Like half the world, I was caught up in eclipse mania last week. I didn’t make any special plans, but NYC was close to the path of totality so I figured I’d pop into the park to experience it. My local library was giving out viewing glasses for free but had run out by the time I got my act together, luckily a stranger was kind enough to lend me their viewing glasses to see the moon take a bite out of the sun’s orb, then I ran into an old friend who lent me her glasses once the eclipse reached it's NYC peak.

It’s a sublime coincidence that our moon happens to be both 400 times smaller and 400 times closer to Earth than the sun, thus producing a spectacular optical illusion. Although not in the path of totality, the eclipse was the feel-good event of the year in New York City. Freebies from local institutions, running into people you know, kindness from strangers, collective experience in large public spaces — not to exaggerate but these two hours were a nice display of why putting up with all the BS of city life can be worth it. A man next to me, mouth open, eclipse glasses on, said to no one in particular: “Woooow. The motherfuckin MOON is blocking out the motherfuckin SUN.” Kids were jumping up and down, and a smiling man in a wheelchair shared glasses with his health aide. It felt different than other large public gatherings. I had seen this same park descend into a debaucherous festival atmosphere when Joe Biden was elected, a day my friends still call Bidenchella. I remember eons ago when the Giants beat the Patriots in the Superbowl and everyone poured out onto 5th Ave in Brooklyn to celebrate. The eclipse didn’t depend on your sporting or political allegiances. This felt much more tender, much more ephemeral. It was almost childlike.

How does a rare event stop a busy city in its tracks? My urban design professor at UCL, Matthew Carmona once lectured me on the temporal dimension of urban design. Put simply, the environment changes places over time, and the use of a place changes depending on what time it is. Some of these rhythms are daily or even hourly. A train platform will swell with people right before a train arrives and then empty out. A playground will fill up with children around lunchtime and after school. Other rhythms may be on a longer schedule. Billion-dollar American Football stadiums (and their parking lots) will sit empty except for nine days a year. These are examples of the temporal dimension being shaped by rhythms of human activity, but as the eclipse shows, nothing shapes space quite like nature. William H Whyte documented the seating positions of workers outside the Seagram building and found that in spring and fall, they tended to arrange themselves in the sunny parts of the plaza like cats, while in the winter they didn’t sit outside at all.

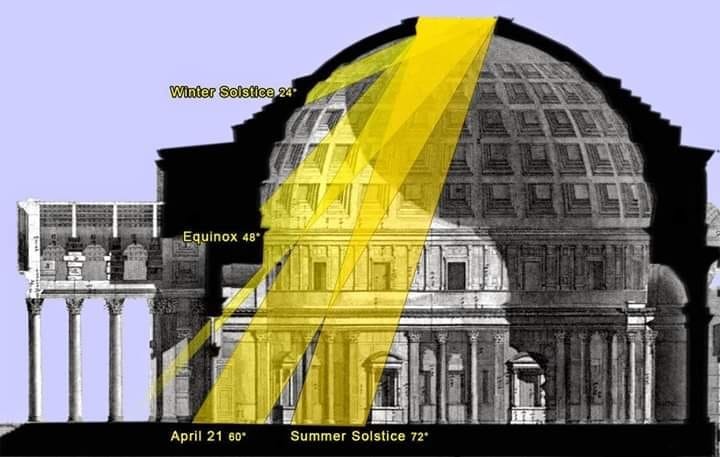

Harnessing this change can be spectacular. The hole in the dome of the Pantheon channels sunlight directly over the door every April 21st, the birthday of Rome.

Another favorite is “Manhattenhenge,” the twice-a-year period when the setting sun aligns perfectly with the street grid of Manhatten.

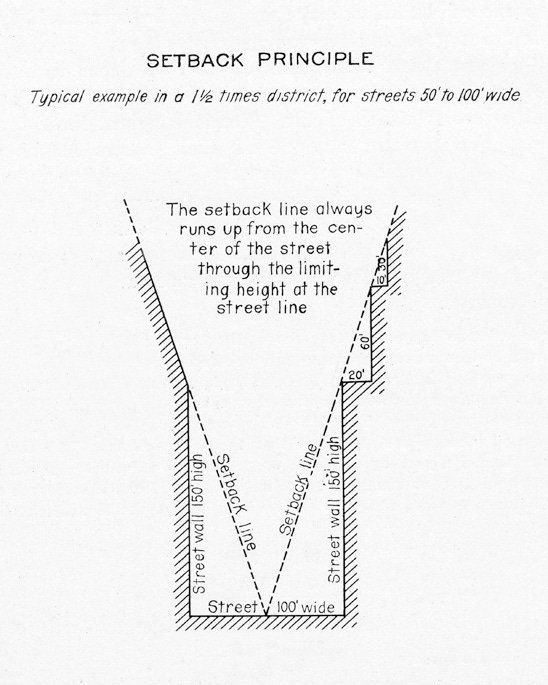

Besides looking dramatic, the sun is also (obviously) a source of warmth and light. The first NYC zoning regulation in 1916 was partially an effort to allow daylight into dark city streets. Regulators mandated that buildings of a certain height taper as they rose so the sun’s rays could diagonally penetrate the street.

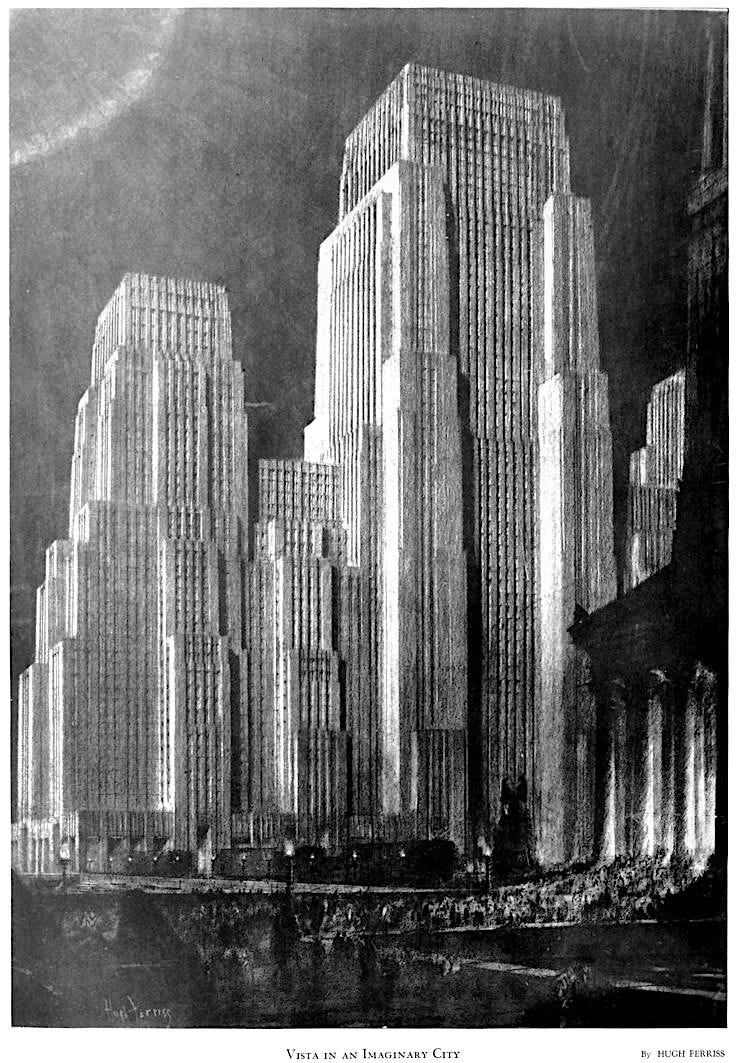

The architect and illustrator Hugh Ferriss was hired to draw imaginary buildings that conformed to the new law and essentially created the step-pyramid look of many Art Deco buildings from the era. It’s an amazing example of form following function. Pretty much every American city has at least one building that looks like this.

In some parts of the world, the light of day is something to be kept out. The incredibly narrow streets of many Arabic cities maximized shade in places that could reach 120 degrees. In parts of the Gulf states that haven’t become international shopping malls, you can still see this pattern. Below is Driyah in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Besides being essential for all life… the quality of the sun changes both daily and seasonally, making its impact on cities incredibly diverse. Some of these examples are functional, and some of them are spiritual and cultural. NYC wasn’t designed for an eclipse, but our streets, parks, and rooftops sprung into action as a container for people to literally be confronted with our place in the universe. No matter the intent, facilitating the use of space requires understanding the cycles of light and dark, cold and hot, busy and empty, that run through the year like a thousand clocks on different cycles.

I've read a lot commentary on the eclipse (I was on the roof of my Manhattan building, talking with neighbors I'd never met before), and this one is the best. Why? Because it goes beyond this-was-a-rare-moment-of-friendliness, to reflect on much bigger questions: urban design, buildings, and light. Nice!!