I’ve been helping a resident group in Deptford, Southeast London, deal with a large luxury development going up next to their public housing complex on the banks of the Thames. The Thames isn’t like most urban rivers, it has two tides a day and the water level fluctuates wildly. At low tide, boats end up sitting on the riverbed and a huge swath of land is exposed called the ‘foreshore.’

During a site visit, the group’s leaders, Malcolm and Ken, took us down a set of ancient steps to the foreshore for a poke around. It’s not hard to find historical objects just sitting there in the riverbed. I found part of a clay pipe, probably from the 1700’s. These were sold pre-packed with tobacco and people just threw them into the river when they were done. I got a real nerdy kick out of finding this. The river is the city’s liquid storybook.

Picture a great city and I’ll bet you there’s a body of water somewhere in there — the ocean, a large lake, or river. While cities tended to treat their ocean and lake fronts as amenities, there are a lot of un-loved urban rivers. It’s fun to find a pipe in the river, but it’s also a reminder that cities as diverse as London, New York, Seoul, Cleveland, and Paris all struggle to some degree with a legacy of treating their river like a dump. Still, give me a good river over the sea or a lake any day.

Rivers move: The human eye is drawn to movement, and no matter how unloved the river is, the movement of water, wildlife, and boats will always be visually interesting. Even inspiring.

Rivers give definition: Rivers bisect cities. Your spatial understanding of them is delineated by rivers (Rive Gauche, the Southbank… Brooklyn).

Rivers are useful: Who doesn’t love a ferry. Cities developed on rivers because they were the highways of the past. Goods and people could be moved quickly and efficiently, and so many riverfronts were industrialized for this very reason.

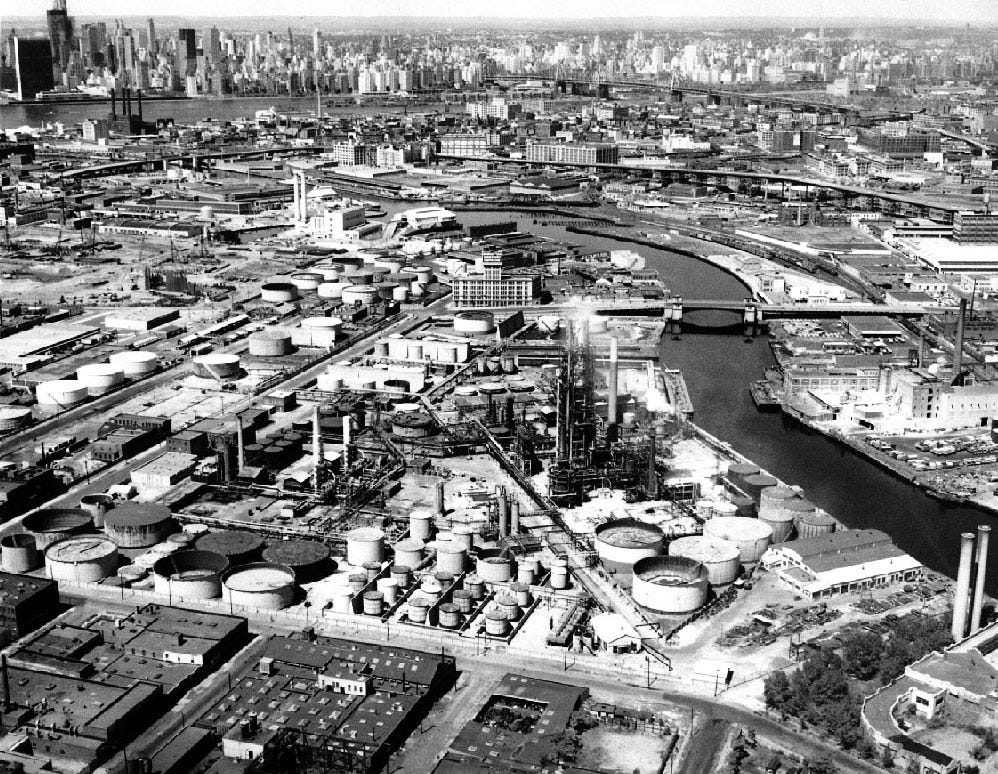

In my hometown, I think the transformation of New York’s rivers is the greatest planning achievement in the city’s 21st century history. In a city that seems increasingly unable to deal with its largest problems or transform itself at scale, it is worth thinking how amazing it is that people now want to spend time along the rivers. This was not always the case. I remember looking over the Brooklyn Heights Promenade as a kid at the abandoned warehouse piers which now host Brooklyn Bridge Park. The largest oil spill in US history actually happened in New York City on Newtown Creek between Greenpoint and Queens. It would take too long to describe just how industrial New York’s waterfront was so here are some pictures.

![Battleship USS South Carolina (BB-26) drydocked at the Brooklyn Navy yard, september 1912.[5570 × 4481] : r/WarshipPorn Battleship USS South Carolina (BB-26) drydocked at the Brooklyn Navy yard, september 1912.[5570 × 4481] : r/WarshipPorn](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff0427c4a-716a-4057-86b8-01f168b8f7ad_5570x4481.jpeg)

In the early 2000’s, I was walking my friend’s dog in Dumbo when it decided to jump into the East River. When we finally coaxed her out and bundled her into the car so we could go hose her off, the stink of the river filled up the entire vehicle. Her wagging tail sprayed droplets of East River water all over the windows (and me).

So, it’s not surprising that maybe the most important and obvious transformation is that the water is simply cleaner. No number of public parks or luxury condos will draw people to the water if it stinks. The federal Clean Water Act of 1972 curbed the ability of industries to dump waste in rivers (apparently, fisherman in New York bay used to be able to tell what color GM was painting its cars at its plant up the Hudson by looking at the color of their nets). The City then created its Department of Environmental Protection to protect its waters and enforce fines and worse on polluters. Enforcement slowly worked. If the gradual reduction in river-borne chemicals and smells has been pleasant for humans, it’s been a game-changer for wildlife. I once had to read a 200 page report by the Army Corp of Engineers on flood resiliency plans for New York Harbor, and the only thing I remember learning is that the Atlantic Sturgeon has returned to the Hudson River after decades of population depletion. They migrate up the East River and can be 15 feet long! There are about 250 fish species that troll the Hudson for one reason or another and many of them commute through New York City just like you. It’s possible to see dolphins play by the Statue of Liberty. We take for granted that we are the first New Yorkers for a hundred years to have water this clean and this teaming with life.

Here’s the part of the post where we talk about cold-hard planning =). The improvement of water quality has allowed us to re-imagine spaces that used to be for polluting industries as places for people. A lot of this has been achieved piecemeal by waterfront zoning. Zoning is a regulatory tool governments use to control land. It divides a place into zones with their own sets of legally binding rules and regulations about what activities you can do and what you can build. Zoning is how most American cities meet their planning goals. Since 1993, NYC has used a special zoning class for the waterfront to slowly wring improvements from anyone seeking to develop the waterfront. Developers building on the water must guarantee public access to the river, and the city incentivizes them to invest in waterfront parks and spaces by giving them density allowances for doing so (Domino Park in Williamsburg was paid for completely by a private developer in exchange for allowing them to build taller buildings than would normally be allowed). The result is that a public, landscaped riverfront has slowly taken shape paid for with private money.

The most dramatic changes to public space are not from the private sector but things created directly by the city. Here is Hunters Point Park in Queens.

The city restored the estuary-like conditions on the Queens coast that would have existed 300 years ago. This isn’t just nice for the species of birds and fish who make their homes in such places, but it’s nice to walk around, and evidence suggests that these types of wetland spaces actually absorb floodwaters and break up storm surges. It’s all part of a Parks Dept effort to gradually “soften” the edges of its riverside parks to harness natural flood protection (this strategy is sadly absent from the highly controversial East River Park).

Brooklyn Bridge Park is another triumph. The existing industrial piers were retained and reused as amenity spaces and parkland.

The coastline was softened and a big fuzzy green berm blocks storm surges and some of the noise from the Brooklyn Queens Expressway. I marvel every time I see kids on this little beach getting perilously close to (and even in) the river water. They would have called an ambulance immediately for you if you dipped your feet in here in my day.

The BBQ area in this park has the best view of any grilling spot in NYC, and it’s totally free. I throw a cookout here every year.

How come we can transform the waterfront, but we can’t open a subway station that’s not a billion dollars? Or upgrade our drains even though it floods all the time now? Partially it’s because once the city cleaned up the waterfront it became obviously valuable to developers (its the views), which let the city do some smart things to pay for upgrades. Developers make improvements to the waterfront at personal cost because they know it will enhance the value of their real estate. In Brooklyn Bridge Park, the city worked out a system where they sectioned off a small area for private development, which ended up being the hotel Dumbo House. Instead of paying property taxes, this hotel and the nearby condo building pay completely for the maintenance and operation of the park. It rubs me the wrong way that things the city used to just pay for now have to be coaxed from the private sector, but I think we can all agree that in the current neoliberal city this is better than nothing.

The second thing that enabled transformation is the City actually made a plan! NYC made its first waterfront comprehensive plan in the early 90’s, again in 2010, and most recently in 2020. While the plan isn’t legally binding, it lays out the vision and strategies for the entire waterfront, and many of the goals have been at least partially achieved. If this sounds incredibly obvious — make a plan, follow the plan — this is actually not how planning in NYC is done. There is no comprehensive plan for housing, or transportation, or anything really (London, where I am now, and many other major cities have a legally binding comprehensive plan). I’m not sure why the waterfront somehow gets a plan when other areas don’t, but I think the results show the value of laying out a vision in 10 year increments and giving everyone a strategy to follow.

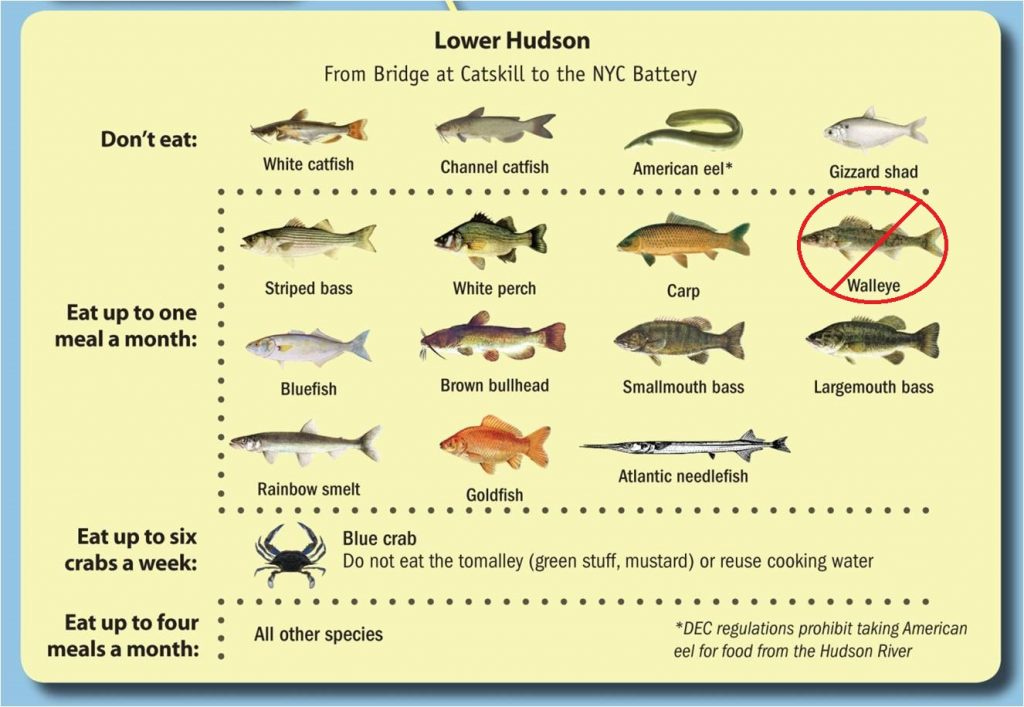

I don’t want to paint too nice a picture. The Bloomberg era-rezoning which allowed for dense residential development on the North Brooklyn waterfron had zero affordability requirements, and while it created one of the city’s most successful regeneration projects, it did so almost exclusively for the wealthy who could afford it. New York’s sewers overflow when it rains hard (which it is doing more now) and that overflow is still channeled directly into the rivers. You can not, by and large, eat more than one fish a month from NYC waters unless you want to poison yourself.

But I think its worth highlighting the successes and perhaps asking why this is something we seem to be able to do when we kick so many other problems down the road. I don’t have the answer but I think it’s a combination of the below:

The belief, over many years and mayoral administrations (Republican and Democrat), that the river can be an amenity, which allowed for long term planning.

An obvious, and relatively uncontroversial public benefit (turn abandoned space into parks and homes).

The alignment of private interest with the public good.

The tireless work of many small, but mighty, groups of people who lived by the rivers and advocated for them.

This last bullet point is worth ending on. The riverfront is a constellation of community groups like the Billion Oyster Project, or the Newtown Creek Alliance who push officials for improvements and propose ideas the City cannot or will not think of. A big part of why the City has been able to act with unusual vision on this one issue is because people, in many cases everyday people, saw the potential where others saw a big stink. I don’t know how to get these stars to align for the other issues of the day, but I’m thankful that in this one case they did. It is now my God-given right as a New Yorker to stand in Brooklyn Bridge Park and grill for free in full view of the skyline, and the only thing I smell is a hot dog cooking.

If you liked what you read, the most helpful thing you could do in the early days of this substack is click the share button and let others know!

"the city’s liquid storybook": beautiful! Another great example of a cleaned-up river, as I'm sure you know, is Boston and Cambridge's Charles River, beginning in the 1980s.