My grandfather died this past March at the ripe age of 98. Born in Manhattan, raised in Brooklyn, he traveled the world first as a pilot in WW2, then as a member of the occupying forces in Europe post-war, and finally as a dancer in the Martha Graham Dance Company (one of two Army pilots who somehow found their way from the war to Graham and the cutting edge of modern dance). But, after all this traveling, he lived out his life in New York and died a few miles as the pigeon flies from where he was raised.

“Roll me up and put me in the trash,” he used to say about what to do with his body. Of course, you can’t do this (legally anyway), and so last week I went with my mom and aunt to Greenwood Cemetery looking for a niche in which to put his ashes.

I’ve always been proud to have an unbroken familial line in this city going back nearly 150 years. It’s a blessing that makes me feel truly rooted to a place, and also a self-imposed curse because I feel some indescribable cosmic obligation to it. I walk the same streets and eat the same Katz’s sandwich as my grandfather and his parents, although I pay $15 more for it. Every city is full of ghosts but some of the ghosts here I know. The side of me that finds this lineage to be a blessing was thrilled that I would now have a relative at this premium address — a poor dancer amidst the mausoleums of the Pierreponts, Morgans, and Tiffanys… and Pop Smoke. I was also thrilled because, believe it or not, I come to the cemetery a lot.

This isn’t as weird as it sounds, Greenwood is one of the most beautiful places in the city. Established in 1838, it’s said that its 4,000 trees comprise the oldest landscape in New York. Its popularity as a picnic and recreation spot spurred the city to design both Prospect and Central Parks. People stroll it all the time, and the cemetery’s administration has done a nice job making it a place for respectful mourning but also art, nature, and social programming. I initially came to Greenwood because it was pretty, but I returned again and again because it was interesting.

What cities do with their dead has always been interesting to me. In the Western world, for as long as burial has been the Christian norm, people were generally buried on their properties or in their parish church. Dense cities have always challenged this approach since small church yards can only hold so many bodies, and by the 1800s cities like New York, London, and Paris were planning landscaped cemetery networks in their outer rings.

I try to go to the cemeteries of cities I visit because you learn a lot about a place very quickly by seeing who died there and how they mark it. Cemeteries are evidence of accumulated life. Also, as I’ve said before, many of them are simply beautiful. Below are photos I took in Highgate Cemetery in North London, which looks like the set of Dracula. The submerged street is known as “Egyptian Avenue,” a development of Egyptian Revival style crypts built on speculation and then sold to wealthy Londoners.

Here is Père Lachaise in Paris, which Highgate was inspired by. Balzac and Jim Morrison are buried here.

Below is Prazeres Cemetery in Lisbon, which has almost no in-ground burials, only mausoleums making it look like a literal city for the dead. The rooftops of its graves blend into the rooftops of Lisbon.

These places are rich with detail and story-telling.

The cemeteries I’ve mentioned served the relatively well-heeled and prominent. Outcast groups have had to rest elsewhere. Urban Jews had to take what space they could get in cities that were often hostile to their beliefs. Prague’s first Jewish cemetery was built over after residents complained to the King, so the Old Jewish Cemetery was established on a tiny spit of land and packed cheek-to-jowl for three centuries before it finally filled up. I’ve been to this cemetery and it’s actually difficult to move around.

Part of the appeal of places like Greenwood was that they were unconsecrated land, meaning any denomination or faith could technically be buried within as long as they could pay. Those who couldn’t pay still had to be disposed of. In 1869 New York City began using Hart Island in the middle of the East River as a cemetery for those who died indigent or whose remains were unclaimed. It’s filled with, among others, destitute Civil War veterans, tuberculous victims, AIDS victims, and stillborn children. It’s thought to be the largest public cemetery in the world with a million burials, roughly an eighth of the city’s current living population. It’s a catalog of the rejected and excluded, but also shows what makes cemeteries fascinating as places where cities clearly show their layers. Who was “out” in a given period of history is just as useful to know as who was “in.” A city’s social dynamics are snapshotted in its burial patterns.

Death is also a unique kind of planning problem. Where can we put people? How many can we hold? How do we make sure it’s sanitary? How do we ensure cultural beliefs around death can be acted out? These are issues that have inspired solutions like the Paris Catacombs and the mountain cemeteries of Hong Kong. I was amused to see on NYC’s zoning map a very thin ribbon of industrial land zoned adjacent to Greenwood, I’m assuming to allow for crematoriums and funeral homes to operate. Someone had to think about how this all works in the middle of a dense residential neighborhood.

Space is always a premium in cities. Hong Kong has recently unveiled the first “High Rise” cemetery in a tower that looks like the city’s countless other apartment blocks, ushering in a new potential era of high-density death. Of course, space is only an issue if you need a grave at all. Hindus prefer cremation, and maybe the most elaborate display of urban death is in India. Varanasi is an Indian city of 1 million where it’s estimated 20,000 people travel annually to die and be cremated on the banks of the Ganges River, one of the holiest places in Hinduism. There are hotels that cater to dying pilgrims, and the flower-draped crematoriums and temples on the river have become tourist destinations. The fumes they generate and remains placed in the river have also contributed to making it a tremendously polluted place. Sacred and profane concerns mingle. Funerary sites are places of spirituality and culture but also where we can undertake the unhygienic disposal of bodies away from homes and schools.

Enough time has elapsed from my grandfather’s death that I could view our trip to Greenwood with a certain analytical detachment. We don’t have crypt or tombstone money, so our options were the structures of densely packed niches the cemetery had set aside for storing ashes. The niches on the top and bottom rows cost the least. You pay more for eye level. If you want to be inside that also costs more, and if you want to be inside in an air-conditioned building that costs extra too. Do you want your niche to be glass-fronted or granite? Or maybe you want a little “memento shelf” installed.

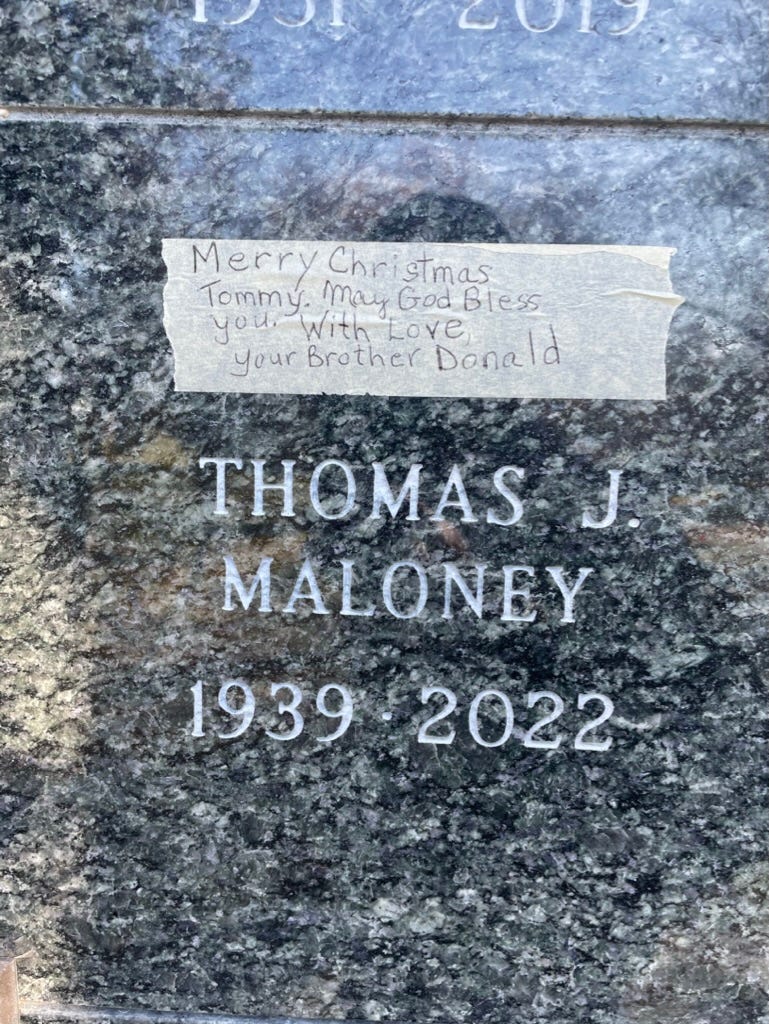

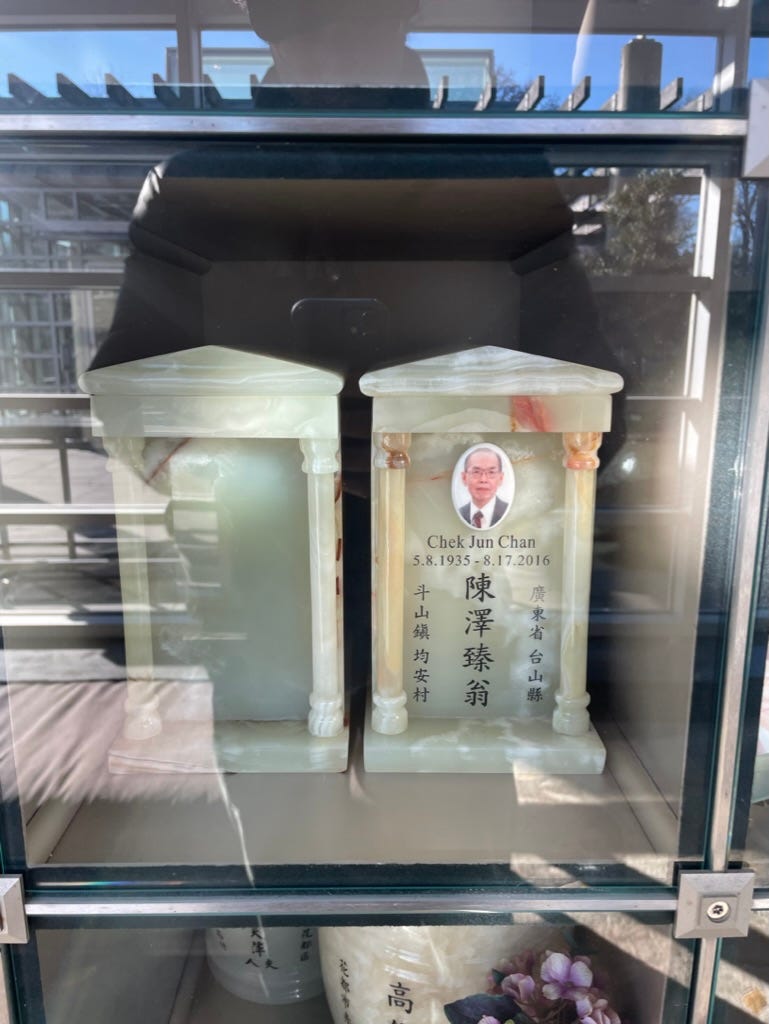

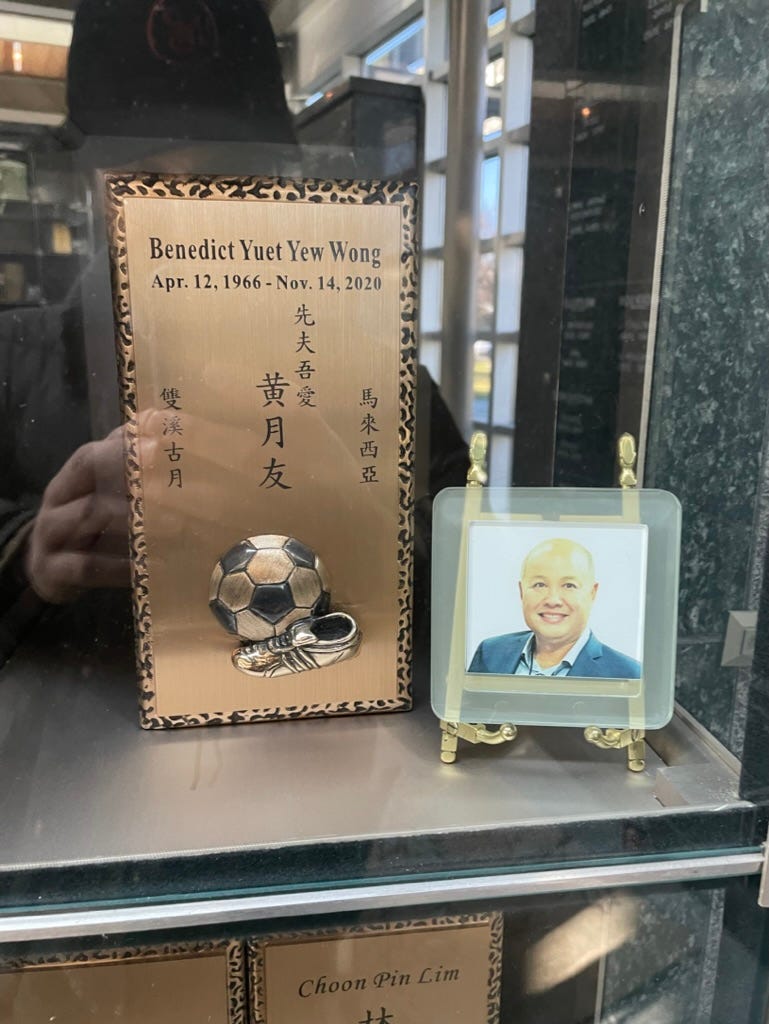

I was morbidly amused by all this. That’s New York baby! We haggle over real estate even when our souls have passed onto a higher plane. It makes sense, the cemetery has costs after all, and the Greenwood employee who guided us through it was patient and kind. I grew to view the cemetery as a little microcosm of the city itself, a piece of land that has to generate revenue for upkeep, manage space, grow its population, and somehow keep everyone happy. The ebbs and flows of the city’s population were so clearly written in the cemetery itself. The old Dutch names mix with the Anglo and Scotch, interspersed with a few Celtic crosses, Stars of David, and in the newer parts Virgin Marys and Spanish names. We settled on an outdoor niche shaded by wisteria that looked out past the southern wall of the cemetery into South Brooklyn, the general direction of his Sheepshead Bay childhood home. My grandfather’s neighborhood of niches carried the heavy influence of Brooklyn’s Chinese population (Greenwood is adjacent to Brooklyn Chinatown in Sunset Park). The glass-fronted niches seemed to be particularly popular with this community, and Greenwood has built incense holders, offering tables, and other bits of furniture meant to support Chinese funeral rites.

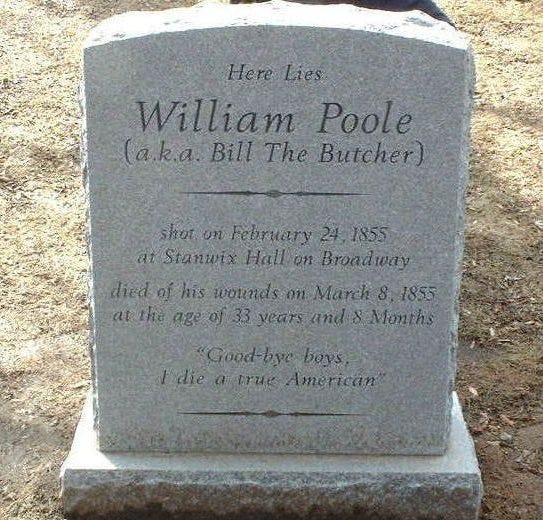

The sheer diversity of lives that have ended here is incredible. Ironically, Greenwood’s Chinese share it with the nativist gang leader, butcher, and firefighter William Poole, better known as Bill the Butcher and played by Daniel Day-Lewis in the film Gangs of New York. Poole’s gang violently terrorized immigrants across lower Manhattan in the mid 1800’s. His grave in Greenwood says “Good-bye boys. I die a true American.” Poole, in his violence, bigotry, and industriousness certainly was a true American. On the other hand, Greenwood’s Italians, Irish, Mexicans, Chinese, and Jews (my grandfather among them), in their own way, could call themselves the same thing.

Hey Matthew! Hovey has ancestors buried at Greenwood. Here's what I wrote after he and Lucy and I finally located the gravestones: "The Mitchells and Greens buried there in the 1860s, '70s and '80s include John Wroughton Mitchell (Hovey calls him Johnny Rotten) and his wife Caroline Green Mitchell, Gramma Brock's great-grandparents. A few years ago, I read that McSorley's in the East Village, the oldest bar in America, began when: 'In 1854, McSorley reportedly opened a tavern he called The Old House at Home on property purchased that year by real estate developer John Wroughton Mitchell.'"

The scissors! The dog! Beautiful photographs. This essay made me think about the history of potter's fields, the graves of paupers. Part of Washington Square Park used to be one, and the one on Hart Island in the Bronx has recently gotten attention--see the Radio Diaries podcast. Great reflections here!