This post has been rated N for Nerdy. Sometimes we talk about cool things like block parties and sexy bus design but today is for talking cold, hard, regional planning. You’ve been warned (Next week’s post will be about lost-cities... fun).

Do you know where your city ends? You may know roughly when you pass from one place to another but I mean do you know the literal, actual spot where the city ends and something else begins… legally? Do you realize how vitally important this question is??

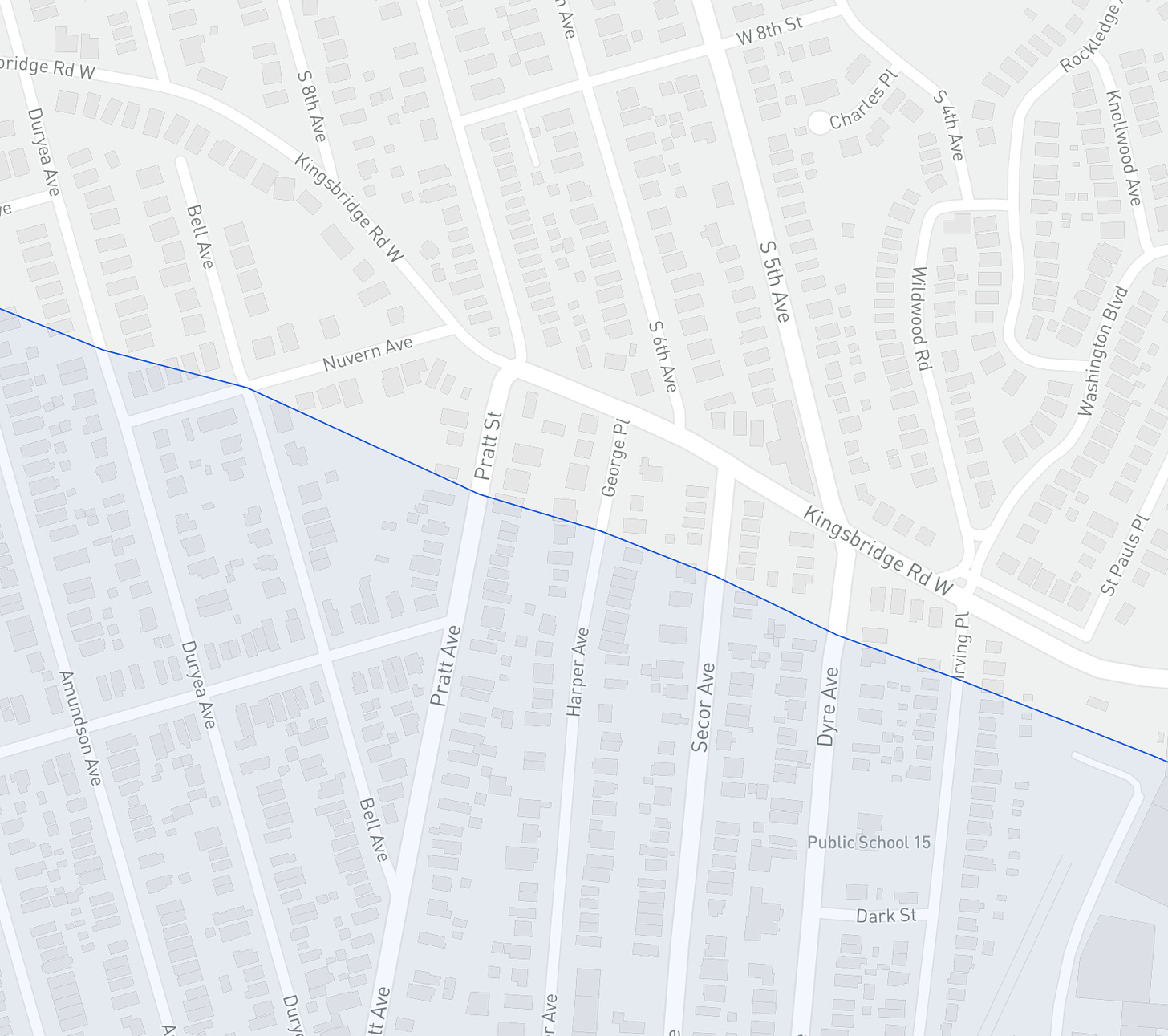

NYC is relatively straightforward. Most of our boundaries are water. New Jersey is across the river, and the river is an obvious boundary. But I realized while writing this I had no idea where our two land boundaries were. Somewhere, the Bronx turns into Westchester County, and Brooklyn and Queens turn into Long Island. Let’s take a look, and then consider why this bit of minutiae is sneakily one of the biggest obstacles to urban planning. Here is where the Bronx turns into Westchester, indicated by the blue.

Except for the border spaghetti around Wakefield, it’s a clean, straight line. But zooming in shows some weirdness. There are places where streets and even backyards are bisected by the border. One end of the street is in New York City while the other is in Mount Vernon.

The border also leads to some jarring name changes, like when 242nd Street in the Bronx turns into West 3rd Street in Mount Vernon.

Here is what it looks like on the ground when West 3rd turns into New York City.

Here is Broadway where New York City ends. The houses on the right, clearly built all at once, step into both cities.

After about an hour of Google Street View, I was getting frustrated. I wanted to see a gateway, a triumphal arch, or at least a sign! So I looked it up. I guess unsurprisingly the sign isn’t on a street, but on the highway. Call me old-fashioned but I feel like entering the Only City In The World should have more gravitas.

I miss the stupid Brooklyn sign of my youth.

Municipal boundaries are invisible to the average person. People live their entire lives at these intersections without much thought. People in Yonkers surely work and spend time in the Bronx. In extreme examples like Minneapolis-St. Paul or Kansas City Missouri and Kansas City Kansas the enmeshing of two municipalities or the straddling of a border may become part of the entire place’s identity. In many ways, this makes perfect sense. Cities have always had hinterlands, outskirts, and suburbs that relate to them but lay nebulously outside their boundaries. Two cities may start life some distance apart but end up right next to each other as each grows towards the other. But these borders become very hard when it comes to city planning and services. School districts, trash pick-up, and police jurisdiction all follow strict geographic boundaries. A guy on Pratt Ave is probably complaining about his high New York City taxes to a neighbor who pays taxes in Mount Vernon.

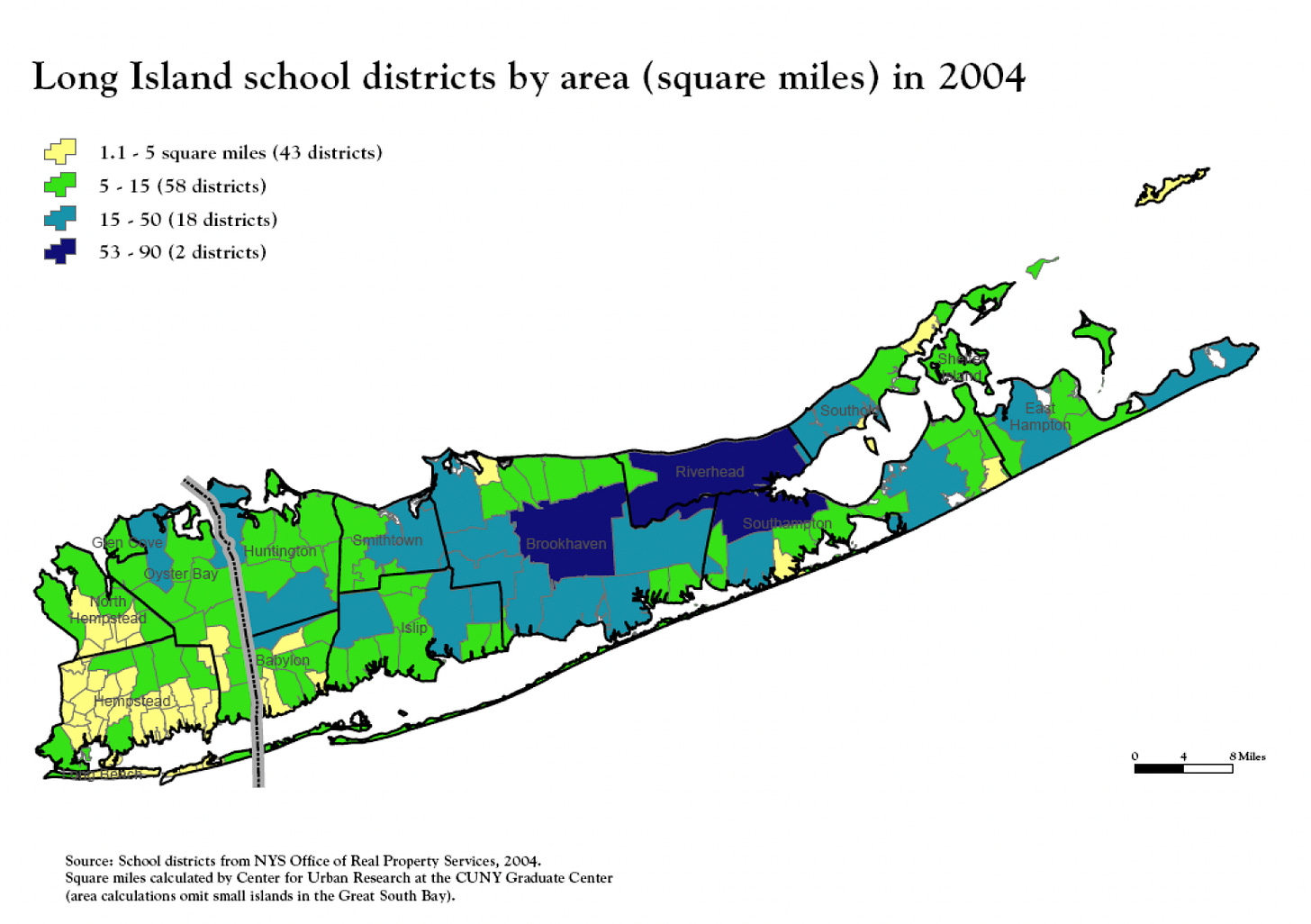

Because of our system of government, America is unique in the impact of all these borders. With our deep-seated suspicion of central government, our system of Federalism was designed partially to ensure that a maximum amount of decision-making and service was concentrated in a more local unit of government— State government — versus central government. Services that are provided nationally or regionally in most countries are intensely local in America. Long Island school districts are a great example of this. There are over a hundred districts many of which are a few square miles and 75% of which serve less than 5,500 students (New York City, by comparison, is 1 school district for roughly 1 million students). Efforts to consolidate these districts have been bitterly opposed by parents worried about school quality, and often by aversion to integrating poorer more racially diverse schools into the wealthier ones.

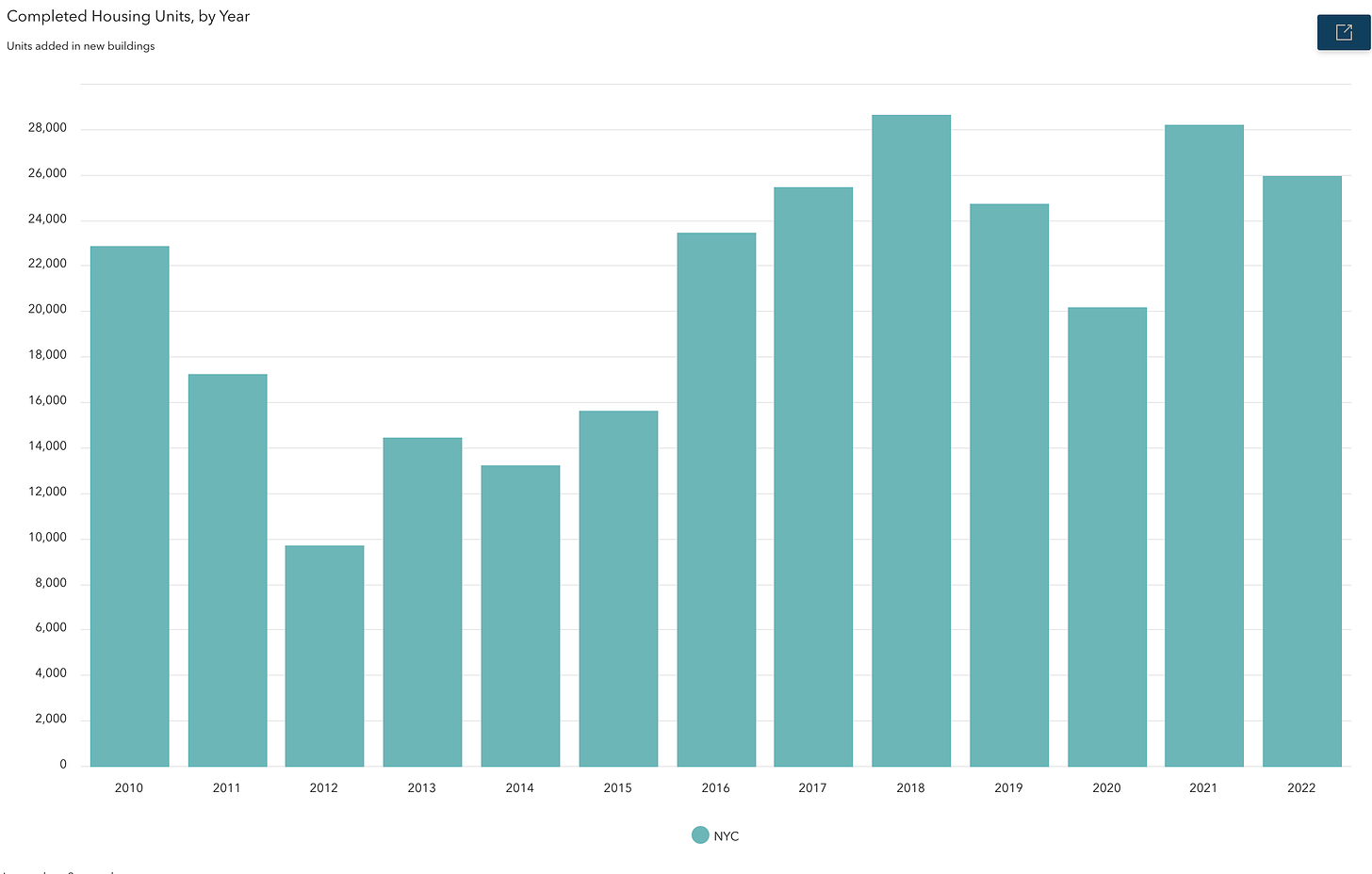

This makes planning very difficult. Financially and operationally it’s a burden to run all these discrete schools, police, and sanitation systems. But these services are straightforward compared to planning for challenges that cross state and municipal lines. Transportation is a big one. Look at the East River. There are 24 crossings for subways, cars, and pedestrians at various points. Brooklyn and Queens are knit legally and physically into the greater city by these 24 conduits. But there are just 6 crossings over the Hudson River between New York City and New Jersey, even though eastern Jersey has experienced tremendous growth partially as a place to live for people who commute into New York. If we ignored state lines, there would be no good reason from a planning perspective that the Subway shouldn’t run into New Jersey, just like San Fransisco’s tangle of BART and MUNI services makes no sense from a user standpoint, only from a legal one. Even inside states, there is needless division. The Long Island Railroad, Metro North, and New York City Subway are all owned by the MTA and within the state of New York, but you need three different tickets to go between them (and forget being able to take one train line from Long Island to Upstate). There is no good reason for this other than they used to be three different railroads and are still partially run as such. Climate change is another big regional issue. Floods don’t care if your coast is technically New Jersey or New York, and you can’t just abruptly end a flood wall or protective measure because the county line is in your way. Then there’s housing. It’s often said New York City isn’t building enough affordable housing, but by 2020, the administration of everyone’s favorite mayor to hate Bill De Blasio had created 50,000 net new units of affordable housing during his tenure. The chart below shows housing created every year since 2010, affordable or otherwise. Hundreds of thousands of houses have been built here and it’s still not enough. But meanwhile….

Right across those arbitrary municipal boundaries are Westchester and Long Island. Many of these municipalities, on the border of America’s biggest city, have produced a minuscule amount of new housing in the past decades, some have even lost housing. In 2008 the government decided that the town of Huntington Beach in Long Island needed to produce 13,000 homes by 2020 to keep up with local (let alone regional) demand. By 2020 the town has built a little over 10% of this goal. When New York Governor Kathy Hochul proposed an end to the zoning laws and development limitations that have kept many of New York City’s surrounding towns low-density, Long Islanders and Westchester residents turned out in droves to save their “Way of Life.” There were some legitimate concerns about schools and traffic. There was also a lot of pure racism and classism about the people who would live in much of the new, multifamily housing the governor was trying to legalize. The proposed package of bills is stalled in the State legislature and unlikely to pass anytime soon.

Viewed from one angle, New York City is failing to produce enough housing, but viewed from a regional lens it is fighting solo against an issue that is plaguing the entire state — and much of the country. Both things are probably true.

Transit, housing, and climate change underscore the degree to which planning issues are regional but American planning bodies and governments are not. So what can we do? State governments are still the most robust regional governments we have. We could advocate for them to take a heavier hand in issues like housing production so individual towns can’t block production the whole state needs. But as Hochul’s attempt shows state involvement is often politically fraught, and sometimes for good reason. The MTA is run by the state, much to the chagrin of New York City residents who are its biggest users and feel historically neglected by its out-of-city leadership. Former Gov Andrew Cuomo forced the MTA to send 5 million dollars to bail out several state-owned ski resorts upstate after global warming impacted their bottom lines…. seriously this happened. We want a system where regional planning can happen but we don’t want to place decision-making and budgetary power too far from the people who use the things we’re planning for most. State governments with a stronger planning focus also don’t solve issues between states.

There are inter-state bodies that focus on specific issues. The Port Authority of NY and NJ exists because state leaders realized it was stupid to plan airport and port infrastructure as two separate states when from the perspective of moving goods and people internationally, NY/NJ is one mega-region. Airports and ports are so expensive and complicated that it was financially ludicrous for the states to compete anyway. The Tennessee Valley Authority was created during the Great Depression to electrify an impoverished slice of the South and is still providing power and infrastructure improvements to the region today. The Army Corp of Engineers, another Federal body, is handling the flood protection for New York and New Jersey’s coastline. Still, things like this are the exception, not the rule, and as these examples show they are often focused on single issues.

A much greater improvement would be to develop an almost new tier of government with the authority to plan broadly for a specific region. If the state is too big, and the city is too small, there is a Goldie-locks middle ground of metropolitan area government that we haven’t really tapped. In a lot of the world, this tier exists. Toronto is a great example. The historic city of Toronto was joined with its adjoining townships on Lake Ontario to form Metro Toronto in the 1950’s. The council was formed of elected officials from each town, city, and suburb and had its own planning office and budget. Transportation, parks, and housing development were put in the hands of Metro while individual municipalities retained some control over schools and other services. I won’t bore you with all the history, but this worked well from a lot of perspectives. The city delivered major transportation and housing improvements in a well-planned fashion and the city grew to the fourth largest in North America. Metro no longer exists because in the late 90’s the Provincial government actually turned the Metro region into one big city— the Toronto we have today. If this all sounds like Canadian mega-government dribble that would never work here, you’re not wrong. But we do have one shining example! The Peoples Republic of Portland has probably the most robust regional government in the US. Portland Metro was created to manage the growth of the city so it wouldn’t impinge upon the natural beauty, rich logging areas, and farmlands of its surroundings. Over time, the remit grew from growth management to delivering regional transit and park systems from Beaverton to Oregon City to the City of Portland proper. It can raise money via ballot measures and did so in 2020 to fund homeless services across the region. Metro is also the only directly elected regional government in the United States.

The average person can’t exactly advocate for more of this type of government, although the Regional Plan Organization has done an amazing job in the Tristate region creating and advocating for regional initiatives. I also realize adding a layer of government isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. But I think it’s clear that our fragmented local governments aren’t equipped to fully address issues that don’t respect their boundaries. The future needs more coordination and regional thinking not less. Right now, in New York City hundreds of thousands of migrants aren’t just crossing state lines, but international ones to try to live and work here. The burden of their presence will likely be felt intensely by a few NYC neighborhoods, while their potential contributions will be limited by a government that lacks the scope to thoughtfully settle them. What many on the right are opportunistically terming as an “invasion” and many even on the left are admitting is a major influx might feel differently if it wasn’t so concentrated. There are, believe it or not, jobs and sites ripe for housing spread around our big region, and places that would benefit from new arrivals and allow them to get on their feet if only we could connect the need to the supply. Sometimes to solve a problem you need to zoom out.

If Mt Vernon is on the northern border of NYC, where is the southern border of “Upstate NY”? 🤔

I kind of love this. I guess I'm a nerd. Or just a native New Yorker who finds geographical borders strangely fascinating but has never applied that fascination to my own city. Thanks for this great post!