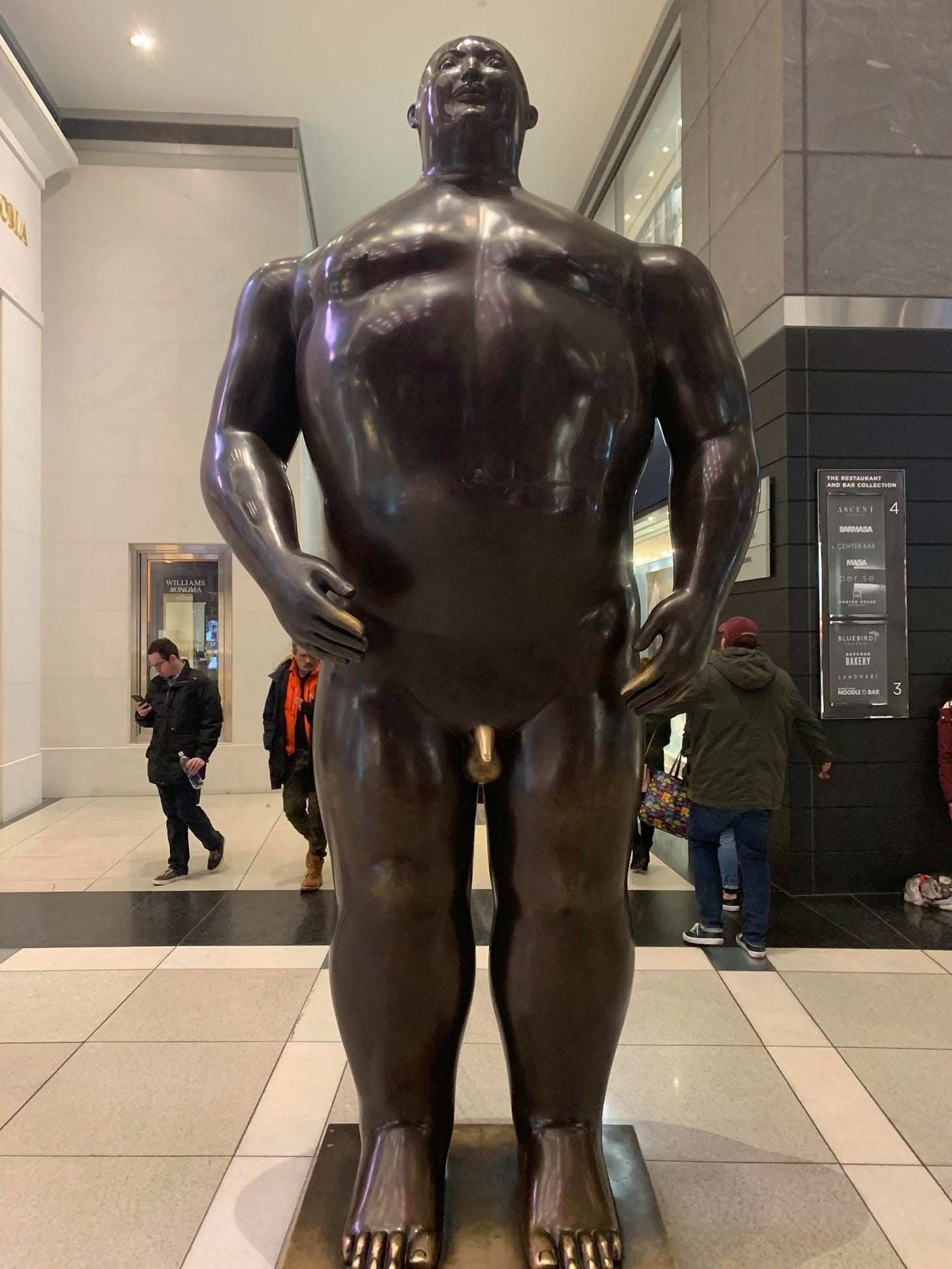

Right after college, I worked at a restaurant across from Lincoln Center, and sometimes during my break, I’d kill time in the mall at the Time Warner Center. Just before the escalator was this rotund statue of a man.

The statue was a dark bronze except for patches that’d been polished to a deep gold: each index finger, the butt cheeks, and the bronze man’s dick n’balls. You can more or less make it out in the picture above. Was this an intentional artistic flourish? Probably not. The bronze on these parts had likely turned this color because people had rubbed them. Good thing the New York Post was on the case.

Years later, I was walking through Soho and was struck by a ghostly silhouette of a pitched-roof building preserved on the side of another building. You could clearly see from the change in the color of the brick where the now-gone building pressed against the larger building on the right.

During peak COVID, a lot of the stoops in brownstone Brooklyn looked like this.

The accumulation of fliers and New York Times Sunday editions still in their blue sleeves strewn across the stoops indicated that no one was home to get the mail, and probably hadn’t been for a few weeks. Given the pandemic and the lack of people in the streets, it was safe to assume that the well-heeled residents of these areas were waiting out the pandemic somewhere else, maybe in second homes across Long Island or Upstate.

Closer to my apartment, the city had just begun its Open Street program and placed metal barriers blocking off Willoughby Ave. Every day while I worked from home, I’d walk along this street during my lunch break and see drivers get out of their cars to slide the barriers aside so they could park. One day I noticed someone had put tennis balls on the aluminum legs of one street’s barriers. I assumed they’d been put there to dull the sound by someone on the block who was working from home, maybe with the window open, and the constant scrape of the barriers was driving them crazy.

The city is readable, within one snapshot of it are signals and signs you can put together to make a hypothesis or tell a story. Urban planning is about the future, but making a plan for the future requires you to diagnose the present and understand the past. Even in a digital era, looking remains one of the best ways to do it. My undergrad studies were in anthropology, a field that thinks deeply about looking, and later in planning school, I was lucky enough to learn qualitative research methods with Prof. Lily Baum Pollans. It might seem silly to intellectualize observation when the vast majority of us have eyes and do it without thinking all the time, but careful looking is a skill you can refine.

The examples I started this post with are what the architect and author John Zeisel would call “traces.”

Traces may have been unconsciously left behind (for example, paths across a field), or they may be conscious changes people have made in their surroundings (for example, a curtain hung over an open doorway). From such traces environment-behavior researchers begin to infer how an environment got to be the way it is, what decisions its designers and builders made about the place, how people actually use it, how they feel toward their surroundings, and generally how that particular environment meets the needs of its users.

Below is a picture of a green space in Brasilia. You can see the auto roads on its flanks, but if you look closely you can see dozens of faint dirt lines cutting across the grass where people on foot have cut across. This kind of trace is called a “desire line,” an unplanned trail caused by human traffic. The planners of this space failed to anticipate that people on foot, not just in cars, would want to cross this space or build actual paths between the points they wanted to travel between.

Zeisel would put desire lines in a bigger category of traces he calls “erosions,” where wear and tear tells you about a pattern of use.

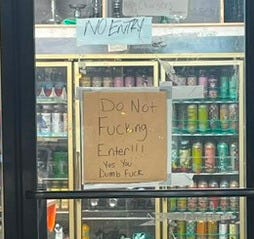

People create traces like this almost without thinking, but intentional changes to the environment, signs both official and unofficial, graffiti, little decorations, or evidence of personalization, are equally telling. Below are two pictures from one Lower East Side bodega. You can safely assume that a) people hang out in the store and b) the operator isn’t exactly a fan of this.

Once you open your eyes to little signals, you can level up to seeing bigger patterns or connections between them. If multiple bodegas in the same neighborhood have signs like this, you might start to wonder if the area lacks accessible indoor spaces for people to hang out. The planner Allan Jacobs suggests that urban professionals keep a series of questions in their back pockets to tease out patterns of traces that can lead to a richer understanding of a place.

A set of relatively straightforward questions carried in the back of the observer's consciousness : Are there patterns and, if so, what are they? Do the patterns fit with expected patterns and processes of urban development for the type of area being observed? Are there new elements that break the older patterns? What is different? Does the rate of change seem fast or slow? What might the new elements suggest about why change is taking place? Are the changes deviations from what one might expect given the location

You can’t always trust your eyes of course. An empty basketball court might lead you to believe that the court is sparsely used, or maybe it’s just the middle of a school day and all the users are in class. Nor is looking the only way to observe. Here is an amazing piece on the soundscape of Mexico City which I found completely transporting.

A chunk of my readers are capital P urban planners but the majority of you are not, so why should you care about this? In addition to being useful, I think deep looking is an immensely pleasurable way to move through the world. We spend so much of our life wishing we were somewhere else that we ignore how interesting where we are can be. The N+1 co-founder Mark Grief wrote an essay called The Concept of Experience that has stuck with me since I read it. More different places, lifestyles, and events are beamed into our eyeballs than any other generation in history. Even for someone who lives in a place like New York City there always seems to be something more exotic and exciting happening somewhere else and to someone else. We start to look at life as a series of what Grief calls “peaks” - times when we were really living: a trip to Italy or that time we met that person at that party. What does this do to us?

“Build peaks, and former highlands become flatlands — ordinary topography loses its allure. The attempt to make our lives not a waste, by seeking a few most remarkable incidents, will make the rest of our lives a waste. The concept of experience turns us into dwellers in a plateau village who hold on to a myth of a happier race of people who live on the peaks.”

The answer to this unhappiness is ironically to treat everything like a peak. “For anything to become interesting, you simply have to look at it for a long time,” wrote Flaubert. Once you become good at looking,g you can summon the intensity of feeling and wonder that your trip to Italy had from anything around you. My grandfather was very good at this. When he was very old, he once pointed to a weed pushing through the concrete outside his apartment and said, “Isn’t that incredible?”

Here is my technique for looking:

Sit down somewhere outside in the city and aim your head somewhere, don’t overthink where.

Your eye will immediately settle somewhere specific, even if you’re staring at a blank wall of bricks, you will probably look at the one brick that’s slightly chipped or the place on the wall where the sun is hitting. Note this location - this is your center point. Now your field of view is set.

Describe what you see. Start with the physical features.

If there are people, switch your focus to them. Try and figure out if there is a pattern in age, dress, etc. If someone breaks the pattern note this. Note also how people are using the physical space— are they in a hurry to get through it or are they lingering?

Invent a story about how what you’re looking at came to be. How old does everything look? Was it made by hand, by nature by machine? Make at least one wild assumption and don’t feel bad about it. Did the people here come from far away or nearby? Pick a person and make up their backstory. Shamelessly judge them, then throw darts at your own assumptions.

Now switch to the future. What is this place going to look like at night? What is this place going to look like in 5 and 10 years? Will the crack in the paint get bigger or is this the type of place where we think someone will apply a fresh coat? If there is a group of old men playing chess and moms in yoga pants, which group do we think there will be more of in the future?

Finally, pick something, anything or anyone, in your field of view that is your “favorite.” Don’t overthink why this is your favorite. Regard this favorite as if it were a work of art.

You have now made a complete experience out of one field of view.

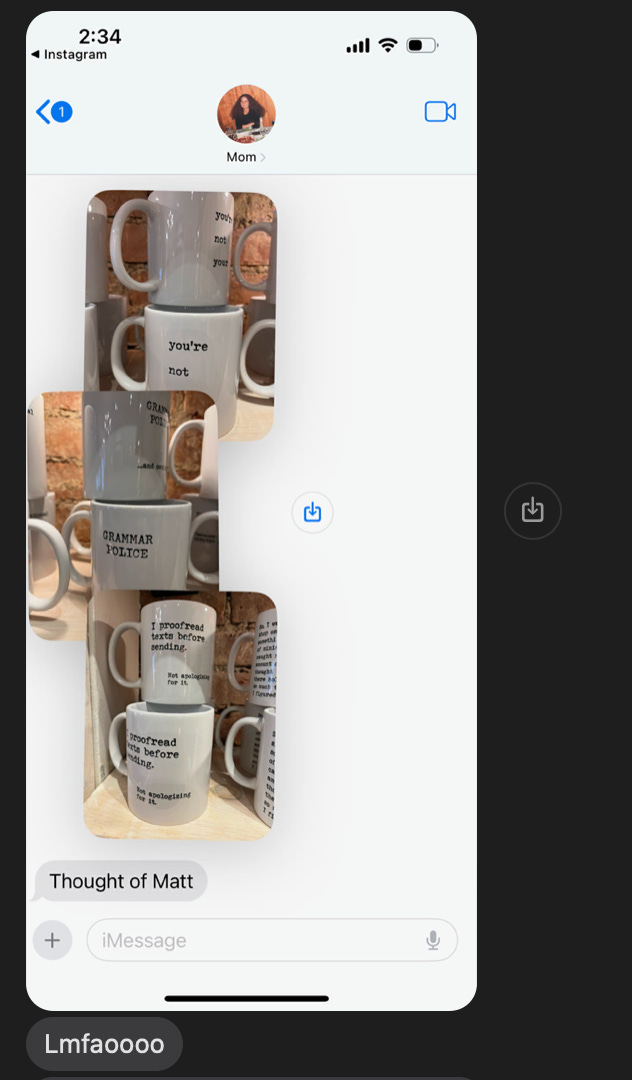

A quick apology:

Over a year of writing, it’s (not its) come to my attention that I. Can’t. Spell. Last week was a low point when I spelled Rockefeller Center as Rocafeller Center. This is especially embarrassing because I have a friggin Rockefeller Center tattoo. You can blame this partially on Jay-Z.

Thanks to all my copy-editors. You keep me humble and one day I will actually internalize your lessons. Until then, you can think of all the spelling mistakes as signs that this newsletter is written by a real human and not AI or big-planning media.

This was an inspiring read, a bit revelatory actually. Thank you.

(Guess where you inherited your atrocious spelling and punctuation.)

Thank you Matt, I enjoyed this immensely, especially from a real human and not AI. Happy Holidays!