I spent a chunk of my work day last week trying to determine if a tree existed. A designer had been asked to revise a building project that threatened a street tree. Google Street View showed a spindly sweetgum tree planted at the site, but the owner insisted that there was no tree. The city maintains its own street survey tools (imagine Google Street View on steroids) which showed a tree at the location, but the last photos were taken in 2023. The NYC Parks Department undertakes a survey of all the trees in the city, sending hundreds of staff and volunteers to count, measure, and describe the city’s trees… but it only does so every 10 years, most recently in 2015. At the end of the day, don’t use technology to do what a human can do better. An IRL visit to the site of the tree revealed the below photo… No tree after all.

How do you lose track of something as solid and factual as a tree? Consider there are over 7 million of them in the five boroughs and each one is a living organism with its own agenda. This past July I attended the summer party of the Forest For All Coalition, a network of park advocates and public agencies devoted to increasing the amount of trees in NYC. Urban nature people are their own little subset of city professionals, and based on this one meeting a much happier and nicer one. At one point, a Coalition employee got up and tried to lead the room in a song about how great trees are - and people joined in, a level of earnest good spirit I couldn't imagine at a meeting of transit advocates. I sat at a table with the Chief Forester of Prospect Park, about as cool a title as you can get, and probably the only Chief Forester in America who takes a subway to work. I don’t even own a houseplant and was only at this event because my boss couldn’t go, but I got a crash course in the street tree, their positive (and mildly destructive) impacts on the city, and the particular challenge of caring for them.

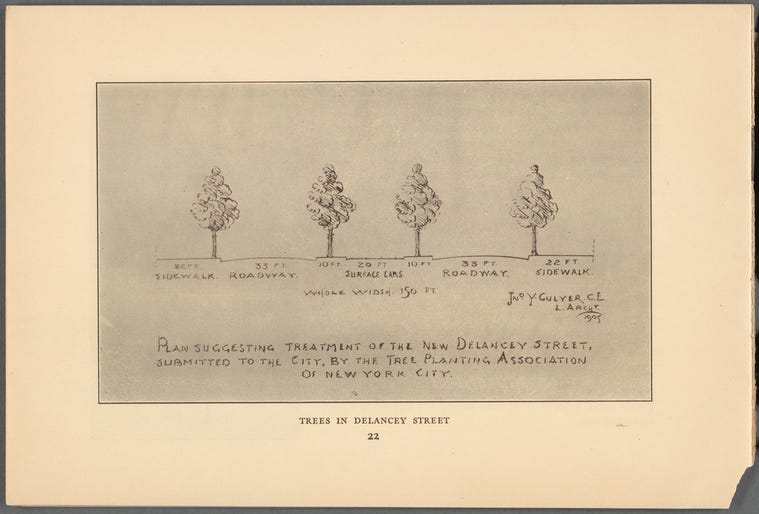

The systematic planting of street trees is fairly recent. In the mid to late nineteenth century, with the closing of the frontier, the emergence of romantic ideals of nature, and artistic landscape movements like the Hudson River School, it became fashionable for urbane East Coast men like Teddy Roosevelt to spend significant time in nature, developing manly tendencies, invigorating themselves, and communing with (and hunting) God’s creations. As president, Roosevelt appointed Gifford Pinchot as the first head of the US Forest Service. These men are best remembered for their roles in creating and running the US National Parks System, but, like many of the painters in the Hudson River School, these rugged nature boys actually lived in New York City. Pinchot, in particular, was a product of the progressive urban movements of the time, believing nature held a social utility as something that uplifted and dignified the urban resident, and that one shouldn’t have to go to Yosemite to experience it. The street tree, he wrote, was “the only form through which the residents of the city can come in daily contact with nature as we know it in the woods and fields.” Along with his wife, Pinochet became a patron of the Tree Planting Society of New York City, a group founded by a prominent New York City physician named Stephan Smith that undertook planting campaigns. Smith represents the other great driving force in the history of street trees, public health. Pinchot may have considered nature to be purifying in the spiritual and social sense, but more left-brained people like Smith were beginning to understand trees as literal purifiers. The science of photosynthesis was less than a hundred years old, but a consensus that trees were good for the environment was starting to emerge, and Smith was convinced that shade and fresh air were critical to fighting urban pandemics. The Tree Planting Society organized schoolchildren to plant trees around the city, organized tenement residents into tree-care societies, and advocated to city officials and architects to include trees in their plans. Tree-lined streets and boulevards had long been an architectural flourish but grassroots societies like these challenged the assumption that they were something reserved for grand avenues or the driveways of palaces.

Today tree-planting has emerged as a rare, uncontroversial streetscape improvement that ticks a lot of boxes for civic leaders, from heat mitigation to air quality and beautification. Forest For All calculates that NYC’s tree canopy absorbs 69 million cubic feet of stormwater, and 4.2 million tons of carbon dioxide every year. In 2007, inspired by a program in LA, Michael Bloomberg pledged to plant one million new trees in NYC by 2017 as part of his PlaNYC strategic vision. Unlike pretty much every goal ever set by a mayor, the City actually completed the program under the De Blasio administration… 2 years ahead of schedule.

This all sounds great until I take off my NYC supremacist glasses and look around. MIT’s Sensible City Lab calculates the canopy coverage of various cities. New York clocks in at 13% tree coverage (22% if you include parkland, which MIT does not), while a quarter of Vancouver is tree-covered. In Oslo and Singapore, trees cover 28 and 30 percent of the city respectively. As these calculations suggest, tree canopy is in vogue amongst urban data scientists and GIS analysts who have started to use AI and machine learning to interpret satellite imagery. Accurately showing tree coverage allows analysts to draw connections between coverage, urban heat, and a host of other environmental factors. The proliferation of data has let cities be more strategic about their urban forests. Boston Mayor Michelle Wu created the Urban Forestry Division in 2022 to implement the city's first Urban Forest Plan. The plan looks at every neighborhood in the city and triangulates everything from heat to road width to prioritize tree plantings.

Despite the increasing complexity of data and the popularity of top-down initiatives, tree planting remains driven by the grassroots. In 1966 Hattie Carthan formed a beautification committee for her street in her largely African-American Brooklyn neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant. Brooklyn street trees became her lifelong crusade, and Carthan formed a partnership with the underfunded Parks Department where the department would match trees with Carthan’s committee, providing 6 trees for every 4 the group bought and agreeing to share stewardship responsibilities. Similar arrangements have persisted ever since. Today you can request a free tree if you agree to maintain it. Over the life of the Million Trees project, the still underfunded NYC Parks dept enlisted schools, civic groups, and volunteers to complete the effort. 50,000 average New Yorkers worked for the program over its 8-year lifespan. Despite better-than-expected tax revenue, Mayor Eric Adams refused to restore the cuts he made to the NYC Parks Department despite the city’s first-ever major wildfire season burning swaths of trees in its marquee parks. Boston’s Urban Forestry Division has only 16 full-time employees to handle 40,000 street trees. The public picks up the slack, and often prods city governments into thinking bigger. Tree beds have become DIY gardening sites for thousands of everyday people - the flowers, “no pooping” signs, and even little picket fences are all small placemaking interventions on otherwise unremarkable blocks.

All this underlines a basic but important point about the urban tree: they’re high maintenance. They’re natural, but like farm animals, they need our care to thrive in an intensely human world so we expend considerable energy manipulating them. We cut away the concrete to give them little squares of soil to live in. Species like the London Plane are chosen for their hardiness over native species. For years, urban tree programs have propagated an unnatural amount of male trees, which tend not to produce messy fruit, seeds, and pods (male trees also spew pollen, which is why seasonal allergies in New York City hit so bad). Valencia, in a region of Spain famous for oranges, hasn’t banned orange trees from its streets, but it does deploy a fleet of automatic tree-shaking orange harvesters to try and minimize the impact of falling oranges on streets and cars.

But despite all our trimming and shaking, a tree isn’t really a domesticated animal, it can be guided but never tamed. Every day they slowly and steadily push against the boxes we put them in. The tree outside my apartment has been gradually pushing up the cobblestones around its tree bed for years. Its roots probably extend under the sidewalk around it, and once they’ve grown enough to displace enough soil they will probably crack the concrete slab — Trees have their own agendas which is part of why we love them. Each one is a defiant reminder that if you dig deep enough below all the apartments and We Works there is still dirt. The historian Phylis Anderson writes that the “tension between the rigidity of the grid and the looseness of the crowns of trees defines the classic New York City street.” One day maybe a squirrel will be able to run for blocks and blocks and never touch the ground.

Some random, urban tree stuff for your enjoyment

Urban Omnibus spoke to a photographer who has a weirdly compelling collection of tree-stump photos

Berlin was famous for its trees until most of them were destroyed in WW2

A very good blog of London’s trees. If I internalized any stereotypes of the English during my time there it’s their hobbit-like love of things that grow.

My favorite urban tree in the world is Rome’s Stone Pine, which is apparently in danger.

Gifford Pinchot*

I love this post as much as I love city trees. I also love that the small college town where I spend time (along with New York City) has had a Tree Committee since 1932, whose seven members “maintain and improve the canopy of shade trees,” which “contributes environmental and aesthetic benefits” to the town. City and country alike!