A lot of photos in this one, so the email will be chopped off. Read on the App or at the website for the best experience.

Sometimes I feel like NYC is in denial that it is… hot as shit. Not in a Do The Right Thing heatwave way, but in a it’s just like this now kind of way. The local government’s primary response to rising average temperatures has been to establish a network of cooling centers in libraries, schools, and senior centers where people without air conditioning can go to escape heat waves. The centers are activated when the forecast hits 100 degrees or when there are consecutive forecasts above 95 degrees. While they do a lot of good, they represent a mindset in which extreme heat is an occasional emergency rather than a constant part of life. Sometime around 2020, depending on which official body you consult, New York City shifted from a “continental climate” to a “subtropical climate.” A subtropical climate isn’t something that turns on and off. In the early 2000s it was popular to imagine sea level rise as the main danger of climate change, but constant, high heat has quickly proven to be the deadliest result. So it was interesting in the last few weeks to travel to three cities, Seoul, Tokyo, and Kyoto, that have been dealing with persistent heat for a long time.

When I left New York for Asia in June, it was a cool 98 degrees. When I arrived in Seoul, it was a relatively cool 88 degrees, but with the type of humidity that sucks clothes against your body. Seoul was entirely destroyed by the Korean War and had to be quickly rebuilt to house a massive refugee population, and later to fuel exploding industrial growth. It was built to be car-dependent, and its tree-covered mountains and hills were stripped by bombs and later to be used as fuel. Much of the thrust of Seoul’s urban planning since the turn of the century has been smoothing out the rougher edges of these periods. The city is vastly more walkable than when I visited 17 years ago, with wider, tree-planted sidewalks, little plazas, and new parks. Still, it has awful traffic, and pedestrians have lengthy waits at crosswalks to traverse wide roads. So these wide umbrellas that shaded corners were one of the first things that jumped out at me.

The government began installing the umbrellas in 2015 to shade people waiting to cross, and there are now about 6000 of them spread through the city. It’s a very simple and low-tech solution, and if you’re walking around in the middle of the day, they do make a difference in your comfort. Several outlets I read noted the material used to make the umbrellas has recently been improved to up the UV protection, which makes sense in the most skincare-obsessed country on Earth.

Bus stops also had these deployable shade canopies, which had arrival times integrated into their screens.

In New York, there has been a longstanding effort to increase the city’s shade canopy, but this has been almost entirely executed through tree planting, which is expensive, and it takes a new tree many years before it grows to the point of offering shade. Something like these umbrellas would be fairly easy to add to the NYC toolkit, which already has posts at the curb corners for street signs and crossing signals.

Another cooling feature I noticed was the use of linear water features built into the environment and a lax approach to playing around in them.

Fountains are more than decorative. When water evaporates, it absorbs heat from the air, and a strategically placed water feature can cool the surrounding area by several degrees. The below water feature in Seoul Forest Park — a little more than a drainage canal— had been charmingly accented with stones and inbuilt benches so people could sit and dip their feet in.

I was reminded of this villa I saw in Pompeii, where a dining area was arrayed around a water spout in the wall so that diners would be cooled by the flowing water. These ideas are not novel; they have been deployed since antiquity.

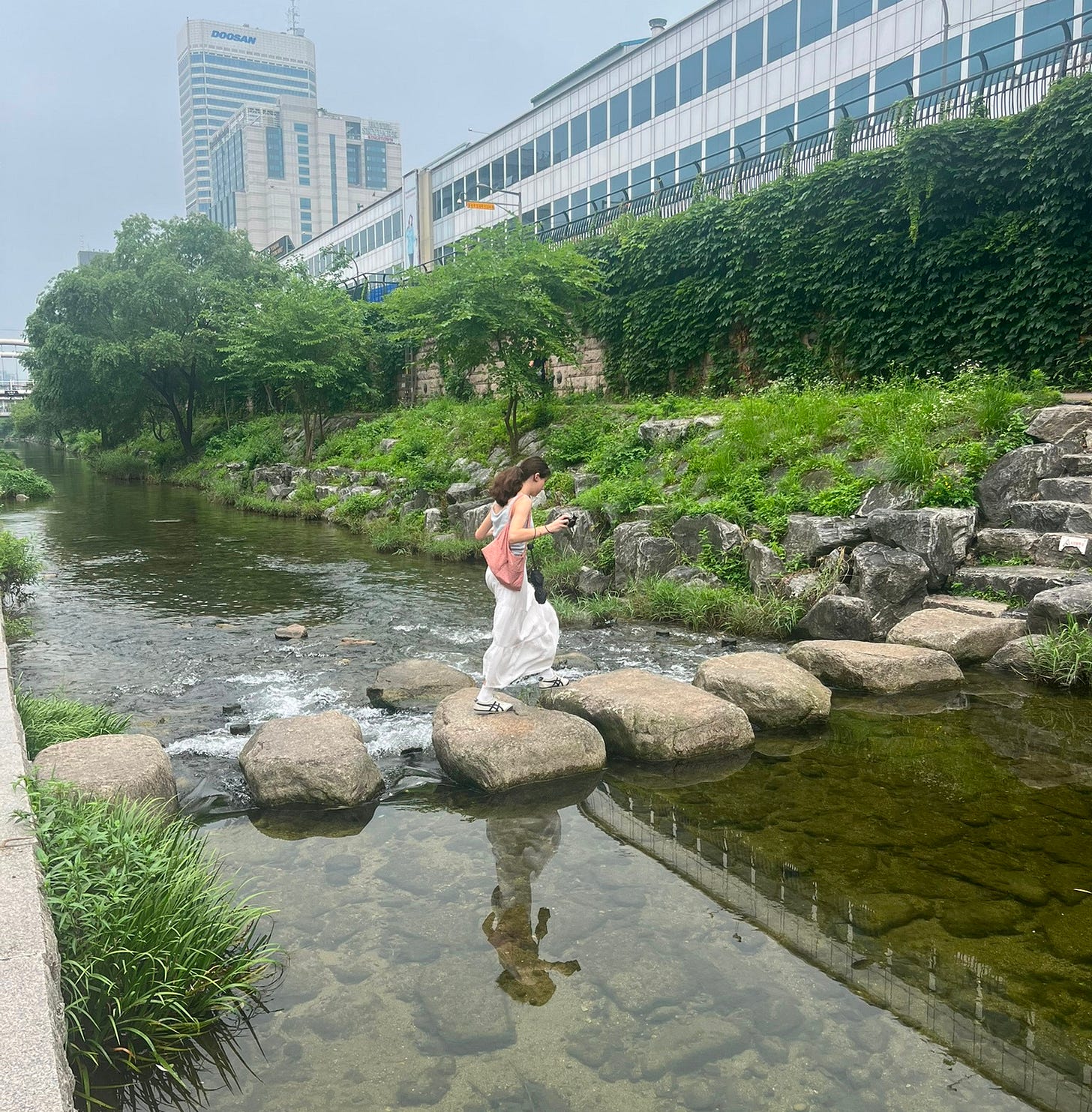

Cheonggyecheon, a natural stream which was almost completely filled in for a freeway postwar and uncovered in 2003, applies this principle at a massive scale. Temperatures in the streets along the stream are about 3 degrees Celsius cooler than the city average.

Unrelated to cooling, this was just an amazing project to see since it was in its infancy the last time I was in the city. I was particularly smitten by the regular stone crossings people could hop over; this would be a liability nightmare in the US and probably never happen.

Projects like Cheonggyecheon are part of a concerted effort by the metropolitan government to break up the amount of heat-retaining surface concrete in the City. One of the spectacular things about Seoul is that it has several large mountains within its boundaries, which have numerous streams and springs flowing from their slopes into the Han River. Over the years, many of these have been channelized or filled in completely. In 2022, Mayor Oh Se-hoon launched 4 pilot programs to restore natural conditions at streams around the city, including Dorimcheon stream pictured below. This year, the City launched its Stream Renaissance project to restore 75 streams by 2030.

There is also a decent amount of personal/micro cooling. Each police man guarding the US Embassy downtown stood under an identical deployable umbrella. Many of the parking attendants or doormen I saw outside large buildings had an umbrella and a mobile AC unit blowing cool air over them. In Japan, I noticed many of the outdoor train stations had small air-conditioned waiting rooms on the platforms where riders could cluster. I wonder if the urban future builds on this, kiosks or little cooled stations where people who need to work outside can stand or at least take a break. Certainly, there has to be a more energy-efficient solution than a mobile AC blowing cool air into the 90-degree day.

This isn’t exactly about urban planning, but everyone also had these little battery-powered handheld fans. Unlike my Korean father, who seems to share his countrymen’s propensity to sweat minimally, I am both hairy and sweaty, and soon I was following my family around with this thing firmly aimed at my face… and up my shirt… and down my neck, pretty much all the time.

I have been to the American Southwest. I have been in Southern Europe during the summer and on the Gulf Coast of Florida. I have even waited for the A train at West 4th Street on a 100-degree day, but I have never been anywhere as hot as Kyoto last week. My first step off the train released me into an oven that even the strategically placed platform misters could not help. In Japan, I had to take my personal cooling to the next, embarrassing level, and buy one of the fan coats I saw all the gardeners/construction workers/traffic cops wear that creates a little microclimate against your body.

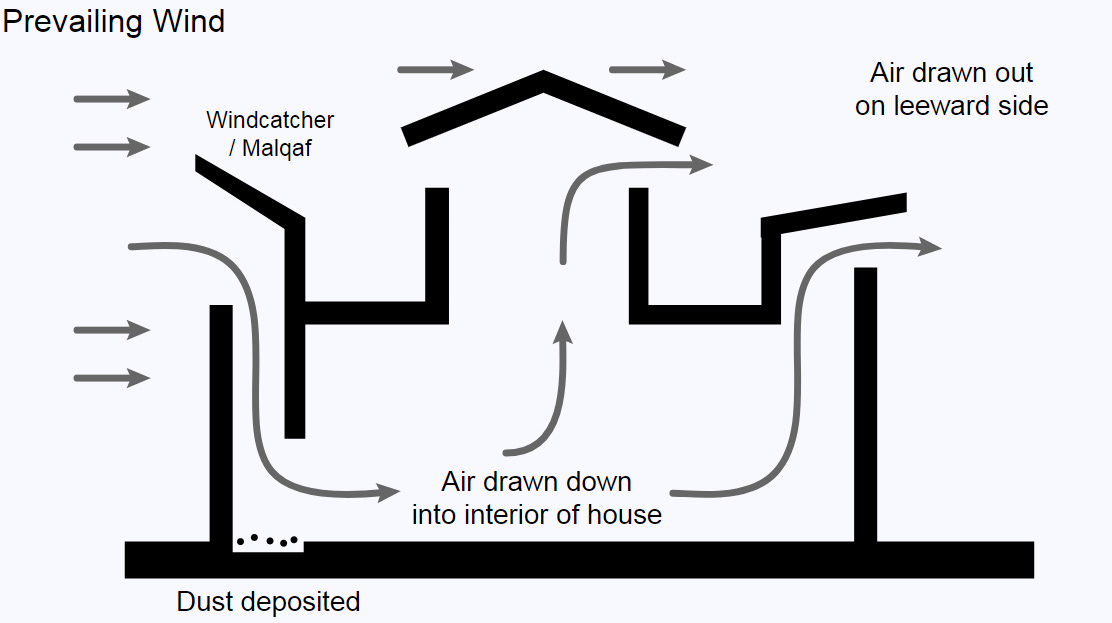

Everything I’ve described so far can be roughly divided into two types of cooling, passive and active. Passive cooling includes things like shade and using materials that don’t absorb heat. Active cooling includes powered sources of cooling, like fans and AC. In an era before air-conditioning or electricity, we used to work very hard to build cities in hot climates that harnessed passive cooling. When I worked on projects in the Middle East, I was constantly impressed by urban-scale passive cooling methods from the region’s vernacular architecture. At the most basic level, cities were built with narrow streets, which guaranteed shade on at least one side of the street for most of the day. Homes clustered around courtyards that regulated airflow. On the more spectacular side were things like wind towers, which draw cool breezes from the air down into the interiors of large buildings, sometimes passing it over water to create an evaporative cooling system that expels hot air out the other side.

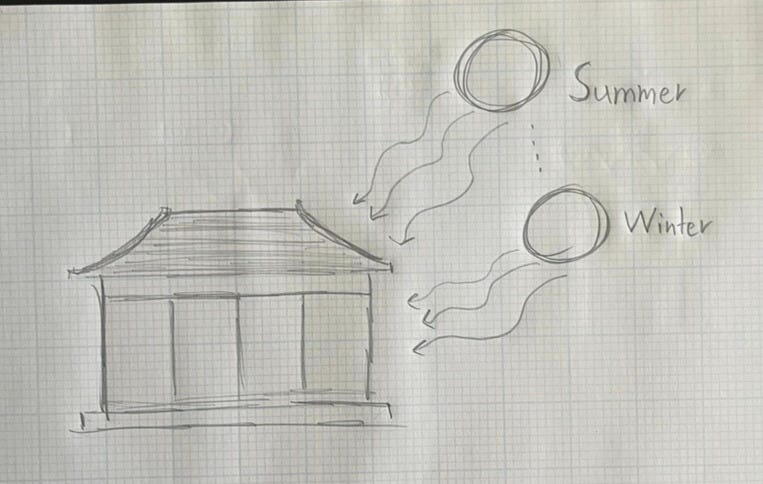

In Seoul, I visited one of the few remaining Hanok areas, small neighborhoods where it is still possible to see traditional Korean homes. The slope of the tile roofs here is carefully calibrated to block the sun when it is high in the sky during the summer months, and let it in when it is lower in the winter.

Both Japanese and Korean traditional buildings use systems of sliding doors and courtyards to regulate breezes throughout interiors, and rice paper, which blocks light but lets in air. Both Seoul and Tokyo are plentiful with covered arcades and domed markets that block the sun and rain. It is not backwards to look at these low-tech, sometimes ancient solutions. Cities in Asia and beyond are implementing robust public realm heat-mitigation with these cheap, time-tested methods. I would love to see building code reform in NYC that simplifies the process for street coverings, awnings, and arcades.

Even before the Trump administration began to dismantle our Federal disaster response apparatus, there was almost no National funding source for heat mitigation. Climate change disaster response, like the National Flood Insurance Program and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, was aimed at more spectacular, but overall less deadly, instances of flooding. Heat mitigation is largely privatized, contingent on your ability to afford an air conditioner and the energy used to run it. But it’s hard to do nothing when the heat is so obvious. Building code requirements are getting serious about green roofs and permeable surfaces. The government and independent researchers in New York City are finally starting to compile detailed heat maps of the city, which I hope will lead to comprehensive plans to cool the hottest residential neighborhoods. Perhaps the socialist republic of Zohran Mamdani will go on an umbrella spree.

Seoul & Japan stuff not about cooling

In many neighborhoods of the cities I went to, there is almost no delineation between pedestrian, car, or bike space. In many areas, there is no sidewalk at all. In the Euljiro and Seongsu neighborhoods of Seoul, vans and taxis crept slowly through hordes of shoppers and diners. In Tokyo and Kyoto, where there is a robust commuter cycling culture and pretty much zero dedicated bike lanes, unhelmeted Japanese bikers weaved deftly through crowds of walkers.

The dogma in American planning is a strict separation of travel modes — sidewalks for people, bike lanes for bikes, roads for cars, all as physically separate as possible. There is an alternative school of thought commonly associated with the Dutch but clearly embraced in Korea and Japan that the simplest way to pedestrianize a street is to remove separation, not create it. The logic is that drivers and cyclists do not seek to kill people (this would be a shocking assumption for many New Yorkers) and that on a busy street without the aid of lanes, they will be forced to pay attention and naturally moderate their speed. I’d be nervous to try this in the aggressive vehicle culture of America, but having experienced it for several weeks, there is clearly a lot of truth to the idea.

Both Korea and Japan put us absolutely to shame in terms of accessibility. There are plenty of public elevators, and almost every street has these textured yellow lanes meant to guide blind people around.

Japanese subway and commuter stations are also incredible for the amount of infill and retail that have been incorporated into them. These are wonderfully covered in Jorge Almazan’s Emergent Tokyo. Rail viaducts, which often break the continuity of city streets, have essentially become market hubs for many surrounding neighborhoods, like the one below in Koenji.

As I experienced while living in London and enjoying several businesses that occupied railway arches, the slightly subpar conditions allow a diverse cross-section of businesses to exist that might not be able to pay rent elsewhere. I was happy to visit this vintage toy shop under a railroad track that my friend Griffin recommended.

These small business clusters, as well as the plentiful public markets and arcades in both Korea and Japan, are in stark contrast to the gleaming malls that also dot each city. In Seoul, it was possible to walk two blocks from the Shinsegae Department store, 14 floors of globalized luxury retail, to the Dongdaemun market and haggle with women over Ginseng wrapped in paper towels or eat a rice cake with a toothpick plucked from a bubbly cauldron. I may write something about the retail landscapes in both cities, but needless to say, I was surprised that in-person shopping of all sorts is so robust despite these countries, and Korea in particular, being very online.

Brilliant article

I forwarded to friends.

Loving this. I write about China Cities, so this is amazing I guess to see the Korean parallels