Fresh Ground

Land reclamation in New York

Let’s pretend we have a machine that extracts a long vertical chunk of the ground — a core sampler like you’d see on a National Geographic special. If we aimed this device at the inland parts of Manhattan and pulled out a cross-section of earth, the topmost layer would be pavement, followed by dirt, coarse sand, and, deeper down, clay. At the very bottom would be bedrock, perhaps schist, but in some places, white Inwood Marble. Besides the pavement and whatever bits of pipe, wire, or buried trash we pick up, this would be a good cross-section of New York’s natural geology. The bedrock is, by and large, remarkably hard and sturdy, allowing huge building foundations to be reliably planted. If you’re willing to go into New York’s most depressing museum, the lobby of the 9/11 Memorial lets you see the destroyed building’s foundation works drilled into a wall of sheer rock.

Go towards the coastline, however, and the ground literally shifts. If we place our device around Bowling Green, we would pull up buried timbers from trees that once grew inland, dirt from street widening projects on the Bowery, and Oyster shells, revealing this was once part of the sea. “God made Earth, but the Dutch made the Netherlands,” the proverb goes. The Dutch knack for summoning firm ground out of their waterlogged homeland with earthworks and drainage projects was transplanted to New York, especially downtown around the original European settlement. The tradition continued under the English when the colonial administration sold “water lots” to local speculators. Some built piers, others simply filled in their patch of water with dirt, rubble, and tree trunks until they could pave over it and build.

For the past year, a pipe repair project has been underway outside my office on Water Street. As the name suggests, Water Street used to be on the water, but land reclamation means it is now three blocks inland. On the map below, you can see the parts of downtown created by land reclamation in pink.

One day, I watched a backhoe lift chunks of mud-caked trees out of a hole deep in the ground, which some enterprising colonial New Yorker had probably buried decades ago to stabilize the ground I was currently on. Billions of dollars of property and countless lives and livelihoods exist on this manmade rubble.

In 1980, the artist Eric Arctander traced the original shoreline onto the roads of the Financial District using a mechanical street marker.

Land reclamation would continue well past the colonial period. Ellis Island is partially constructed on rubble from the drilling of subway tunnels. Rikers Island was once 100 acres, but ballooned to four times this size with injections of construction rubble and coal ash. The last major land reclamation project in the city was Battery Park City, 92 acres of manmade land built over the west side piers, seeded with the construction rubble from the drilling of the Twin Towers foundations. Matter taken from one spot becomes the ground at another.

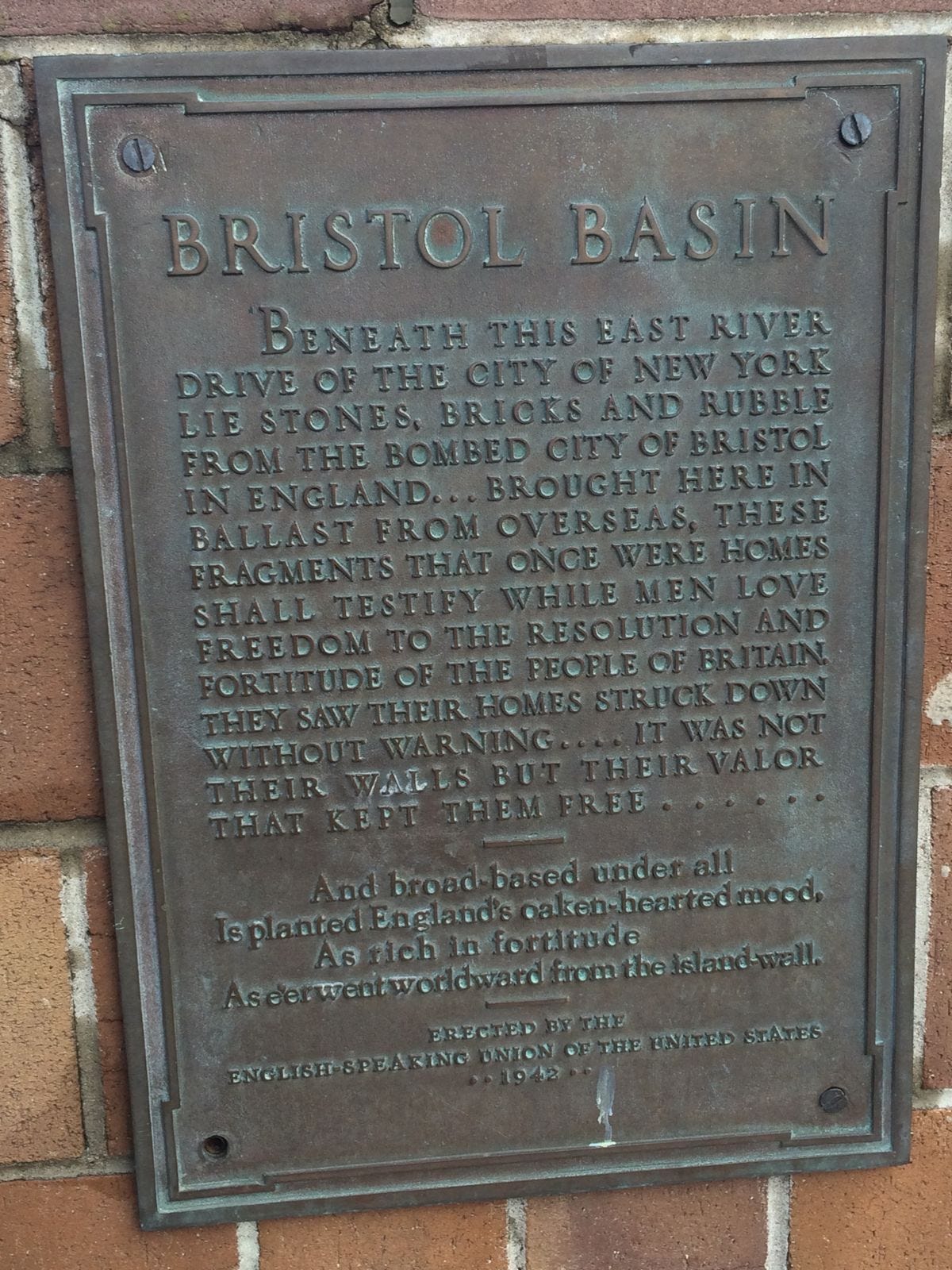

There is one part of New York where our core sampler would pull up building rubble from across the ocean, some of it older than the City itself. Waterside Plaza is a spur on the FDR Drive running along the East River. During WW2, ships would leave New York Harbor and deposit their cargo in Bristol, England. The emptied ships needed ballast for their return journey, and so they would load up with rubble from the city’s bombed-out buildings, stones from medieval churches, wood from timber-framed houses, and bricks from the Filton manufacturing area. The ships would return to New York and dump this detritus into the East River at Kips Bay, ironically close to where the British invaded Manhattan during the Revolution. The dumping was so regular that the area became known as Bristol Basin (which you can still punch into Google), and today, Waterside Plaza and a portion of the FDR run over landfill partially made up of the ruins of another city. A plaque commemorates the whole thing on the river’s promenade — a slice of the Blitz in NYC.

Despite the city’s endless thirst for buildable area, land reclamation has ceased to be a seriously considered planning tool. The era of cheap, readily available landfill has passed, and we are still reckoning with the environmental impacts of our Dutch, English, and more recent forebearers. Coastline extension largely destroyed the vast productive ecosystem that once ringed New York and left the land it created vulnerable to flooding. During Hurricane Sandy, the river flooded back to the lines drawn by Eric Arctander, reclaiming its ancestral coastline. On Maiden Lane, a supertall apartment tower has remained half built for years because its foundation is improperly drilled into the shifting artificial land along the river, causing a slight lean. Some headlines were made when the Rutgers professor Jason Barr penned an op-ed in 2022 calling for the extension of Manhattan by 1,700 acres to envelop Governors Island, but there hasn’t been a serious proposal to extend the city’s coast in decades.

The biggest earth-moving project in New York today isn’t being undertaken by developers, but by the Army Corps of Engineers, who since 2013 have been moving truckloads of sand and rock to stabilize the city’s southern waterfront. The Corps has moved 3.5 million cubic feet of sand in the Rockaways alone, 360,000 of them at Jacob Riis Beach. Riis was closed in 2022 for the first time due to erosion. The work there aims to replenish the sand levels and install stone jetties to soften the erosive impacts of waves. Victory over nature is usually temporary, but the speculative ideas of past New Yorkers gave us many gifts; maybe holding onto our beaches will be one of them. For now, if you want to see the future of land reclamation in New York, it's a backhoe pushing sand around on the beach.

I love this so much! Why have I always loved stories of the parts of New York built on filled-in land (or what you call, much more professionally, "land reclamation")? Something about it is utterly fascinating. And I'd never seen that cool Bristol Basin plaque even though I often walk along the East River promenade quite frequently. I will be looking for it next time.

You forgot about the rat layer, but otherwise this was a fantastic read!