All my life I’ve had three recurring dreams. My anxiety dream: I’m graduating high school when I realize I forgot to take a class and have to make it up in two weeks. My flying dream: I jump up in the air, make an approximation of the dolphin kick, and slowly begin to float away like a balloon (A deeply un-cool flying dream). The third dream changes but the location is always the same. I’m in a city on a big river with incredibly steep banks. The streets are narrow and the buildings are generally dense blocks of federal-style rowhouses and brownstones— Brooklyn Heights but on a cliff spread along a river. What happens here changes, sometimes I’m just wandering around. At least once I was running away from a zombie hoard. There is always a lot of going up and down hills. I think there is a weird human urge to be on top of something tall. Maybe it’s a vestige of our primate past — climbing a tree to look out over the African plains for approaching predators. Frank Sinatra croons that he wants to be “king of the hill, top of the heap,” in New York, New York. Despite living in a pretty flat place, I’ve always been drawn to cities with dramatic changes in elevation.

My East Coast cynicism about San Fransisco faded away after viewing the city during a foggy sunset. Hilly neighborhoods and skyscrapers broke the fluffy blanket of fog bathed entirely in golden sunlight. I love the winding staircases, Miradouros (viewpoints), and diagonally slanted trolleys in Lisbon, a city where everywhere you look there is a castle or church dome perched on a distant hill.

Seoul is a city that has essentially filled in the lower reaches and valleys between several mountains. At night the mountains form huge dark patches across the lit-up skyline. For some reason, my Youtube feed has been serving me videos of Chongqing - a city essentially built into a canyon on the Yangtze River. The city’s downtown terraces towards the waterfront, making the skyscrapers built at higher rungs look even taller than they actually are.

Living at elevation is a privilege and a burden. Historically, living up high meant fresh air, nice views, a defensible position, and no one’s shit could flow downhill into your neighborhood. The Emporer’s palace sprawls across the Palatine Hill in Rome. In Hong Kong, Victoria Peak sits over a thousand feet above sea level and hosts the city’s most exclusive residential area. Mansions nestled into the leafy slopes with expansive views over the city’s downtown sell for tens of millions of dollars. But in Medellin, Colombia it’s the exact opposite. The steep hills surrounding the city host aluminum-roofed informal settlements cut off from the city’s central business district for years until the government built a system of cable cars to hoist commuters up and down the terrain. A Lisbon resident once joked to me that when you have a baby you have to move to one of the city’s flatter peripheral neighborhoods unless you want to lug a stroller up and down the slippery tiled streets. The price of living in the hilly, picturesque old town is a lot of extra leg work. The Danish urban design and planning consultant Gehl was hired to study food access in Lisbon’s hilly Ajuda neighborhood. 55% of residents reported that elevation was a major limiting factor in their access to fresh groceries. Gehl recommended a number of initiatives, including clustering food distribution around bus stops and paying young people to deliver groceries to the elderly as ways to circumvent the climb.

These cases show how elevation can be an amenity, but in many ways is also a problem to solve. Dense cities so completley transform the land they’re built on that it’s easy to lose sight of their natural foundations - but a mountain is hard to flatten, and so topography is one of mother nature’s most stubborn influences. Stuck with their grade changes, cities have been coming up with ways to ease the climb for millenia. The winding switchback road and staircase are probably the two most common examples.

These are analog solutions. The ultimate hill-conquering techniques draw on external power, funicular railroads, or the afore-mentioned cable cars. Caracas and Medellin operate probably the two most robust urban gondola systems in the world, fully integrated into the municipal transit systems with linkages to bus and rail. These lines also link some of the city’s poorest hill neighborhoods to jobs and amenities downtown. I’m not afraid of heights, but photos of these systems make me slightly nauseous.

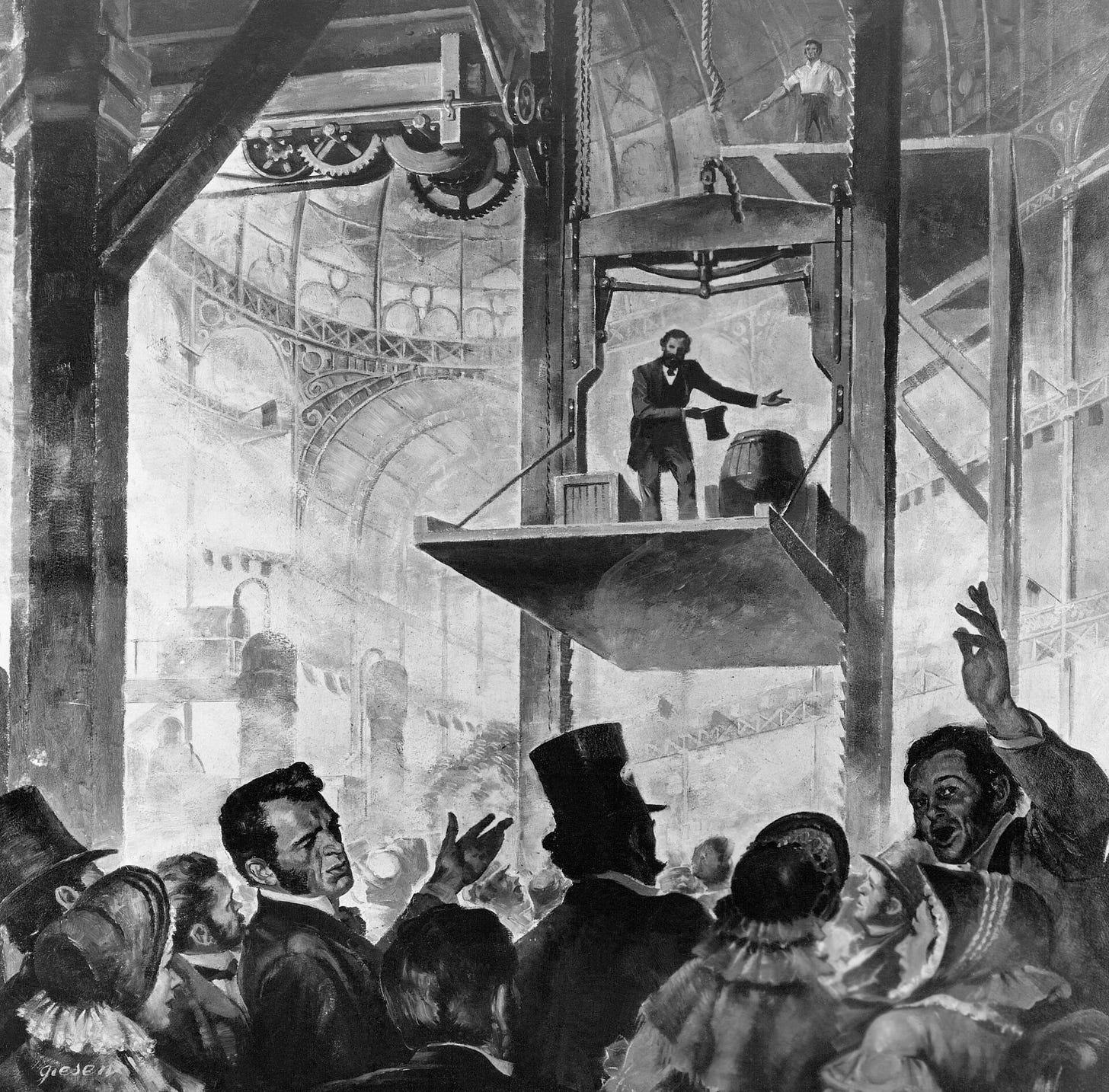

At a smaller scale is the good old fashioned elevator. Elisha Otis invented a lift with breaks that stopped it from freefalling if the power was cut or the hoisting cable broke. He demonstrated his “safety elevator” in 1854 by purposefully cutting the cable of his invention while standing on it. After that, the elevator spread widely.

As someone who lives in a skyscraper city, I often associate elevators with buildings, but in some cities they’re transportation. Returning to Lisbon, in 1902 the city inaugurated the Santa Justa Lift to connect downtown Lisbon to Carmo Square which stood on an adjacent hill. You can still buy a ticket and ride up the wrought-iron, neo-gothic elevator today.

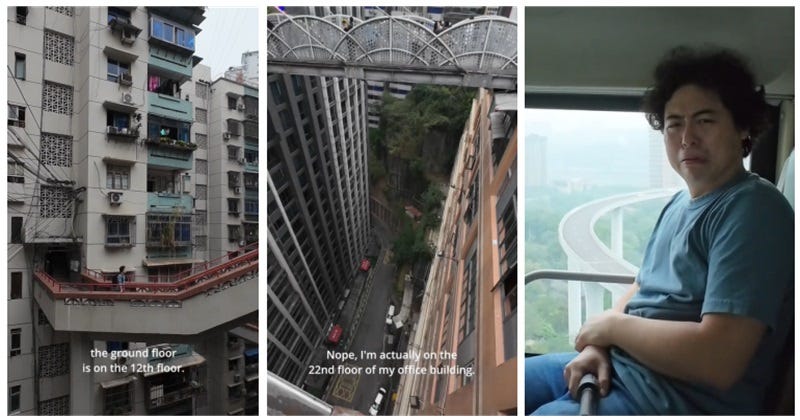

Chongqing may be the biggest modern city where commuting by elevator (and escalator) is really a way of life. The Kaixuan Road elevator moves about 14,000 people a day, and knowing the city’s network of public and semi-public elevators is a neccecity. I’ve become slightly obsessed by this Youtuber who lives in the city. His commute to work involves him losing hundreds of feet of elevation. He starts the day by descending a massive escalator to a subway which drops him off at a public square that is actually level with the top of his office building.

I could go on about the Archimedes Screw or the Acoma ladder or any of the dozens of other inventions that get goods and people up and down urban areas. It’s enough to make you wonder why we don’t just all live on flatland. Some studies suggest that rapid changes in elevation actually release dopamine, and looking at some of these cable cars is enough to quicken my heart rate. It’s probably not that complicated. I watched my friend’s baby, who can’t even walk yet, try to climb up a small ledge in the playground the other day while nearby a slightly older kid went down the slide headfirst. If you can turn elevated areas into usable space why not, it’s a little thrill being in these places even with their burdens. They call it “being on top” for a reason.

Freakin' fascinating! I'm also fascinated by the shifting history of height *inside.* Before elevators and air-conditioning, the higher floors of fancy buildings were the servant-quarters because it was so hot in the summer and so much work to climb up and down (and to haul firewood up the stairs for winter heating). I long ago lived in a top-floor apartment inside the red brick buildings on Washington Square North; these were once individual townhouses, later combined (behind the facade) into a single apartment building with elevators. The top floor, I noticed, had much lower ceilings than the other floors--to go with, I imagine, their undesirable placement up five flights. When I gaze at the Plaza Hotel on Fifth Avenue, I imagine (though I don't know for sure) that behind those many tiny windows embedded into the slanted roof once lay cramped, unpleasant spaces for the maids and butlers--despite the beautiful views over 19th-century Central Park.

I live in a small hilly city, you quickly learn the public access elevators that get you to where you want to go. That + e-bikes!