This week I’m in Naples, the densest city in Italy. It’s not that Naples has a huge population or giant buildings, it’s just packed cheek to jowl. Kitchens and living rooms open right into the street, people hang their underwear up to dry on the sidewalk. Here’s some laundry I had to duck under in the Materdei neighborhood.

There isn’t much I can say about Naples that Caravaggio, Roberto Rossellini, or Elena Ferrante, haven’t described/depicted better than I ever could… but when has that ever stopped anyone with a blog? Like many cities I like, Naples has dramatic changes in elevation, and from the Certosa di San Martino— an old monastery on a hill in the city center— you can get a view in three directions that lets you take in the overall form of the city. A large amount of Naples is gridded on incredibly narrow streets. There is, I thought at least, a relative lack of large squares and piazzas. The waterfront hosted a steady stream of giant cruise ships the size of horizontal skyscrapers, and just beyond it a modern container port.

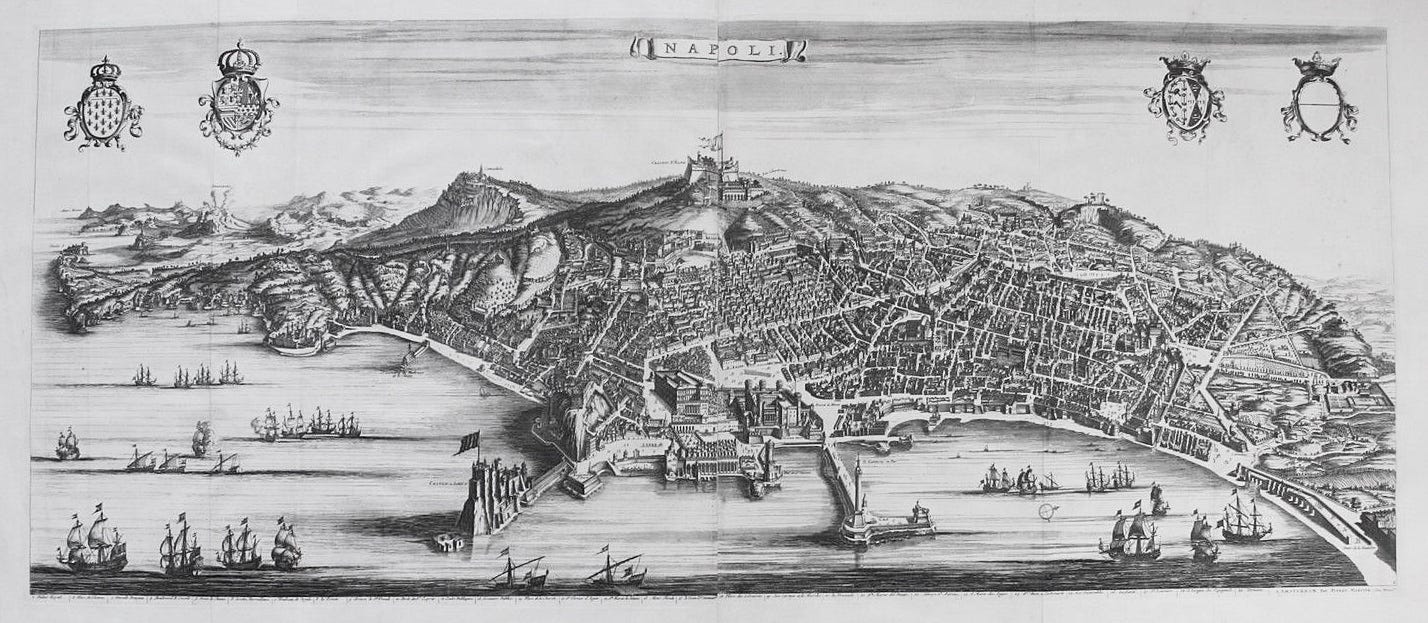

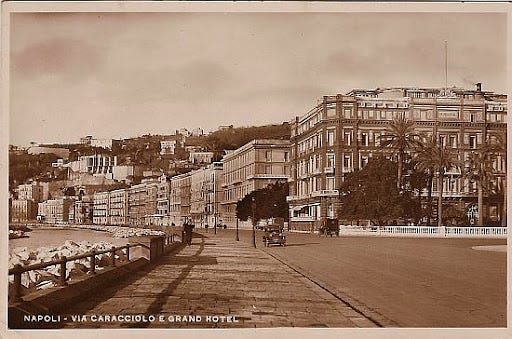

The fun thing about looking at the city from here is that the Certosa has a series of engravings that depict the city during past eras. Obviously, there were no cruise ships or container ports in the seventeenth century, but I was surprised at the relative lack of piers, warehouses, and docks. One engraving showed the waterfront as an elegant crescent of stately palazzos lining a beach of sand and rock, pictures from the 1930’s show many of these still intact. Naples wouldn’t be the first city to knock down something nice and replace it with something ugly, but did they really knock the historic waterfront down to build a cruise ship terminal and port?

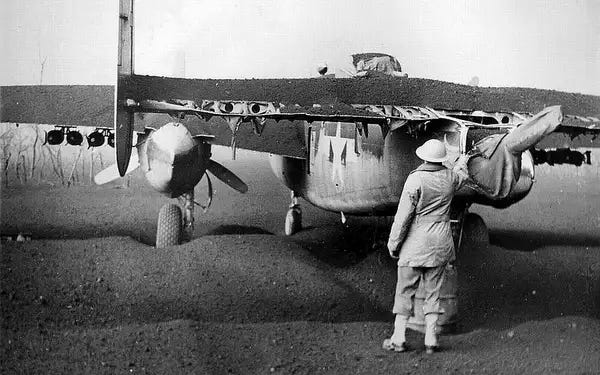

Yes and no. Mussolini wanted Naples to be a major stop for cruise liners, and the point of departure to the Italian Colonies. The cruise terminal he built is still part of the terminal used to this day. The Fascists also built the port of Naples into a naval facility. This made it a major target during World War 2, when Naples was extensively bombed by the Allies, and again by the Germans once American and British forces occupied it. The destruction wasn’t limited to the waterfront, and bombs inevitably ended up falling in residential areas, destroying major cultural sites and killing an estimated 20,000 people. After the war, the historic city had gaping holes it inevitably filled with more modern structures. I experienced a similar sense of whiplash living in London when I’d see a glass and steel building looming across from St. Paul’s Cathedral and wonder how a heritage-obsessed country with a planning system based on discretionary approvals could let something like this happen. When I looked into it, the answer was usually that whatever the new thing was built on was flattened by German bombs. The pattern of bombing in many European cities is still visible in urban form decades after the violence ends.

Can you tell I’m a fun person to be on vacation with? Am I the first person to enjoy a view of Naples in a clear sky and 70-degree October weather and be prompted into a long meditation on death and destruction? Probably not actually. The Monastery is full of memento mori— small sculptures, usually skulls, that act as reminders of the inevitability of death.

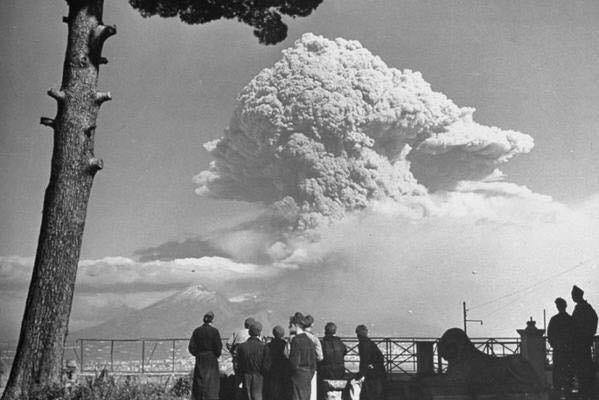

The region is also home to maybe the most famous scene of urban destruction, the burying of the Roman city of Pompeii in 79AD by the catastrophic volcanic eruption of Mt.Vesuvius. Depictions of the mountain, spewing lava, or smoking are probably the second most common image throughout the city after Diego Maradona, and the volcano itself is impossible to miss looming in the distance from most vantage points over the city.

Here is a much more benign version, rendered completely in pastry.

Vesuvius erupted periodically throughout the 20th century, killing 100 people in 1906 and again—dramatically— during World War 2 as bombs rained on the city. Three million people live in the volcano’s shadow today, and the Italian government has been encouraging people to move out of the “red zone” directly in the lava flow’s path. They maintain a plan to rapidly evacuate 600,000 people from the area’s “red zone” should seismic readers indicate a large eruption was imminent.

You can chart the history of planning partially by the term people use for “building over things.” “Slum clearance,” “urban renewal,” and more recently “regeneration” and “reuse.” Being here makes me consider a much simpler one, one that I’ve never had to use: rebuild. America hasn’t had to deal with the large-scale destruction of a city since the Civil War, and never in the era of aerial bombings or missiles. I’m reminded of our relative fortune every time I travel to Europe, and especially today as videos of Kyiv, Gaza, Beirut, and Kharkiv flood our screens. I don’t speak Italian, but in winks, nods, and gestures I’ve picked up that Neopolitains seem to have a great sense of humor. I have to imagine that between the bombs, skulls, and active volcanoes they know better than most that nothing is forever. Might as well cheat death on your scooter with a cigarette in your mouth and your baby riding on the handlebars.

"Can you tell I’m a fun person to be on vacation with?" Actually, yes! Great travelogue, history lesson, urban planning lore, and general enlightening yakking. Thanks for another great post.

Substack’s Finest and Bella Napoli…Stann’ cazz’ e cucchiar