend's parents' living rooms and coffee tables. Certain cultural artifacts moved through these living rooms in waves, like a rabbit wine opener or Six-Feet-Under DVD box sets. They were rarely used but nice to look at. The book was Manahatta by Eric Sanderson, a book I’ve never read but whose cover I can still see clearly — Manhattan Island gleaming with steel and concrete on one side and in its long-lost natural condition on the other.

There are few spots where Manhattan’s original nature peeks through. A 30-foot-tall chunk of actual Manhattan bedrock with apartment buildings for neighbors, or Inwood Hill Park, are just a handful of places you can squint and see what the island looked like for thousands of years before European settlement.

Nowhere is this more evident than at the water’s edge. Rivers and bays are where cities definitively meet nature, but you can circumvent Manhattan, and almost nowhere will you see the original condition of the shore. These would have once been a mix of sandy shoals and saltwater marshes, but today the water edge is mostly made of bulkheads. I took the below picture of a crumbling bulkhead in Red Hook. You can see the steel bulkhead wall, filled in on the landside with crushed rock and then paved over to create a smooth grade, which is now eroding.

In urban design parlance this is known as a “hard edge” - a solidified boundary between water and land rendered in concrete, stone, and metal. Hard edges are easy to walk on, drive over, and build on top of. They turn the shoreline into developable land.

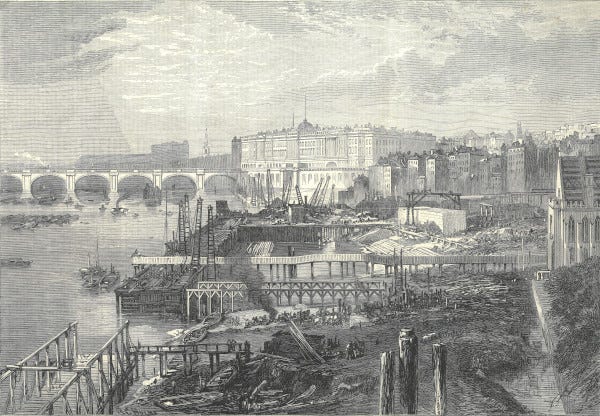

You can walk for miles along the Seine, the Chicago River, the Cuyahoga, or the Thames with nothing but pavement under your feet, the only patch of nature the water itself. Hardening a river edge was historically a way to tame it. Rivers like the Potomac or Thames that are now defined lines would have once been vast fuzzy stretches of marsh and swamp with veins of creeks shooting into the surrounding land. They would have swelled with the daily tides and flooded the surrounding region seasonally. Not exactly ideal for building or navigating. Generations of land reclamation and “embanking” have turned many urban rivers into inert canals. The below engraving shows the construction of the Victoria Embankment on the Thames. If you look closely on the right, you can see the slope of the actual shoreline being built over with the right angle of the embankment itself.

The medium term impact of these projects was to insulate cities from the unpredictability of rivers and create navigable channels for goods and people. If you detect a tinge of sadness in the way I describe the loss of nature to embankments, it’s countered by the fact that a lot of them have ended up being really, really nice places. The Chicago River is one of the most manipulated bodies of water in the world, deeply unnatural to the point of basically being a canal. And yet, it’s beautiful — A canyon that cuts through the city fronted by architectural gems. Even as a New Yorker with an inate sense of urban superiority, floating down the river towards Lake Michigan on the obligatory Chicago Architecture Tour gave the sense that I was in a true world capital

Successive investments in the public spaces along the river have made it an attractive place to linger. The water here feels tantalizingly close and accessible. A hard edge tends to cut off the water from access, but steps and stone slopes bring back some balance. In India, a Ghat refers to a set of steps that descend into the water to facilitate wading, bathing, and the easy movement of people on and off boats. Ghats have become something of an urban design trend. The landscape architecture firm Sasaki integrated a series of steps and slopes into the redesign of the Chicago Riverwalk to great effect. People sit and laze, kids go right up to the edges and even paw at the water itself.

All this would have been unimaginable a century ago when these waterways were industrial corridors, but as the economic importance of rivers has declined their edges are allowed to fill up with promenades and public spaces. New York City has created a specialized zoning class for its 520 miles of largely post-industrial coast. The Comprehensive Waterfront Plan asks that new waterfront development go hand in hand with new public space and access points for boating, transit, and recreation.

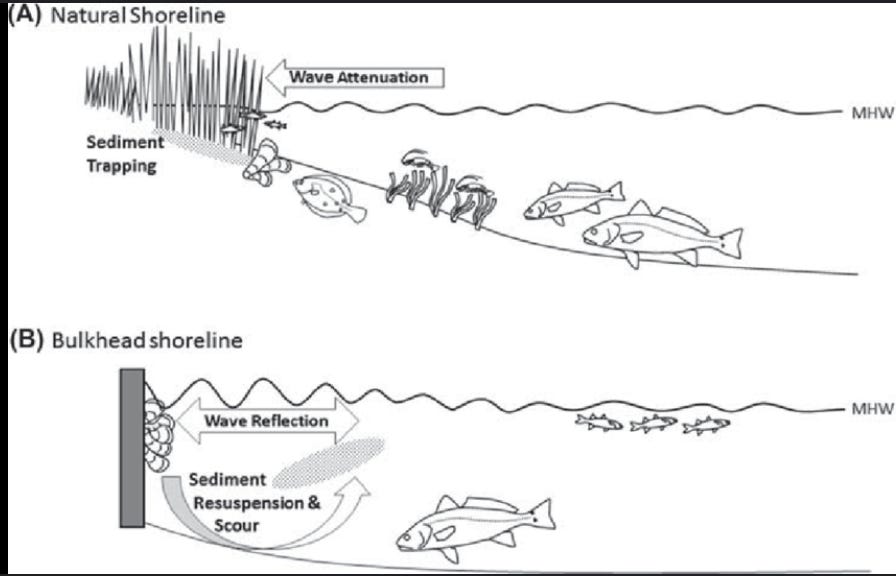

The elephant in the room is rising water levels as climate change reveals the flaws in building hardened waterfronts. Water pushing up against a steel bulkhead has only one place to go, up and over. During Hurricane Sandy, the flooded area of Manhattan roughly matched the historic contours of the shore — the river simply returned to its previous boundaries before all the piers, walkways, and land reclamation. The new trend in urban rivers is “soft edges” that restore or approximate the natural shoreline. A wave will crash violently and then reflect against a wall, but will peter out along a slope.

Hunters Point Park in Queens and Brooklyn Bridge Park are two notable new-ish projects that involved adding manmade wetlands and intertidal zones back to the shore. These don’t just break up storm surge, the flood-tolerant landscapes can actually act as sponges during high tides.

These places also restore shallow water habitat, inviting a vast class of animal and plant life back that had almost been eliminated from our cities. Juvenile fish hide in reeds where invertebrates and shellfish have taken root and birds return to the shoreline to eat it all up. The City has been looking favorably upon projects that restore these coastal conditions and it’s not a stretch to think that elements of softened shorelines may soon become a requirement of waterfront development. A huge apartment tower in Williamsburg designed by Bjarke Ingels was granted permission for a controversial rezoning partially on the back of what it offered to the shoreline. The project, known as River Ring, is being built on the site of a former fuel oil storage facility on the East River. The water-side fuel tanks and paving are to be removed to make way for an actual sandy beach and tidal marsh — remediation and amenity combined into one.

The landscape architecture firm Field Operations proposed two speculative schemes for the banks of the Potomac River in Washington D.C. that took soft edges to an almost fantastical extreme. In one scenario called “Island Archipelago,” the tidal basin of the Potomac is allowed to flood again. Earthworks and marshes are strategically placed around the national monuments to turn the National Mall into an archipelago of Cherry Trees.

In an even more dramatic proposal called “Curate Entropy” the Potomac is allowed to go completely where it wants, eventually flooding the National Mall including the statues and memorials, which would be made accessible for viewing via elevated walkways. The edge between river and city is completely erased.

The irony that we are ripping out the concrete and steel to meticulously remake the exact type of landscape we destroyed is obvious. Nick Paumgarten had a recent story in The New Yorker about a group of Germans trying to teach a species of bird, the Bald Ibis, how to migrate across Europe. This particular species had been native to the continent before being hunted to extinction, and researchers have been trying to reintroduce them to Europe with birds taken from remaining populations in Turkey and North Africa. Paumgarten describes the researcher’s efforts to restore the bird’s migration patterns, which involve tricking them into thinking one of the researchers is their mother, mounting this fake mother onto a specialized plane and physically leading them over the Alps and Pyrenees in a real life version of Fly Away Home. This particular quote stuck with me:

Our devastation of nature is so deep and vast that to reverse its effects, on any front, often entails efforts that are so painstaking and quixotic as to border on the ridiculous.

I took the ferry to Hunter’s Point park last week, where even though it’s just starting to get warm, the grasses in the marsh are still a straw color and everything is leafless and dead. Coke cans and bags were strewn about the tide pools and two stray cats were having a staredown on the bank. But a pair of ducks bobbed in and out of the reeds, and occasionally one would dive under and come up chattering its beak. There is something to eat down there. The UN stood in the background across the river. with the Manhattan grid arrayed around it. The scene left little doubt that you were in New York City, but now the ducks were back.

![Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City [Book] Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!WZa4!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe2b5a9ad-5157-4e19-886c-5a8567793e04_818x1073.jpeg)

I am here for any and all Fly Away Home references

I revel in your knowledge of cities worldwide, and enjoy your travels, local and global, vicariously. As a kid in New York in the 70s I couldn't believe how poorly Manhattan used its waterfront—my father used to park his car long-term in the cheap parking lots next to the East River (already ruined by Robert Moses’s FDR Drive). More recently, New York has been realizing the value of city waterfront (Battery Park City, et al.)...just in time for the rising waters of climate change. Thanks for this gorgeous post.