City-Shapes: Express Yourself

Grids, wiggles, God, money. Urban form is a language of expression.

My first year of grad school I started a note in my phone called “Urban Planning…WTF,” after realizing planning was way weirder and less rational than its nerdy reputation suggests. Some examples of things I saved:

This man, whose job is somehow to advise on the design of cities in video games.

This theoretical plan for a completely food self-sufficient NYC

And lots of pictures of Eric Adams looking at things and pointing at stuff like he’s a certain other world leader.

But the majority of the tidbits had to do with the origins of various urban forms — or the shapes of cities. By shape I mean the paths and nodes created by streets, buildings, and open spaces. Everyone is loosely aware that their city is a shape even if they’ve never thought about it deeply. Moving through New York is a series of right angle turns while Marrakesh is a meandering stroll. I’m fascinated by urban form, not just because it determines how we experience cities but also because a shape is an expression of a place’s history, and often of its values (or at least the values of the people who laid it out). This post is basically an excuse to write a little about the stranger shapes I’ve come across and maybe draw some connections between them.

Here’s a dramatic example. If you’ve ever flown over the American West and Midwest you may notice a lot of squares. Here’s Iowa.

Zoom in a bit and you can see each of these squares is bounded by roads, and each square is filled with little farms. The squares do not respect patches of trees or rivers, they just cut right through.

If we look somewhere more urban, like Cedar Rapids below, the squares get lost a little in the street network, but you can still make them out if you look hard enough.

The reason large swaths of America look like this is because Thomas Jefferson said so. In the 1780’s the government needed a way to categorize and sell its vast lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. Jefferson helped author ordinances that defined the west as a series of 1x1 mile squares. Administrative boundaries drawn by surveyors under this system became physical ones as roads, farms, and eventually towns took hold within them. The “shape” of the region was determined mainly by the government’s need to efficiently sell land and raise funds (being broke post-Revolution), but its not hard to see Jefferson’s values and beliefs expressed through the plan. Jefferson was skeptical of cities, he envisioned the country as an agrarian utopia sparsely populated by (slave-owning) gentleman farmers like himself, largely self-sufficient on their lands, exporting raw goods to the nasty cities and factories of Europe in exchange for nice porcelain, good wine, and the other outputs of an industrialized society.

One family per mile is not exactly the type of density that suggests an urban or industrial future, and the spread-out character and “square-ness” of parts of the west remains.

Jefferson was consciously planning at the national scale, but even in much older settlements that lack formal planning there is usually a logic hidden somewhere. In medieval England the lord would rent skinny rectangular plots out to freeman. These burgages (burgage is where we get the word borough) had a side facing a common road, a small house or workshops, and a decent amount of open space for grazing and agriculture.

Rectangles were easy to measure and easy to tax, and if you were willing to chop them up a bit or fudge the edges you could make them fit into pretty much any road network.

In the oldest parts of London it’s not hard to see traces of burgages. As agriculture moved out of the city, more and more of the burgage plots were taken up by buildings until you got the rough shape of places like Fleet Street today – a series of skinny rectangular buildings laid out cheek to jowl.

As Jefferson and English Lords show, property law is often at the root of a place’s shape, but religion and belief is another big one. New Haven was laid out painstakingly by Puritans to match the proportions of the biblical Temple of Solomon. The Chinese historically laid out cities by Feng Shui principles to maximize the harmony and flow of qi (life-force) throughout the space. The Forbidden City in Beijing is laid out north-south, with its number of gates, building sizes, and layers of walls all determined by Feng Shui principles and lunar cosmology.

Of course, this layout is also just a really good way to express the splendor of the Emperor, whose palace goes smack in the middle. When people in power consciously shape cities they tend to do so in ways that preserve their power. In the name of sanitation, Haussman flattened the cluttered medieval parts of Paris to make wide boulevards like Rue de Rivoli that let in light and air. These new avenues were also designed to be too wide for protestors to barricade, as they had done during the French Revolution.

Preventing protest, emulating God, making money, respecting the Emperor…what you’ll notice about the examples so far is they’re not exactly rooted in the public’s quality of life. Weirdly, one of the older examples of a more quality-of-life focused settlement approach comes from the Law of the Indes, a colonial how-to guide created by Spain in the 1500’s that includes several passages on creating towns.

My favorite bit:

The main plaza is to be the starting point for the town; if the town is situated on the sea, it should be placed at the landing place of the port, but inland it should be at the center of the town. The plaza should be square or rectangular, in which case it should have at least one and a half its width for length inasmuch as this shape is best for fiestas in which horses are used and for any other fiestas that should be held.

While acknowledging the irony of being in a guide on how to literally colonize… there are some pretty good ideas here! Selecting sites close to fresh water, orienting streets to maximize light and air, provisions for public space (and fiestas), a regular grid of streets, are all addressed. Because Spain colonized with vigor (to say the least), the impact of these laws is seen across the Americas. St Augustine in Florida is one example, with its port-facing rectangular square and orderly historic grid.

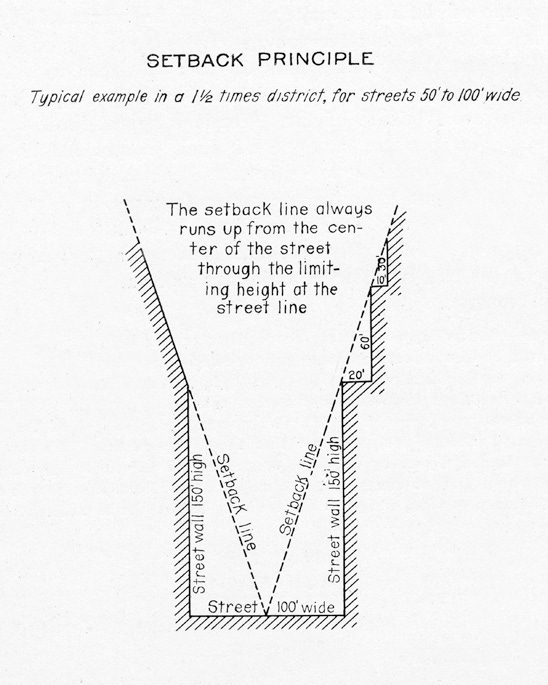

So far we’ve only talked about urban form in 2D — the layouts of plots and streets — but what about 3D? What about buildings? I’d always assumed the ziggurat shape of many NYC skyscrapers was an art-deco thing, but it actually has planning roots.

The above diagram is from NYC’s 1916 zoning law, showing how buildings must setback as they rise to allow light and air to angle into the street. Many examples of this setback-style tower remain today to the point where its considered a standard of art-deco architecture.

I realize I’m jumping all over the place (and over-simplifying a lot) but if you take anything from this let it be the sheer diversity of origins and meanings of city-shapes, ranging from:

Economic expedience: Clear, regular, and predictable property lines

Belief: Feng Shui, Biblical references

Social uses: Public events… like fiestas

Quality-of-life and health: The circulation of light & air, getting around, etc

Power dynamics: Centrality of the ruler’s residence, orderly (and controllable) streets

You’ll notice is there is both art and science at the heart of urban form. If you want to assess the shape of a city there are things you can measure and score but some features will only be explained by cultural beliefs and social practices. I’ll do a future post on the tension between art and science in planning, but I’ll end by saying that using “science” (or at least paying lip service to it) is very popular these days when it comes to planning new urban shapes. The consultant I previously worked for would often use sophisticated analysis software to lay out optimal street patterns for new developments, others have suggested that big data will be the new shaping force.

But of course, a lot of the places I’ve mentioned are beloved for their shapes and the social life they enable, shapes rooted only partially in so-called rational factors. Humans transform our environment more than any other animal (the North American beaver is a distant second). At the end of the day everything we make ends up reflecting our idiosyncrasies. We shape cities to function, but also to express something about ourselves.

I’m in the early stages of this newsletter and trying to grow, so if you like this post please consider sharing it, and feedback is more than welcome. If you want to support the time it takes to make this content consider upgrading to paid. In a month I will launch content specifically for paid subscribers.