The Tournament of Urban Animals will return next week.

In your mid 20’s, you hopefully have some money and taste. Everyone wants you at their bar, brands want you to buy their thing, musicians want you to listen to their song. People want you around, and if you have some sense, it’s easy to absorb what’s cool by osmosis. Now I’m old and culture is starting to pass me by. I don’t know what song is playing in the background of the bar, in fact I didn’t hear your question in the first place because it’s too loud in here. I don’t know the newest, cool place to go, and worse I feel like everywhere I did know has closed or sucks now (Fanellis). But maybe it’s not my fault. There are serious things like laws, economics, and politics standing between me, a beer under $9 and an accessible dance floor. Feeling rushed by your waiter? Consider that many restaurants in trendy cities needs to turn their table 3 times or more in a night to make rent. Wonder why the only place to dance is a club with long lines? Consider that dancing was technically illegal in most NYC bars until 2017. Urban planning and policy impacts your fun.

I’m temporarily living in the UK, and recently visited two venues that made me think about this. The first, SET in Peckham, is a social club that meanders over an old church complex. There’s a huge hall with pool tables and salvaged furniture, a kitchen, and a lounge bar with a dance floor. Outside is a large walled-in patio.

I went here twice in a day, first at noon for a free ceramics workshop in the yard. The age-range for this event went from 2 to probably 65. The crowd was diverse, and the vibe was wholesome. I came back at night when SET turned into more a typical bar. The crowd was younger with a strong art-school flavor and the feeling of a house party with room to dance, talk, or play pool depending on your mood. Between visits I killed time at Frank’s Cafe, also in Peckham, a bar set on the roof of a massive, converted parking structure.

The rest of the structure hosts artist studios, event spaces, and businesses in a complex called Peckham Levels.

Because I’m a nerd, all I could of was the permits! The licenses! The ZONING! I left determined to investigate how two buildings built to be something else ended up as bars/venues.

Specifically these spaces made me think about what planners and architects call adaptive reuse.

This is when a building made for one thing is converted into a building for something else. Soho lofts are examples of adaptive reuse (they were once factories), London’s converted railroad arches are adaptive reuse, LA’s masonic hall thats now a concert venue is adaptive reuse. You get the idea.

It can be incredibly difficult in the US to change a building from one thing to another because of zoning. Zoning is a regulatory tool that divides a place into zones with legally binding rules and regulations about what activities you can do and what you can build. Want to turn the ground floor of your house into a café? Better hope your neighborhood has a commercial zoning overlay. Want to divide your townhouse into a duplex? Better be zoned for multifamily not single-family residential. Even if a building is physically fine to use for something else, doing so can be tricky because an area’s land-use generally can’t change unless the zoning does. Every conversion of a warehouse into a loft, every bar in a church, every office into an apartment, usually has a lengthy and costly re-zoning process behind it.

All this makes cities slow to respond to change. In the WFH era, we have millions of square feet of unused office and commercial space that could be used for anything else. We continue to have abandoned plots spread through post-industrial cities that can only technically be used for industries which will never revive. There are many reasons these plots are empty (safety, cost…good article here on offices specifically) but zoning is one of them. Another downside is climate change. One study estimated that if the UK built all the homes it says it needs from scratch it would exceed its legally binding carbon emissions budget by 300%. The UN estimates that construction is responsible for a whooping 37% of all global carbon emissions. Recycling buildings, like recycling anything, reduces this impact.

But I’m not talking about serious things like climate change. I’m talking about having fun. When I was growing up people threw large, spontaneous parties on the soccer fields at Pier 40. The best modern art museum in London is in an old power station. Many people have been to a warehouse party. We go out to enjoy each other and activities, but also to enjoy great spaces. The effect of rigid zoning is we are sometimes denied the little thrill of having (legal) fun in a place that’s not a purpose-built bar, club, or venue.

Then there are building codes, permits, and local quirks like NYC’s prohibition era Cabaret Laws, which outlawed dancing and live music in bars that didn’t obtain a special license. Ignored at times, this was rigidly enforced by Rudy Giuliani in the late 90’s to close social clubs, venues, and DIY spaces that his administration viewed as a “nuisance.” And finally, there’s the market. It’s the economy stupid! Expensive real-estate means tenants are pressured to quickly extract value with low overhead. This incentivizes formula-following and discourages experimentation. That’s why you can get a seafood tower at any trendy restaurant in NYC– it’s a safe bet to sell and requires no cooking – just a shucker paid minimum wage. A social club for art student types doesn’t exactly scream profit.

So, there is a lot of heavy stuff shaping your night out.

Now, let’s take it back to London.

Starting with SET. SET is essentially an artsy pyramid scheme enabled by something called a guardianship. In the UK, owners rent vacant buildings they can’t immediately develop (because they lack the funds, the building is historic, etc) on a temporary basis at below market rates. In exchange for cheaper rent, the owner gets someone to pay utilities, keep the space in order, and give them a little money.

Charities can act as guardians, and SET is actually a charity with the mission of providing affordable artist studios. SET Peckham is one of several locations spread through London, and the only one not dedicated to artist studios. They are guardians to some crazy spaces, like an abandoned office tower in Woolwich with 250 studios and rents starting for 170 pounds a month. In addition to paying rent, members are required to contribute to the community. The clay workshop I attended was put on by artists who rent studios as part of this requirement, and workshops like this let tenants connect with each other and draw a crowd of non-creative Luddites like me to buy beers whose proceeds then go back into supporting studio spaces – again, an artsy pyramid scheme. The downside is obviously that once a owner decides they can develop a property the guardians must clear out, but it’s better than buildings sitting empty, and a way to insulate the artist from the rent pressures of London, even if just for a bit.

Guardianship explains SET’s relative affordability and quirky space, but what about the zoning? Well, there is no zoning in the UK, and its useful to bring in Peckham Levels here. I was surprised to learn that Levels is actually owned by the local borough government. The borough council leased the roof to Franks Café and the upper floors to an arts collective in 2007, with middle floors renovated into Peckham Levels in 2015. Ten percent of profits generated on site go into a community investment fund, and occupiers are required to teach or volunteer at a community resource center. This is possible because of how the UK does planning.

If you want to change the use of a building from one thing to another in the UK you just have to meet safety requirements and show the new use is in line with the goals of the local plan. Every local government in the UK has to produce a local plan, which details down to the sites within each borough the type of development and community needs in the area (Both Peckham Levels and SET were identified in previous planning documents as promising development areas). When someone applies for a use-change of a building, the local planners determine if the new use is in-line with the plan. If it is, they grant approval - no rezoning required.

As I pointed out in a past post, there is no legally binding “New York Plan,” and individual boroughs don’t have their own planning departments or make their own plans. Our zoning code is the closest thing we have to a plan for New York, and part of why it’s so detailed and restrictive is that it’s the only enforceable tool planners possess to influence the shape of the city. America is generally suspicious of plans made by governments (with some good historical reason) and so urban planners are relegated to tinkering around the edges – trying to reflect their goals and the public good through zoning maps and hoping that private developers fill it in.

So we have a couple of things coming together that makes London better at recycling buildings, for fun or otherwise.

A building environment that is generally friendlier to building reuse, through things like a lack of zoning and guardianships.

A system where local government grants approval to people changing a building from one thing to anther based on meeting goals rather than following rules. It’s not surprising that a goal of the Southwark Council (The council responsible for the Peckham area) to grant permission to development that “supports the delivery of public art, independent museums, theatres, and new arts and cultural venues.”

So a night out becomes a lesson in comparative planning. I want to be clear that I’ve simplified a lot here, and I’m by no means an expert in UK planning. I’m sure someone can point out all the flaws, but I’ll say that London has a real legacy of reinventing its spaces without tearing everything down. The Saxons dragged materials from the crumbling Roman buildings to make their homes. Bits of London’s medieval wall are incorperated into churches, halls, and homes. Hundreds of Victorian railway arches are today breweries, motorcycle dealerships, gyms, and florists.

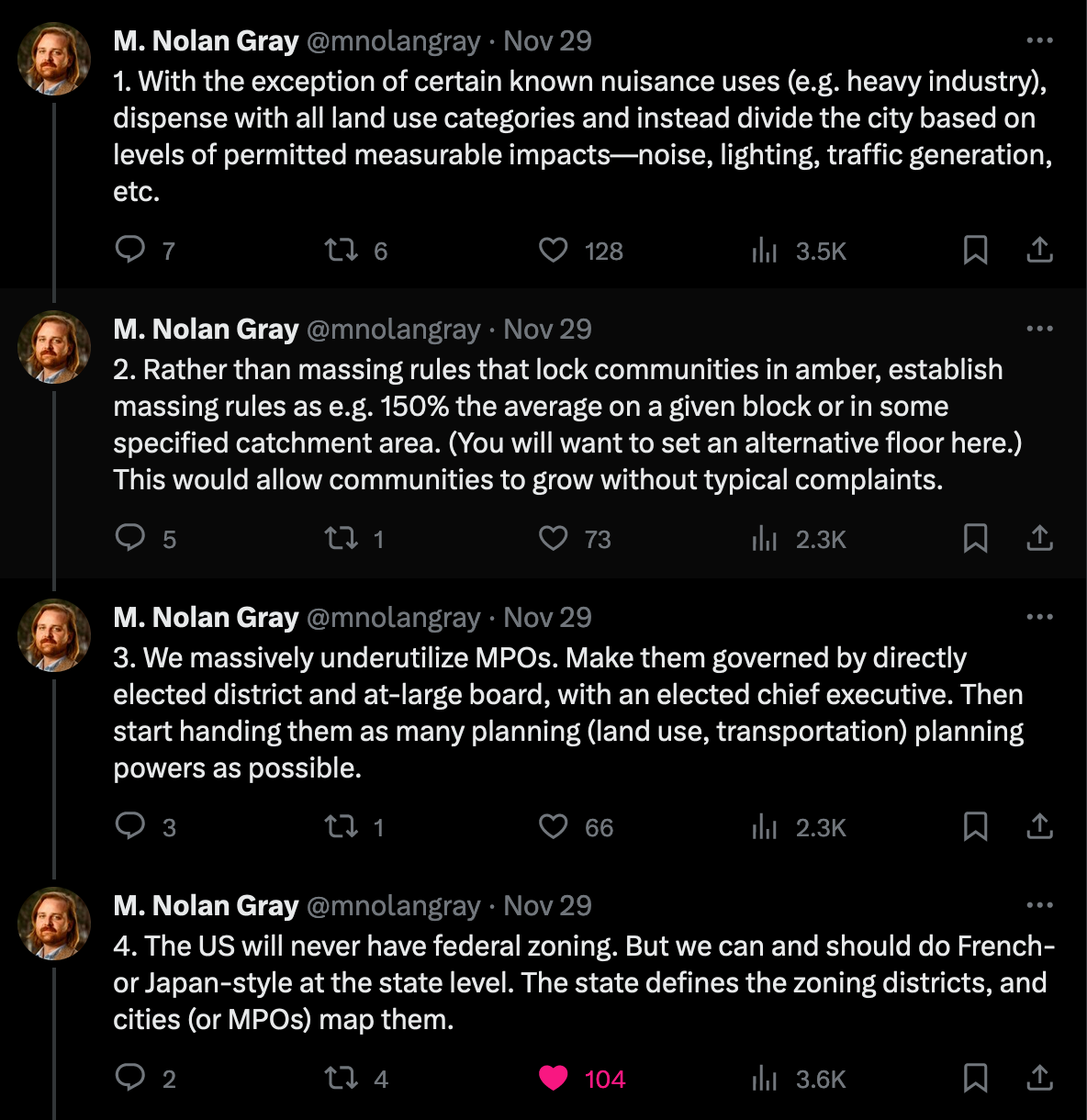

There have been calls to add to the zoning codes to make adaptive reuse easier in the US, but I think a better solution is to take a page from London and simplify (or eliminate) the zoning code and replace it partially or totally with robust local plans. I thought this guy made some good points:

Cities are often likened to organisms, with cells, inputs, outputs and metabolisms. Your body’s flexability is its greatest asset for responding to changing situations — our heartrate increases when we’re scared or thrilled, our pupils dialte to regulate the intake of light. When we put up barriers to changing buildings we inhibit our city’s metabolism and its ability to cope with change, and getting in the way of that is no fun.

Hey Matt - discovered your stack today. I’m a planner based in London, and a UCL alumni. Really enjoyed your article. I did some reverse research this year for a symposium at work, and didn’t know before that that the UK is pretty much the only nation with a planning system that doesn’t use zoning. I was fascinated to explore the differences and merits of the two systems. There are always rumbles by UK govt wishing to deregulate, about moving to more of a zoning approach. As it is, as you say, every proposal is considered on its merits. This involves time and resources, but means a broader range of favourable outcomes can be reached, and a townscape that ends up being less homogeneous, perhaps. I love the way you referred to policies as goals - in effect though some of those policies are pretty restrictive. If you want to change use from one thing to another it’s often prevented, with strict exception criteria, for example 12-24 months of marketing evidence that an office use is longer viable, before you might get a favourable change of use. But when the objectives line up, there is a fruitful and creative range of outcomes to shoot for. Hope you continue to enjoy exploring London!

Loved this one