Welcome to the NYC Mayor Megapost.

The Democratic primary is on June 24th, and a way too long list of characters is hoping to be on your ballot (which, as a reminder, is ranked choice, meaning you get to vote for multiple candidates in your order of preference). To state the obvious, if you live somewhere other than NYC, by all means, save yourself and come back next week when we’re back to talking about nice parks and inane urban observations.

Rather than subject you to weeks of local politics, I made one giant newsletter. It’s lonnng, and written assuming zero knowledge, so skip around using the headings at your leisure. This is not about everything candidates are promising; It’s restricted to the built environment and planning issues, and for my own sanity, I’m ignoring the lowest polling candidates. But we start with how mayors actually do things, because when you understand how mayoral power works, it makes you a more critical voter.

How The Mayor Does Things

Development and Housing:

The mayor appoints the heads of pretty much every agency responsible for housing and development. Local governments in America rarely build things like housing directly (although maybe they should, and some candidates want to), but through planning, incentives, and regulation, the mayor has a lot of control over housing and development.

The mayor controls the departments of City Planning, Environmental Protection, and Buildings, and appoints members of the City Planning Commission. Collectively, these entities change the City’s zoning, regulate various building codes, and issue city-wide plans tackling specific areas of development, like waterfront planning or sustainability. Mayors use these agencies to decide what’s built across vast portions of the city. Walk along Kent Avenue in Brooklyn to see how transformative this power can be. Post 9/11, when there were fears that residents and businesses would desert the city, Michael Bloomberg pushed through developer-friendly rezonings of the Brooklyn waterfront, shifting it from a zoned industrial area to one zoned for high-density residential, and paving the way for today’s lines of shiny glass towers and luxury condos. Bill De Blasio launched Mandatory Affordable Housing so that a proportion of any new housing created as a result of a rezoning had to be affordable. These are just a couple of examples of the broad power mayors have to shape the development environment.

The next Mayor will inherit a city with an acute housing shortage, with vacancy at 1.7%, and a mind-boggling $3,800 per-month average rent. Creating new housing and a modicum of affordability through zoning, regulation, or otherwise will be a major part of the job. On affordability, the mayor also controls two entities that shape residents' affordable housing access.

The Rent Guidelines Board: Studies building operating costs and proposes rent increases for the tens of thousands of New Yorkers who live in rent-stabilized apartments. Under Eric Adams, the Board has passed rent increases every year; under Bill De Blasio, the Board froze rents twice. Already, several candidates are promising four-year rent freezes for rent-stabilized apartments.

The Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD): Provides public financing and planning for affordable housing projects across the city, and runs the majority of housing assistance programs and the affordable housing lottery.

Transportation:

Contrary to popular belief, the mayor does not control the subway. Subways and buses are operated by the MTA, a State agency controlled by the Governor. Through the bully pulpit and through the NYPD’s policing of the trains, the mayor does influence the subway, but they have more direct control over the fate of buses, which drive on streets owned by the NYC Department of Transportation. I’ve written about how the bus is the great, unloved hope of better public transportation. Subways are expensive to operate, maintain, and evolve. Properly built bus systems can rival light rail in speed and frequency, and many of the city’s poorest residents, who live far away from a subway station, the elderly, and the disabled, would benefit tremendously from a better bus network. A mayor committed to buses could have a relatively quick impact by directing DOT to create dedicated busways like the one installed on 14th Street, which banned cars during certain hours, speeding up bus travel times by 30%. Despite running as the “bus mayor,” Eric Adams has personally kneecapped bus lane projects throughout his tenure. Buses already feature as a huge part of candidate Zohran Mamdani’s campaign (more on this later), who has made the red-headed stepchild of transit a central part of his platform.

Finally, the Mayor has a lot of control over biking and plain old walking. DOT paints bike lanes, pedestrianizes streets, and installs street safety redesigns like road diets and daylighting. Under the current mayor, DOT has failed to meet legally mandated bike lane targets, often due to the personal meddling of Adams and aides. At the behest of powerful donors, often with car and truck-dependent businesses, bike lane and pedestrianization projects have stalled or been altered in Greenpoint, Fort Greene, Sunset Park, and Queens. But the mayor’s power can cut both ways. It’s unimaginable to think of NYC without Citi Bike, Times Square Plaza, or the Prospect Park West bike lane, but all these things were created by Janette Sadik-Khan, the visionary DOT commissioner under Michael Bloomberg. With congestion pricing already reducing the number of cars circulating the city, the next mayor will have an unprecedented opportunity to reallocate road space to walking and biking — and to our next topic: Public space.

Public Space:

Prepare to learn about the soup of city agencies responsible for public space. You may imagine a public space to be a park or plaza, but the largest public space in NYC is actually the street itself. Because DOT owns the sidewalk, it is, somewhat confusingly, a major shaper of public space. DOT runs the city’s COVID-era legacy programs: Open Streets & outdoor dining, as well as the longer-running Pedestrian Plazas program, which has been seeding public space in unloved intersections for the past decade. The Parks Department controls green spaces throughout the City, while a constellation of public agencies I won’t get into controls what you can actually do in public space—from concerts, to block parties, to playing tennis.

All of this is managed, and crucially funded, by the mayor. A big source of mayoral power is proposing the annual Executive Budget, which is then negotiated with the City Council to arrive at a final adopted budget. I’m bringing this up in the public space section because for much of our recent history, public space has been chronically underfunded. Despite the inordinate amount of enjoyment it brings, the NYC Parks department has never received 1% of the City’s total budget. The Department actually has fewer employees now than it did in the late 1970s. Eric Adams promised to put 1% of the city budget towards Parks, but has never done so. The COVID-era funding behind Open Streets has dried up. Many of the public spaces, from plazas to parks to open streets, rely on unsustainable volunteer labor and charity. The next mayor will inherit a city that is starved for public space and has less money to create it. The continued viability of Open Streets and, to a lesser extent, outdoor dining (which has already been established as a permanent, if flawed program) is very much in the balance.

The Candidates

Zohran Mamdani

We were always going to start with the State Assemblyman from Queens. Mamdani's charisma and laser focus on affordability have bumped him to a credible second place in the polls behind Andrew Cuomo. He’s done so despite (or maybe because of) being a self-described socialist Muslim with a funny name. What I admire about Mamdani is his jargon-free campaign, and there is no question he is the most talented communicator of the bunch. While his opponent, Brad Lander, emails me about “solidarity dividends,” and Andrew Cuomo says basically nothing, Mamdani has centered his message on a handful of easy-to-understand initiatives with obvious benefits for everyday New Yorkers: Free and fast buses, a 4-year rent freeze for rent-stabilized tenants, and free childcare. Since his campaign launch, a housing plan to create 200,000 new homes over 10 years has also been added. While the benefits of these programs are obvious, how they’d work or be paid for is not.

TLDR: Mamdani’s ideas are more feasible than opponents give him credit for, but getting even 1.5 of the things he’s promising done in a single 4-year term is a tall order. A vote for Mamdani is probably more a vote for a general direction than any specific policy proposal, which is something you can say for almost every politician and which isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

Free Buses

As a State Assemblyman representing an outer Borough, Mamdani has made buses a central part of his work. In 2023, Mamdani and State Senator Michael Gianaris funded a free bus fare pilot on 5 lines. Ridership grew 30%, with many new riders making $28,000 a year or less. The ridership growth on these routes, which in many cases were crosstown or did not compete directly with a subway line, would suggest that many new riders were people who would have otherwise walked or not made the trip at all. The economic impact of not having to walk hours to run an errand or go to work can’t be understated, nor can $34.50 a week in savings for someone making less than 30k a year. Expanding this out to a system-wide free bus program would be incredibly consequential to some of NYC’s poorest residents. Buses would speed up considerably since collecting fares adds time at each stop. One study suggested that eliminating fare collection would speed up buses by an average of 12%, without having to paint a single new bus lane.

Mamdani says that buses could be free for $800 million a year, or as he likes to phrase it, “just $50 million more than we spent on the new Buffalo Bills stadium.” That quip is revealing, the Buffalo Bills stadium is the pet project of Governor Kathy Hochul, who would likely need to pony up State funding to make buses free. A popular mayor Mamdani, might find the Governor, who is up for re-election, willing to throw NYC a bone. But even if Hochul was down, the money has to come from somewhere — a new gas tax, a tax on heavy SUVs, revenue from casino licensing, are just some of the proposed ideas. Mamdani’s campaign wants to aggressively go after outstanding fines owed by landlords to help fund free buses, but once those fees were collected, the well would run dry. Any of these would be politically bruising to implement. Asking people to pay for something they don’t use, no matter how good it is for the collective, is very difficult in our deeply individualistic city (see congestion pricing). SUV owners, landlords, and Casino magnates are not going to roll over as a small amount of their money is siphoned off towards some of the city’s poorest residents.

There is a greater philosophical question here as well. If we could find $800 million for transit, are free fares the best use of that money? NYC buses are slow, unreliable, and infrequent. Studies show that when people choose transportation, these are the factors they consider, along with cost. $800 million could be used to improve the service into something people felt was worth $2.90. $800 million could purchase 558 electric buses that are faster and more reliable than diesel, 8 elevators at subway stations, or fund significant chunks of any of the MTA’s various projects, like the 2nd Ave Subway or the future IBX. Free buses would be an immediate boon to some of the city’s poorest residents and cause a near-instant increase in bus speeds. But the fight to fund the program would be bruising, and the benefits would be limited without a corresponding improvement in service.

200,000 City-built affordable homes.

Mamdani’s pledge to have the city directly build 200,000 homes for residents in lower-income brackets would cost 100 billion dollars, about the entirety of the City’s annual budget, funded by municipal bonds that would require raising the City’s debt limit, which only the State legislature can authorize and likely wouldn’t. In campaign-promise form, 200,000 union-built, publicly funded homes may not be feasible, but if you aim for the stars and only reach the moon, then you’ve still gotten somewhere.

Even 10,000 city-built affordable homes would be a massive shift for a city that hasn’t built new public housing in decades. You don’t need to be a socialist to conclude that the free market alone is not adequately providing for housing. The great leaps in the city’s housing supply, the Mitchell-Lama program in the 1960s and NYCHA (the city’s public housing authority) in the 1930s, were all public-sector programs. Many candidates are calling for government intervention to unstick the housing supply, but Mamdani is going the farthest. It’s unsurprising that many of his most vocal critics are real estate developers. If you believe housing is a right, that its value is primarily in its role as a home and not in future resale value, and that creating it should not be strictly a for-profit enterprise, then Mamdani might be the candidate who aligns with your vision the closest.

On the less grandiose points of his platform, there is a lot to like on housing, public space, and beyond. Mamdani wants a four-year rent freeze from the Rent Guidelines Board. He is in favor of eliminating parking mandates - requirements that housing of a certain size build parking facilities regardless of whether they’re near transit or not - to increase the amount of space per lot that’s devoted to actual housing. He has pledged to have DOT capitalize on the reduction of cars in lower Manhattan post-congestion pricing to aggressively pedestrianize Midtown and Downtown. He wants a big funding boost for Open Streets, and he wants to give permanent design makeovers to the more successful ones so they’re not so dependent on volunteers to control traffic and set up things like tables and chairs.

I have questions about some of his boldest ideas, but everything in that last paragraph is relatively feasible to pull off. I will be ranking Mamdani happily on my ballot, and I will do so fully expecting him to shoot for the stars but hoping he can at least land on the moon.

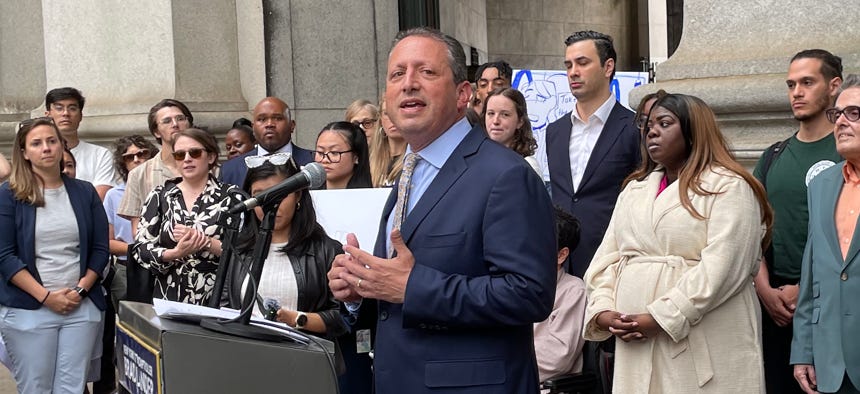

Brad Lander

Brad Lander is a nerd. Unlike, say, Andrew Yang, he has never leaned into his nerdiness and instead tries earnestly to dance at parades and hang out with the kids. To his critics, he is a technocrat with the annoying veneer of a Park Slope liberal dad. To me, he is one of the most potentially effective candidates in the race, someone who thinks deeply not just about what he wants to do but how to do it, and someone whose vision for the City is one I largely share, even if I disagree with some of his politics. I’m not alone, Lander is many planners’ choice to run the city (he would be the first mayor with an actual degree in urban planning). He began his career by leading the nonprofit Pratt Center for Community Development before becoming the City Councilman from Park Slope. Currently, he serves as the City’s Comptroller, sort of like the city’s chief financial officer, where he has been a persistent thorn in the side of Eric Adams. Lander’s campaign is impossible to condense into a single set of core proposals; his website lists 26 separate issues as a part of his platform. The policy brief he issued on housing, for example, is 36 pages long. A vote for Lander feels like a vote for a laundry list of progressive ideas from the last 30 years, but what sets it apart for me is a sharp focus on process, not just vision.

500,000 homes and a dramatic overhaul of the City’s housing system.

Lander wants to call a state of emergency, granting him powers to expedite the creation of 500,000 new homes over ten years. He wants a dramatic increase in the types of housing allowed (accessory dwelling units, basements, single-occupancy rooms, and more) through a relaxation of the zoning code, and to couple it with tenant protections like universal right to counsel, multilingual housing assistance services, strengthened good cause eviction, and a reformed Rent Guidelines Board.

As Comptroller, Lander is intimately acquainted with City-owned real estate, and a lot of his proposals are about using these assets to advance a pro-housing agenda, creating a rubric to assess the viability of the government’s land holdings — everything from hospitals, to golf courses, to garages and warehouses — to build housing. Lander wants prime parcels to be leased to affordable housing land trusts and non-profit developers. The advantages of using City-owned land are that it’s cheap(er), and the City can more easily set the rules - in this case, that whatever’s built on it is affordable. Lander’s call to build on some of the 12 city-owned golf courses has generated some attention, and his campaign estimates that taking four of these spaces for housing could generate space for 50,000 new homes.

Public land isn’t the only place he’s looking. Lander wants to implement the Faith-Based-Affordable Housing Act, a bill in the State Legislature that would allow churches, mosques, and synagogues to easily build housing on their land. NYU’s Furman Center calculated that religious organizations own about 84 million square feet of land in NYC, and 70 million square feet is unused! The land holdings of religious institutions reflect a capacity of worshippers that simply no longer exists. Over five million square feet of the land owned by religious institutes is parking lots. St Mary’s Church, down the street from me in Clinton Hill, has a landmarked church structure, a parking lot, and until recently, a substantial parish house and yard. Only the Church is in use. In 2020, the Church sold the parish house to a developer who built an apartment tower of affordable units. The developer also paid for the renovation of the churchyard for use by residents and parishioners. Lander wants to make transactions like this much easier. In the case of St Mary’s, the apartment tower was only possible because the area’s zoning permitted it, but 60% of the land owned by religious institutions falls outside of areas zoned for multi-family housing.

There is no signature theme to Lander’s housing plan (or any of his plans for that matter), but maybe that’s the theme in of itself — determined to wring housing from every nook and cranny in the city using whatever means necessary. During his time in the Council, Lander was a central figure in the rezoning of the Gowanus Canal, a rezoning which many would regard as a best-in-class example of housing creation under a flawed system. When the De Blasio administration announced its intent to rezone the industrial canal into a mixed-use residential zone, Lander, who was the City Councilman for the area at the time, became involved with a group of residents called the Gowanus Oversight Taskforce. The group produced a list of demands for the De Blasio administration to support the rezoning, including substantial affordability requirements, rehab of local public housing apartments, and the preservation or expansion of several beloved local non-profit community groups. Lander, who is often labeled as a technocrat, assumed the role of advocate and organizer. He is one of the few candidates in this race with an actual track record of helping to produce affordable housing, and he’s shown he’ll work any angle to get it done.

A new transit authority, Bus Rapid Transit, and expanded in-street public spaces.

I won’t break down Lander’s transit platform in detail, it is essentially a list of everything that bike and mass transit advocates have wanted for the past 25 years. He is firmly the choice of the cabal of evil transit advocates. Lander wants buses cruising down major streets in dedicated center-running lanes and bold street redesigns for expanded pedestrian and bike space. There is an elevated focus on safety, perhaps compared to some of his rivals, a crackdown on illegal e-bikes and mopeds, stricter enforcement for the city’s repeat speeders, and physically reshaping dangerous intersections.

Sitting above all this is a proposal to explore unified control over NYC transit. Right now, the State runs the subway, the City owns roads and streets, and private actors like Citi Bike and Lyft operate along the margins. Lander wants a single authority in charge of the entire thing, similar to Transport for London, which runs trains, buses, and everything in between. This would ostensibly give the City more power over its own transit without going to the State hat-in-hand. It could also eliminate the need for agencies to coordinate on bus and subway projects, since it would all be one big agency. From the everyday perspective, it could simplify the commuter experience— imagine Citi biking to a subway stop, taking that subway to Penn Station and grabbing LIRR to the beach on a single ticket. Still, who would fund this authority, and how exactly it would operate, are not details Lander is providing at this moment.

Taking my planner hat off for a second and putting my marketing hat back on (feels bad already), this is exactly the type of thing that I think is holding Lander back. Lander dubbed his desired authority “Big Apple Transit,” and his team made it the headline of his plan, complete with a spread in the Daily News. To make what is essentially a management scheme the marquee feature of your transit plan excites a handful of transit nerds and policy people and probably no one else. Lander may be great on transit, but he’s struggled to come up with a single thing as compelling and easy to understand as “Bus for free.” Hand-in-hand with all the bike lanes and pedestrianized streets is a lot more public space, year-round outdoor dining, a properly funded Parks Dept, and more open streets.

I’m not particularly optimistic about Lander’s prospects, but it’s difficult for me not to spend this much time with his platform and not come away impressed. I will certainly be ranking him, and I hope that if he loses, he will continue to work in City government, or at the very least, whoever wins will steal some of his ideas.

Adrienne Adams

I think Adrienne Adams, the current speaker of the City Council (no relation to Eric), would be a perfectly fine mayor, and I’ll probably rank her towards the end of my ballot. That said, there isn’t much for me to talk about here in the context of a built-environment-focused newsletter because she has put forward almost no concrete ideas. Her website doesn’t even have a section for her platform. Adams has spent a lot of her short campaign speaking about public safety, education, and her own integrity and management experience in a thinly veiled jab at Cuomo and Eric Adams. Again, this isn’t a criticism, these are essential things voters care about, they’re just not good for the purpose of writing this post. Adams has only been in the race since March, so it’s very possible that she will release plans as the race nears its conclusion.

Even without a platform, Adams isn’t an unknown quantity, having led the City Council for the past 3 years. The chaos of the Eric Adams administration makes it difficult to see her tenure too clearly. Many transportation and public space advocates look at her skeptically as someone who stacked the Council’s Transportation Committee with politicians from car-dependent parts of the City. Adams opposed outdoor dining and was instrumental in making the existing program seasonal rather than year-round, burdening restaurants with setup and storage fees. On housing, Adams marshalled the City of Yes package zoning reform through the Council, although with several last-minute concessions to more suburban parts of the city. Adams is competent, to the left of our current mayor but far from a barnstorming socialist like Mamdani or even a brainy progressive like Lander, and maybe it’s this middle-of-the-road identity that’s put her in a (distant) third in the polls.

Honorable Mention: Zellnor Myrie’s Housing Plan

Zellnor Myrie, a State Senator from Brooklyn, is polling in the low single digits but has easily the most ambitious housing plan in the race. Myrie’s plan pulls all the levers of Landers with a major focus on redeveloping NYCHA sites and what he’s calling a “Mega Midtown” — taking advantage of the depressed office market to reorient midtown from a largely professional neighborhood to a mixed-use one. Myrie also wants to summon entirely new neighborhoods from scratch on unbuilt sites like the Brooklyn Marine Terminal and Aqueduct Race Track. If you’re interested in any of this, I’d encourage you to skim the plan yourself or read Ryan Puzycki’s interview with Myrie over on

.Maybe it says something that a candidate with this type of vision has been largely a nonfactor in this race. In our given moment, it seems a decent amount of the electorate is voting based on personality, which brings us perfectly to the race’s frontrunner:

Andrew Cuomo

Cuomo has run a campaign completely on vibes. His campaign lacks any signature policy, and his housing platform was embarrassingly revealed to be cribbed from ChatGPT. He has not engaged in candidate forums or press interviews where positions on housing, transportation, or development have emerged. He is running a surprisingly shoddy, possibly unethical, campaign and is still the overwhelming favorite. A big part of his appeal is the perception that his demeanor will help the city stand up to the caprices of the second Trump administration. Whether or not that’s true is outside the scope of this, planning-focused primer, but more to the point, Cuomo’s hard-charging style has given him the air of a guy who gets stuff done. New Yorkers may remember him cutting ribbons at Moynihan Train Hall or the Second Avenue Subway and envision a builder-mayor capable of slicing through the city’s sludge of bureaucracy and corruption. Since we have little to look at in terms of his proposals for the future, it’s worth scrutinizing his record.

On housing and development, we can keep it relatively brief. During Cuomo’s time as governor, the average price of a house in NYC grew 77%, while the number of homes grew 3%. Cuomo engaged in some modest efforts to preserve or create affordable housing through the NY Home and Community Renewal, the state’s affordable housing agency, but his 11 years in charge went by without a signature effort to create more homes as the City and State became wildly unaffordable under his watch. His successor as governor, Kathy Hochul, proposed building 800,000 new homes in a doomed housing plan that would have eased zoning regulations to allow modest apartment buildings around transit stops and the legalization of accessory dwelling units. The program was defeated by a coalition of suburban politicians, but it’s scope shows how much more Cuomo could have been doing.

Cuomo famously declared a state of emergency to push the Second Avenue Subway — a 3-stop extension of the Q line that had been in the works for decades — over the finish line. Under his direction, the MTA pulled staff and money from across the system and poured it into the project, which a more recent assessment suggests deferred crucial maintenance on other parts of the subway. This aside, he got the MTA to do something on time, which is no small feat. When there was no ribbon to cut, however, Cuomo was all too happy to gut punch the MTA, the most galling example when he shifted millions of dollars from the MTA to bail out several upstate ski resorts. Cuomo also micromanaged and eventually drove off Andy Byford, the New York Transit Authority president widely credited for fixing the subway after the “summer of hell,” and known affectionately in the media as “Train Daddy.” Byford, one of the most respected transit officials ever, called working for Cuomo “intolerable.”

The other big transportation project delivered under Cuomo’s tenure was Moynihan Train Hall, a conversion of the Beaux-Arts Farley Post Office building into a new waiting area for Amtrak trains going into Penn Station. The project was essentially a facelift meant to ease passenger congestion in Penn’s underground dungeon. It did nothing to improve the actual frequency and reliability of trains. None of that is Cuomo’s fault. The various transit agencies involved had promised for years and failed to deliver. Cuomo took a personal interest in the project, setting an aggressive timeline of 3 years to complete and peppering the project with last-minute requests for aesthetic flourishes like a massive Art-Deco clock suspended from the ceiling. Michael Evans, the president of the Moynihan Station Development Corporation, who project managed the construction of the train hall, eventually took his own life from the stress. Notes about the clock and other material, and budget issues were found next to his body. Evan’s partner blamed Cuomo for his death in a since-deleted tweet. I don’t think New Yorkers particularly care about the former governor’s working style. If they did, then the suicide of one transit official would be just one of many concerns. But as someone who works in the public sector, and potentially one day indirectly for Andrew Cuomo…I do.

Many New Yorkers seem willing to put the city firmly in the hands of an egomaniacal man who follows no logic other than the accumulation of power precisely because he is an asshole and they feel our delicate moment calls for one. Looking at the type of person who has run our city for the past four years and who is running our country now, I can’t come to the same conclusion.

Well, I live in New York, but I also live in Pennsylvania, so I vote there, for swing-state reasons, but I still found this interesting to peruse, and I'm going to forward it to at least one friend who expressed confounded feelings about this election.

This was such a thorough and thoughtful breakdown of the candidates!