Street Eats Vol 3: Terroir de Brooklyn Queens Expressway

The third in my ongoing series of interviews and article on the intersection of food, drink, and planning.

For a short time, my family belonged to the Park Slope Food Co-Op, when it still had a whiff of hippie and was less a cluster-fuck of neighborhood politics. The food was great—Farm-fresh and at prices that competed with local chain supermarkets. I was too young to remember much, but I do remember being stunned when my dad brought home a chicken with the feet still on. Growing up in a city inspired a strong appetite. A place where 800 languages are spoken and most people have tiny useless kitchens is bound to be good for eating out. What the chicken feet revealed was my lack of exposure to ingredients and the system that cultivates them. Yes, chickens have feet. This is not unique to cities, you can go into pretty much any American grocery store and get asparagus out of season flown in from Peru and dinosaur-shaped chicken nuggets. In the two years between Super Size Me and the Omnivore’s Dilemma, it seemed like a food system revolution was underway in America and we would all eat seasonally and locally. For reasons outside the scope of this newsletter, that moment never really moved beyond a specific urban elite.

I thought about the chicken feet and my distance from food production the other day when I was catching up on The Neighborhoods, an incredible project by

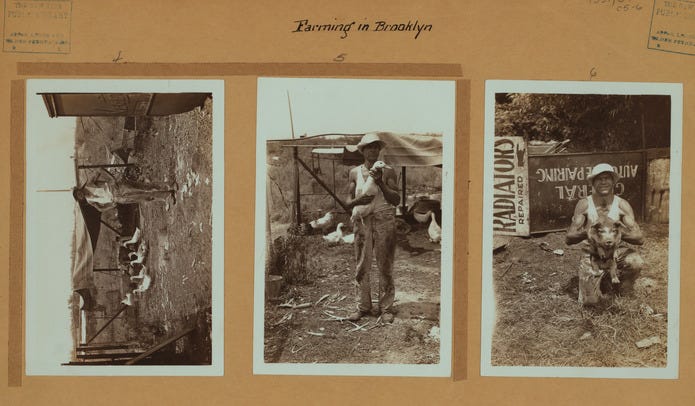

that I cannot recommend enough. Stephenson’s profile of the Soundview neighborhood of the Bronx had this striking picture of a family farming a plot of land along what is now Bruckner Boulevard.Within living memory, large farms operated inside city boundaries. This field belonged to a family who farmed the loamy soils of the Bronx up until the mid-1940s. My grandfather could have walked from his childhood home to functioning livestock farms in East New York. The picture below shows a farmer with his ducks and a pig just off Stanley Avenue.

According to a 2022 Dept of Agriculture census, there wasn’t a cow milked in 4/5 boroughs, but there were nine along with exactly two pigs on farms in Queens. The quick decline of urban agriculture hasn’t stopped it from remaining a powerful idea and, as these pictures show, the separation of cities from food production is relatively recent. The medieval city had its farming hinterland right outside the walls and pigs and chickens would walk the streets. Mexico City was surrounded by chinampas - some of the most productive urban farms in history. The terraced slopes that characterize pre-Columbian settlements in the Andes held crops. Urbanites would have access to markets but also supplement their diets with food cultivated literally in their backyards.

Spiritually, today’s urban farm has roots in the allotment gardens of Europe, which granted small plots of land in cities or metro areas for non-commercial farming. Germany took a particularly strong interest in the movement. The country rapidly urbanized through the 1800s as peasants moved into crowded cities and quickly faced food shortages and malnutrition. In 1864, Leipzig became the first German city to formally establish gardens to promote public health and nutrition, and the practice quickly spread to other cities. During the First and Second World Wars when food was diverted to the military or supply chains broke down the gardens became lifelines for residents. Today there are 833 allotment gardens in metropolitan Berlin alone and any train ride along the outskirts of a major German city usually cuts through a sea of little plots - although most of these are now used more as micro country homes than farms.

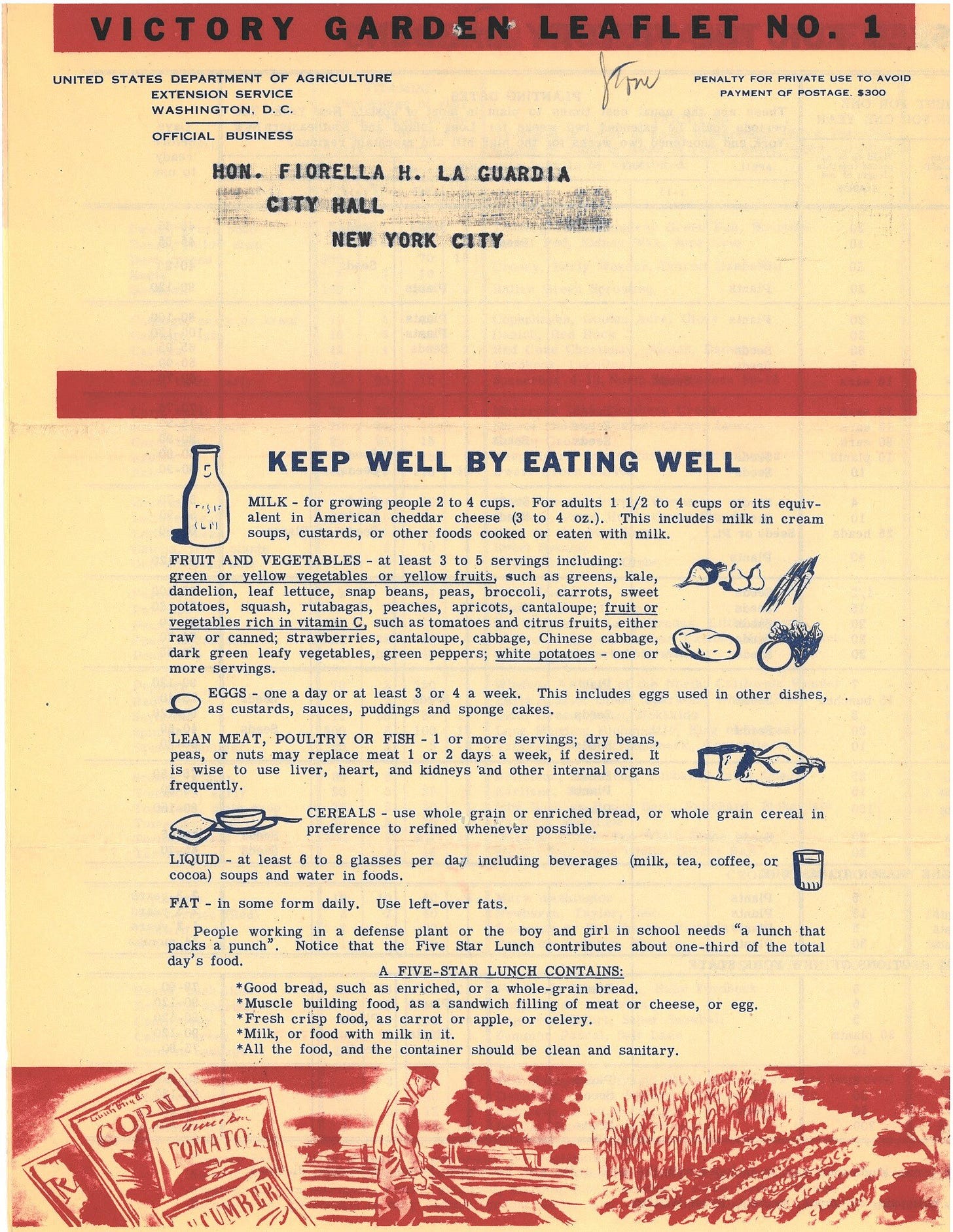

In the US, the “Victory Garden” movement inspired thousands of urban gardens to help with wartime food shortages in the 1940s. I’m partial to this, very dusty-looking one tiled by “The Boys of Ludlow Street.”

State agriculture departments and municipal governments issued pamphlets educating urbanites on seed stock, nutrition, and proper soil aeration. The New York Municipal Archives has a lovely digital feature on wartime farming in NYC. In 1944, one official wrote that “one would never suspect that the territory embraced by Manhattan, the Bronx, Kings, Queens, and Richmond Counties has very much suitable land for food production purposes, yet the people of these areas somehow contrived to find sufficient space for over 400,000 Victory Gardens in 1944.”

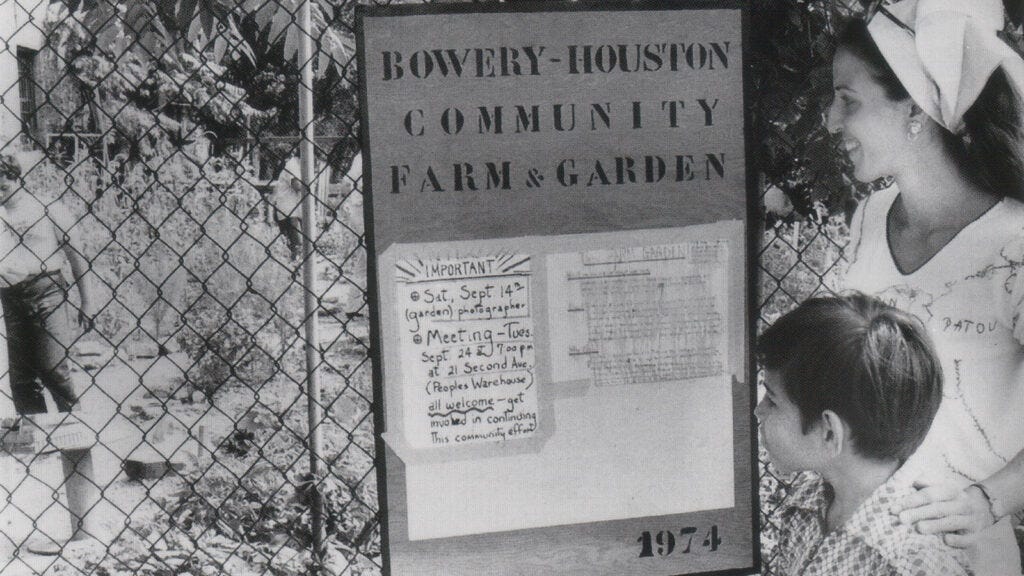

The urban farming craze ended when the war did as cheap industrial food and widespread refrigeration spread with the booming post-war economy. A little farm with a “patch of alfalfa for the rabbits” had the stench of the Depression and wartime rationing. The idea of urban farming would return, however, with the environmentalist movement of the 1970s.

The new crop of urban gardens springing up in New York and beyond were not primarily concerned with growing food out of necessity, but more as a way for the residents of hollowed-out cities to reconnect to nature and each other. Liz Christy, a pioneer of urban gardens who helped create the City’s official Green Thumb initiative said this to the Daily News 1973:

“The best thing about the garden has been the interest and involvement of families and especially children. So many children have been eager to take care of their own lots and besides keeping them out of trouble and teaching them something, it has also given them great pleasure to take home their crops.”

Christy’s quote brings out something important about why, in a modern society, we should think about urban food production. Detroit has an astounding number of urban farms, and in a city where 64% of residents report struggling to access basic food sources, there is a compelling argument that farms are both a good use of the city’s many vacant lots and fulfill an important gap in the food system. Across the world in Singapore, the tiny city-state is almost entirely dependent on outside imports to feed its residents. As a result the city has become a world leader in hydroponics and “vertical” farming to bring a modicum of food security to the island. What these two cities share is a set of unique conditions that make urban food production both viable and necessary. I don’t see a strong rational argument for urban farming in a place like New York City, which is reasonably well connected to food supply chains and where a lack of homes, schools, parks, and other things probably supersedes the use of precious urban land for farming. Christy’s quote highlights the other side of the coin - urban farming might no longer be totally necessary.. but it’s delicious, communal, and often mind-expanding. My friend Julia, the talented florist behind Outline Florals worked for years as a farmer in Oakland CA, and Brooklyn, including for a large rooftop farm in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. She had this to say:

Amazement is not a bad reason to do something, and if we shouldn't necessarily turn large swaths of urban land into farms out of necessity then perhaps it is better to think of these places as a form of placemaking and community building. I’ve been on the rooftop farm of Brooklyn Grange, there is a surreal beauty to seeing the Manhattan skyline with rows of crops in the foreground and the whooshing sound of the BQE behind you. It makes sense that a large amount of the farm’s profits come from hosting weddings.

Besides being useful, these places are fun to hang out in and educational to experience. Detroit is altering its 2013 urban farm ordinance to allow more types of public and community facilities to co-locate with farmland. As this suggests, our ability to enjoy urban food production is heavily influenced by the planning framework. The People’s Republic of Portland Oregon waived permit requirements in 2020 for beehives, chickens, and goats as long as owners could meet a set of noise and odor standards - and unsurprisingly these things flourished. The rules around food production are often strict, and maybe for good reason. Farm animals poop, crops require a lot of water, and all this has to happen with thousands of neighbors nearby.

Perhaps it is wrong to focus on farming when food production can take many forms. Growing up, a Ginkgo tree would deposit smelly fruit onto our sidewalk every October. Occasionally Chinese women would walk through our neighborhood with gloves and plastic bags collecting the pungent yellow berries to dig out the small nuts inside - which I’m told taste like chestnuts mixed with mushrooms and are prized in Chinese cooking. Recently I read about an urban planner (and fellow CUNY alum!) named Jordan Engel who, in an informal study, found 400 fig trees being grown in front yards throughout Astoria, Queens. One woman Engel spoke with was watering a fig tree that her father had planted with a cutting he’d carried as he immigrated to the city from Greece. Inspired by these stories Engel created the neighborhood’s first fruit tree exchange. A few months ago I was in an anonymous bowl restaurant when two, fully clad beekeepers walked in and ordered lunch on the restaurant’s iPads. Where the hell do you work? The Answer: Andrew’s Rooftop Honey, which apparently runs dozens of rooftop hives across the city.

These are forms of food production that don’t require big changes to the urban fabric. Currently, NYC only allows one edible fruit-bearing tree to be legally planted on New York streets, while in Warsaw, apparently, fruit trees are intentionally planted as a form of “free” food. A food-producing city doesn’t necessarily need to look like a row of tidy crops in a lot, but perhaps more like a street shaded by fruit trees, a park you can legally forage in, or chickens in the front yard. Chicken feet are not so surprising when you’ve seen them walking around.

I love reading your posts as I learn so much about the city I always wanted to call home but never did (now I just visit a lot). This reminds me of our community gardens program in Boston that my organization operates. They are such great examples of on-the-ground impact driven mostly by immigrant communities.

I learned so much from this post. As a historian, I thought of the now-classic work by environmental historian William Cronon, called *Nature's Metropolis,* about the interdependence of a city and its hinterlands in 19th-century Chicago--it's a big, doorstop of a book about the expansion of market relations and capitalism, about the city's place in nature and nature's place in the city... and lots more. Thanks for another great post.