The distance between a cleanup and a crackdown can be thin. Two weeks ago, the Trump administration took direct control of Washington, D.C’s Union Station, part of a wider deployment of the National Guard and Federal law enforcement to fight crime. Never mind that crime in D.C. had been steadily declining. In an interview with Fox Business, Secretary of Transportation Sean Duffy said this.

“We’re going to take it back, and we’re going to drive out the homelessness, we’re going to drive out the crime. This plan is going to make Union Station represent the president’s vision of what America can and should look like.”

The telling part of the quote is the end, "a vision of what America can and should look like.” Trump is intensely focused on appearance. He cast his cabinet based on TV readiness and is determined to paint every blank surface of the White House gold. But the President is an extreme case of something fairly common in how politicians and people generally think about the condition of places. No matter how well a place works or how awful it might be under the surface, if it looks nice, it is nice.

A famous Italian once said, “Men judge generally more by the eye than by the hand, for everyone can see and few can feel.” Trump often draws on the language of cleanliness. Opponents are “disgusting,” and places he doesn’t like are “filthy.” At a press conference on August 11th, Trump explained his decision to deploy the Guard in these terms: “You shouldn’t have medians falling down in the roadway… I’ve never seen them look good. They’re always broken. We’re going to fix our roads a little bit. We’re going to fix our sidewalks. You have countries where every Saturday, people go out and wash their sidewalks…If our capital is dirty, our whole country is dirty.” As a reminder, this is his justification for a military deployment. Thinking things should be clean and shiny is one thing; using the threat of state violence to make it so is another.

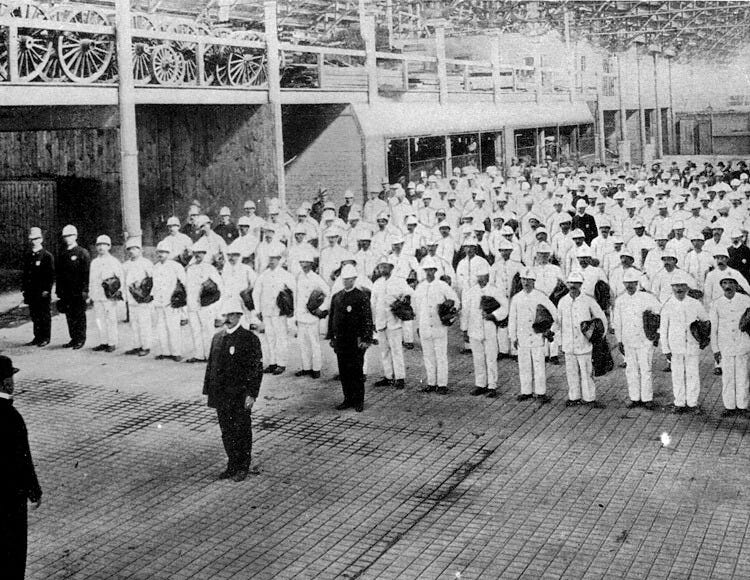

Maybe this leap isn’t so random. At the turn of the 20th century, an Army Colonel named George Waring was hired to create what would become NYC’s Department of Sanitation. Waring’s innovation was to structure the department into a quasi-military style agency where white-uniformed workers in pith helmets manually cleaned knee-deep horse manure off the cobbled streets. At the same time, a commissioner named Teddy Roosevelt was trying to reform the notoriously corrupt NYPD. He failed, but he did institute boot-camp style aptitude tests to appoint recruits, establish a system of medals, merits, and awards to reward good service, and give the department new uniforms and its own flag.

This military cosplay wasn’t unique to New York or even America. The National Parks’ workers dress a bit like Rough Riders; Tokyo Metro staff wear military style officers’ caps. The silly London policemen’s helmet was apparently inspired by the Prussian military’s Pickelhaube (before they wore helmets, policemen wore top hats). Municipal agencies love playing dress-up. Waring and Roosevelt wanted to inspire pride and discipline in their workers and engender the respect (and compliance) of the public. Aping military trappings was an easy way to do it. In a way, we have been walking down this path for some time, where the mess, chaos, and danger of cities feels like it calls for a uniformed force to sweep it all away.

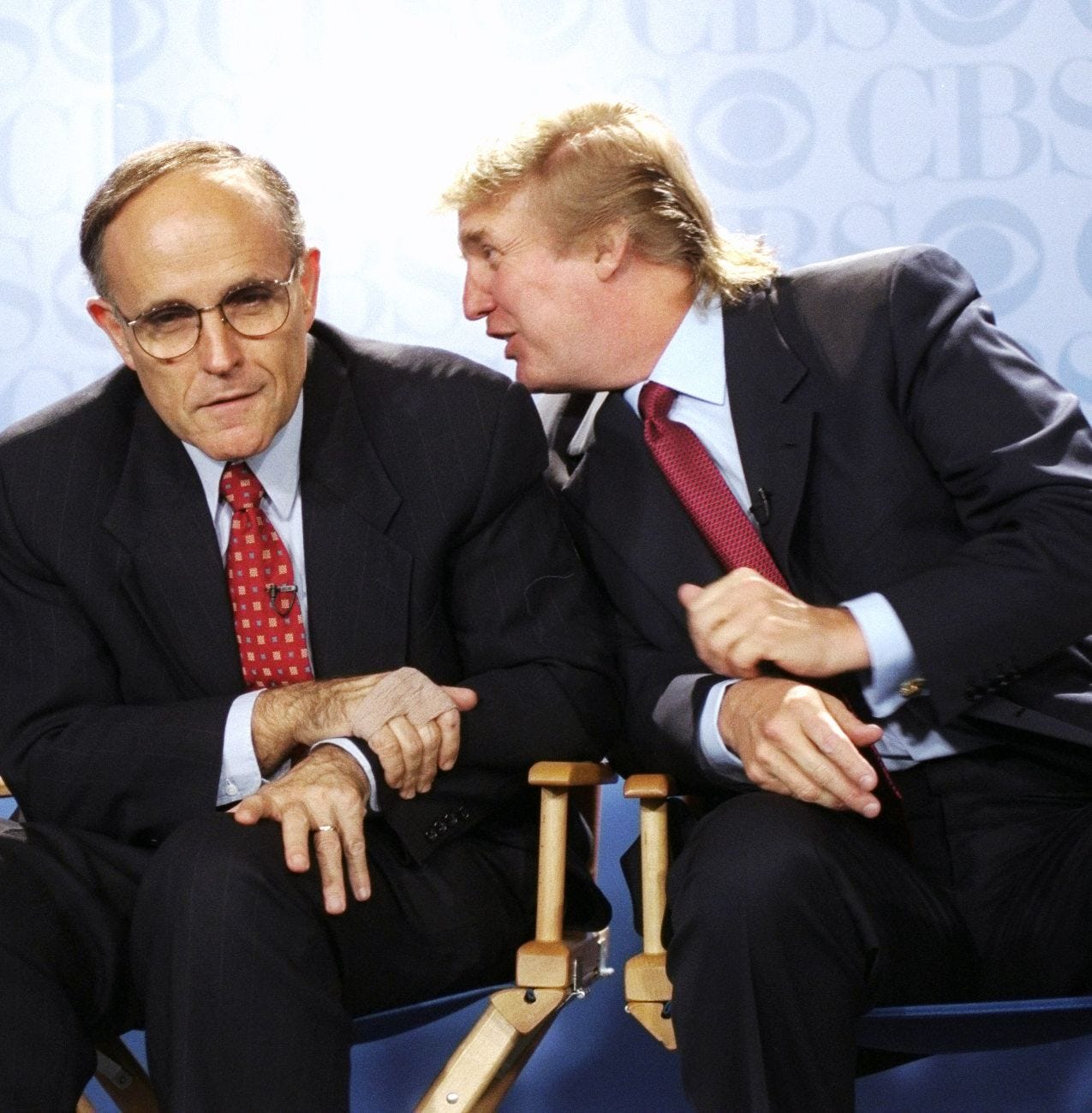

In the 70’s, it would have still seemed ludicrous to suggest that an armed police officer in a City dealing with thousands of murders and robberies should spend time chasing after a kid painting his name on a wall. We largely have two people to thank for applying police force to low-level, quality-of-life issues: Rudy Giuliani and William Bratton, the Mayor and Police Commissioner, respectively, of 90’s New York. Bratton and Giuliani were inspired by the “broken windows” theory of academics James Wilson and George Kelling, which drew a connection between the visual degradation of neighborhoods —burnt out cars, vacant lots, and broken windows— and later rates of criminality. Disorder should be nipped in the bud before it can turn into full-on crime by regularly cleaning streets, repairing windows, and removing graffiti.

The sociological underpinning of this article was, and is, questionable, but Giuliani, a former prosecutor, and Bratton, a longtime police chief, eagerly applied the idea to policing. It wasn’t enough to repair the window — you had to arrest the rock thrower. Today’s turnstile hopper is tomorrow’s murderer. Bratton and Giuliani authored Police Strategy Number 5 to outline their theory. It is one of the most important documents in modern American law enforcement, and is worth quoting at length. The paper’s first page states:

New Yorkers have for years felt that the quality of life in their city has been in decline, that their city is moving away from, rather than toward the reality of a decent society. The overall growth of violent crime during the past several decades has enlarged this perception. But so has an increase in the signs of disorder in the public spaces of the city. Public spaces are among New York City's greatest assets. The city's parks, playgrounds, streets, avenues, stoops, and plazas are the forums that make possible the sense of vitality, excitement, and community that are the pulse of urban life.

The year Police Strategy Number 5 was published, New York City experienced 175,000 violent crimes and over 2000 murders, and yet the paper starts with a discussion of public space. Defense of orderly public space is the justification for everything that comes next:

Over the years, enjoyment and use of these public spaces has been curtailed. Aggressive panhandling, squeegee cleaners, street prostitution, "boombox cars," public drunkenness, reckless bicyclists, and graffiti have added to the sense that the entire public environment is a threatening place. Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani has called these types of behavior "visible signs of a city out of control, a city that cannot protect its space or its children."

Here the culprits are named. It is not murderers or robbers or rapists; it’s loud, out-of-control people that are really the root of the city’s problems. As Giuliani’s first term as Mayor began, the police aggressively targeted low-level offenses with summonses for minor crimes ballooning from 175,000 to 500,000, and misdemeanor arrests more than doubling.

This era coincided with a precipitous drop in city-wide crime, and Giuliani’s mixing of quality of life and policing was, and in many corners still are, hailed as a success. But closer study reveals cracks in the logic. First, crime began to drop precipitously in 1991, two years before Giuliani took office. Second, the nose-dive of crime was a national trend, experienced by many cities, whether they changed their policing strategy and department sizes or not. This is to say nothing of the social cost of Giuliani’s programs, which put thousands of mostly Black New Yorkers into a highly carceral (and expensive to maintain) criminal justice system for low-level offenses, and often treated their communities like an occupying army. Researchers are still arguing about what caused the decline of crime nationwide, but various people cite the receding crack epidemic, bigger municipal and non-profit budgets, and an explosion in the number of prisoners as reasons beyond broken windows.

Had Giuliani read a different paper on the same topic (or more likely, had a different politician confronted the same issue), the results might have been different. A lot of researchers came to similar conclusions as Wilson and Kelling, but critically did not ascribe the role of improving neighborhood conditions to the police, or at least not to the degree they did. Later research would confirm what many anecdotally felt, that the definition of disorder was mediated by race and class. Is, as Police Strategy 5 says, a boombox really disorder? Or is playing music on the street actually one of the joys of city life? Finally, as a reformed proponent of broken windows points out in an article for Vital City, there is now an extensive body of research that questions the very premise that disordered neighborhoods will become high-crime ones.

Part of Giuliani’s legacy has been making disorder a right-coded issue. Commentators at places like the Manhattan Institute still write about it, although the breakdown of social norms during the pandemic got us to the point where even mainstream left commentators like Ezra Klein were starting to take an interest. It’s not surprising then that the President borrows so much from the language of broken windows, with immigrants standing in for the boogeymen of Giuliani’s era. It might be hard to imagine now, but before he was sweating hair dye and unzipping his pants for Borat, Giuliani was a hero to many New Yorkers, including Donald Trump, who has called him the greatest mayor of all time. Roy Cohen is often cited as Trump’s political mentor, but the staged perp walks, demonizing press conferences, and free-wheeling use of force that Giuliani popularized feel just as foundational. Trump’s innovation has been to simply replace the cop on the quality-of-life beat with a soldier.

Of course, all people suffer under dirty and disinvested environments. But like many topics, the left doesn’t really want to talk about the problem, and so they cede the proposing of solutions to the right. I know plenty of progressive urbanites who grumble privately that they hate how delivery drivers ride their e-bikes on the street, but then freak out when a City Council person from a red neighborhood proposes a ban or a crackdown. The left is bad at proactively offering solutions to disorder that don’t hinge on enforcement. Maybe the dark, but probably widely felt, belief that a place can become so out of control that only great force can purify it is simply too ingrained; you can see it everywhere from Batman’s vigilantism to Robocop to the story of Sodom and Gomorrah. Of course, the National Guard won’t fix the medians or clean up the sidewalks. But, like sanitation workers in white uniforms, it’ll be good theater, everyone will look like they’re really doing something, and certain types of crime probably will go down. But it will all be done at great cost for temporary gain, and as Abraham pointed out to God before he destroyed the supposedly irredeemable cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, a great deal of the righteous will be swept away with the wicked.

This should be a New York Times or Wall Street Journal guest opinion essay! Politicians and urban planners should be studying this essay for years to come.

Oh my god, don't get me started on the 90s - the reign of Giuliani-Bratton and their racist policies, devoid of any cultural, social, or economic context. Homeless families=criminals, boom-boxes-crimes. Wilson & Kelling were conservatives whose writing helped usher in the war on drugs and the mass incarceration of African Americans. As a social worker in NYC at that time, the impact I witnessed in poor communities with few services and resources, was devastating.