There was no lightning bolt moment when I decided I was interested in urban planning. I credit (blame?) a lifetime of living in and being fascinated by a big complicated city. One moment that does stand out was a trip to Mexico City when I was 16. Today, Mexico City is overrun with cool New Yorkers doing their creative director jobs remotely, but in the early 2000’s no one I knew had been there and people mainly asked me if it was dangerous. Growing up I learned almost nothing about Mexico. The Olmec, Aztecs, and Mayans were not included in my classes, nor did we learn about colonization. The only time I formerly learned about Mexico was when we breezed over the Mexican-American war in history class. I entered Mexico with an embarrassingly low awareness of the culture beyond what I gathered from a childhood of Mexican takeout and lurid news reports about immigration, the equivalent of showing up in Italy with all your knowledge coming from American pizzerias.

Because we were capital T tourists we went to the Zocolo on day 1. The oldest part of the city is an undulating mess of Spanish architecture. Buildings tilt and lean on each other, a doorway to a Church appeared to be at a different angle than the ground.

There was a magical realism quality, the forms were familiar but everything was slightly off. We asked the man who ran our bed and breakfast what was happening, and he told us the city was sinking. Mexico City was built on a dried-up lakebed. The city’s water supply came from underground, and as the city drank it lowered the subterranean water table causing the ground to shift in unpredictable ways. The Spanish had drained the lake and dug the wells when they destroyed the Aztec capital that used to be here. This city, he told us, had been built on an island surrounded by water with floating gardens. Even in limited English, this was a powerful image. To Americans, anything European looks “old,” and the idea that this old city was covering up another older city of a completely different style was enchanting.

Later in the trip, we visited the Pyramids of the Sun and Moon several miles from Mexico City and Monte Alban in Oaxaca. Although these were created by different, earlier cultures than the Aztecs, they gave a sense of what was lost. At the time you could still climb the pyramids, and looking out at Teotihuacan was the first time I’d seen a city, ruined or otherwise, free of Western influence. Visits to the Museum of Anthropology and the ruins of Templo Mayor got me hooked on Pre-Columbian cities.

In college, I took classes in the anthropology department on Mesoamerican cultures and learned about the Inca cities of Cuzco and Machu Picchu, Mayan religious complexes, and speculative stories of lost cities in the Amazon. I admit I’m probably guilty of fetishizing these cultures and stories, I have a romantic streak, and many of the things I learned about were so outside any reference point I had that I couldn’t help myself. Did you know the Aztecs thought if you died in battle you spent your time in paradise as a hummingbird pollinating the sun? Did you know the Mayans were possibly the first to use the number zero? Mexico City’s previous form as the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan remained a particular interest, partially because it no longer existed.

Although the Mayans invented writing (possibly only the second or third time in human history that writing was invented independently of contact with another form of writing), this script didn’t catch on with the neighboring Aztecs, and many of the accounts of the city come from the people who destroyed it: Spanish conquistadors. I read the account of the conquistador Bernal Diaz, regarded by historians as one of the more trustworthy chroniclers (The conquistador’s leader, Cortez, produced a highly exaggerated account of the conquest). There is a very powerful moment where Diaz describes looking down into the Valley of Mexico for the first time after months of fighting and negotiating with surrounding Mexican city-states on the conquistador’s trek from the coast inland.

When we saw all those cities and villages built on the water, and other great towns built on dry land, and that straight and narrow causeway leading to Mexico, we were astounded. All made of stone, we thought it was an enchanted vision from Amadis, and some of our men wondered if they were dreaming. It was so wonderful I do not know how to describe the first glimpse of something never heard of, seen, or dreamed before.-Bernal Diaz The Conquest of New Spain

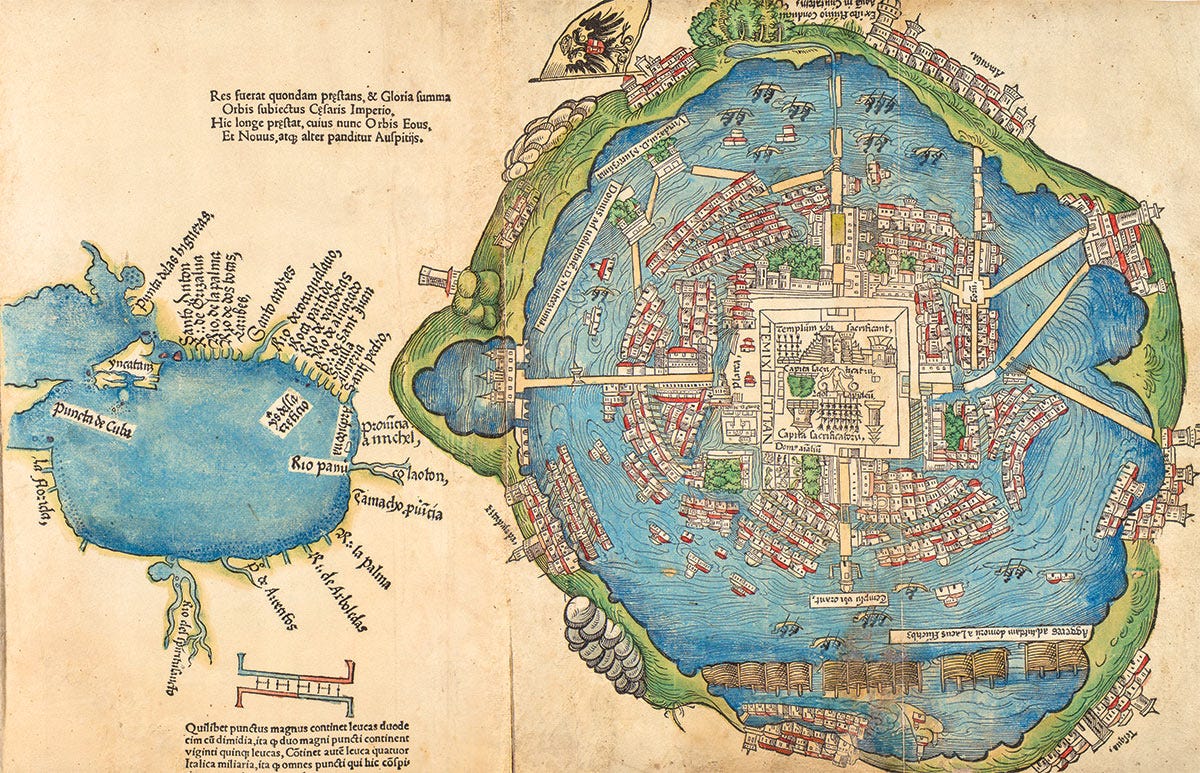

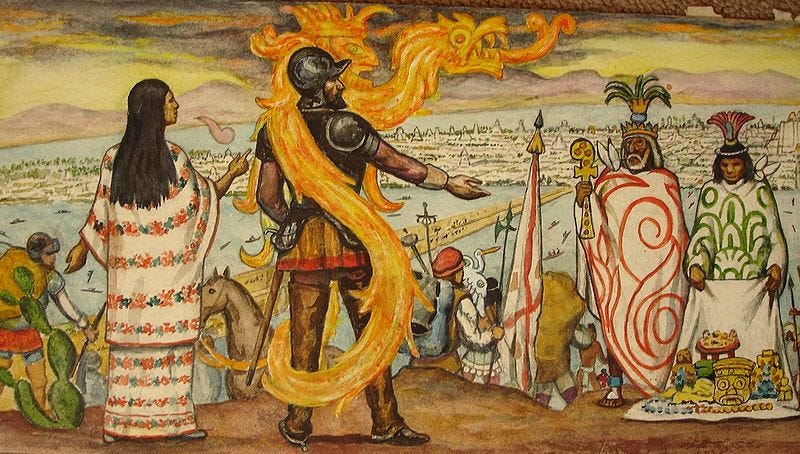

The conquistadors claimed that the city made Seville, home to many of them, look like a village. One conquistador who had served as a Spanish emissary to the Ottomans compared the site to approaching Constantinople from the water. They would have crested the hills and looked over the Valley of Mexico and seen a patchwork of farms, villages, and small cities surrounding a lake ringed with mountains. Into this lake would have extended a spider’s web of stone causeways and bridges converging on a massive city. This city would have been made of richly painted stone structures with plazas, and courtyards arranged along straight boulevards. The Sacred Precinct in the city’s center had 78 buildings and pyramids of various sizes including the 200-foot-tall pyramid of Huitzilopochtli. Two aqueducts brought fresh water from nearby springs to supply a populace that apparently liked to bathe twice daily. Diaz describes an almost Venitian-like system of canals, where villas and gardens opened up onto the waterways so nobles could commute by barge and canoe to various areas. The metropolitan area of this city was estimated to hold a million people, one of the largest urban centers in the world at that time. You can almost hear Diaz’s remorse.

Everything was so charming so beautiful I have no words to express our astonishment, and as I stood I thought there was nowhere else like it anywhere in the world….Today everthing that I saw has been torn down and destroyed, nothing is left standing.

-Bernal Diaz The Conquest of New Spain

This is the earliest European depiction of the city prepared in 1524 and based on a native map now sadly lost to time. Even highly stylized it’s quite impressive.

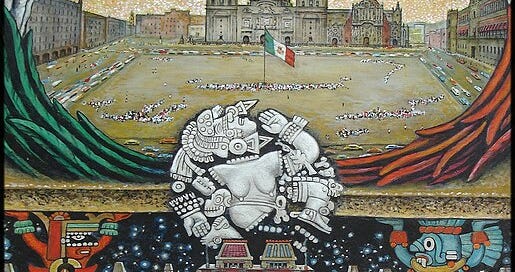

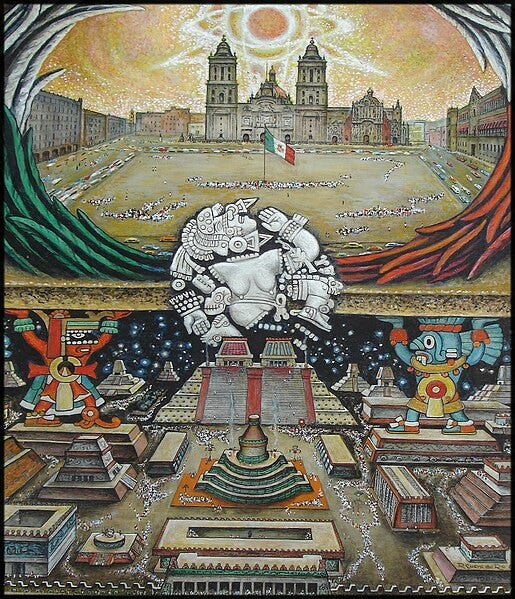

Famed Mexican muralists Diego Rivera and Roberto Cueva del Río both depicted the city. In Del Rio’s first mural, the old city is the foundation of the new. The second depicts Cortez and the Spanish on the city’s outskirts.

The technical artist Thomas Kole has spent a couple of years developing a lovingly rendered 3D model of the city based on extensive research. Many Spanish remarked on the “straightness” of the city compared to the meandering streets of old Europe and you can appreciate the grid pattern through Kole’s work.

These are completely original paradigms of urbanism with potential lessons for the present. In planning and architecture, we are often restricted to the same toolkit of ideas mostly grounded in Western thought or speculative utopian schemes. But Tenochtitlan was built and it worked. The Aztecs developed a system of urban regenerative agriculture that could sustain a massive population. They solved the water problem in a way that the Spanish and contemporary Mexico haven’t replicated. There is one place in Mexico City still where the chinampas—the floating garden system— remain although it’s threatened by pollution and encroaching development.

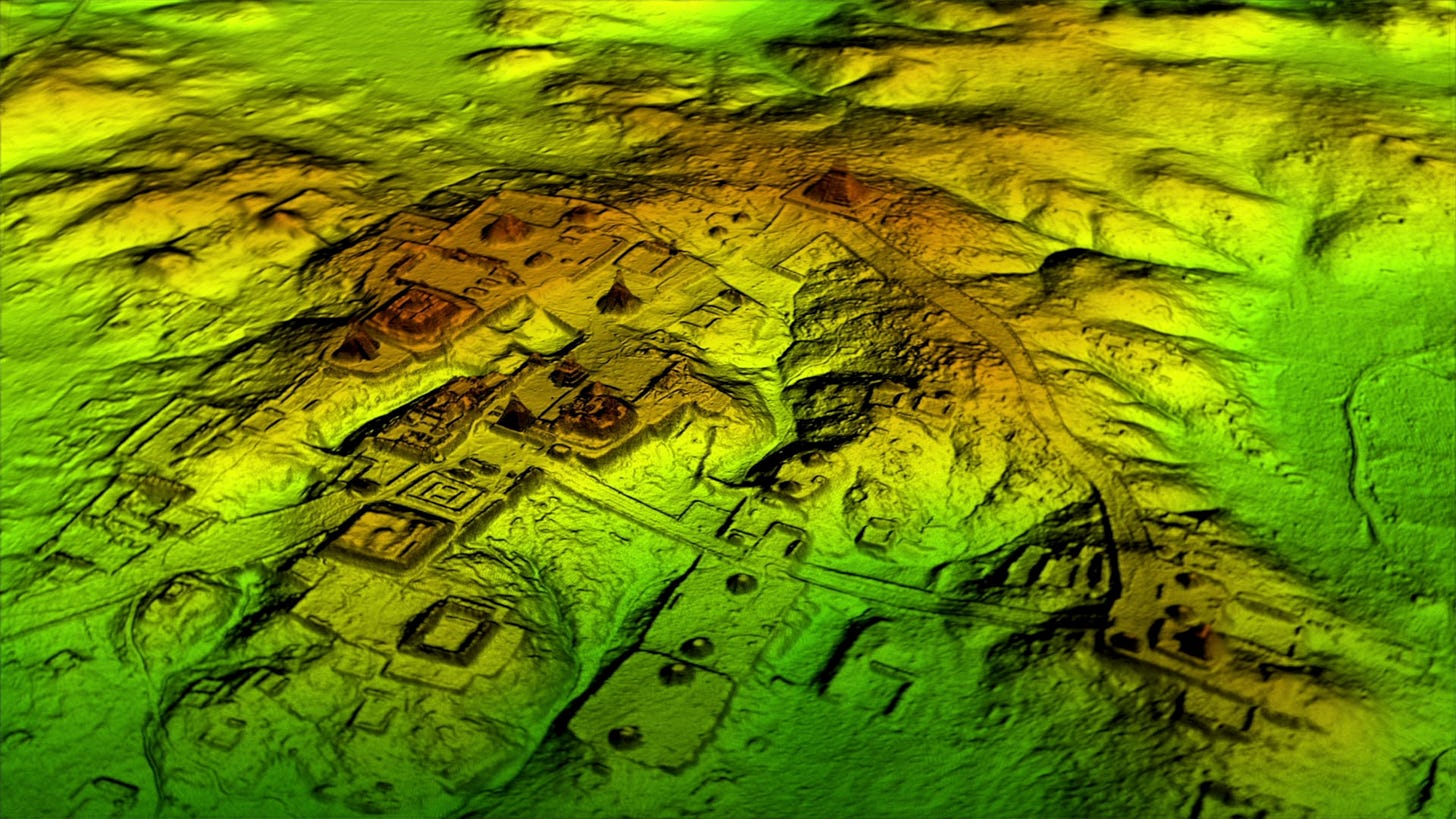

Elsewhere in Mexico and Central America are other rich lessons. My school textbook said that the Mayans built large stone ceremonial centers and some cities but mostly lived in dispersed groups scattered through the jungle. It was thought that the nutrient-poor soils couldn’t sustain settlements larger than a single city or village, and the pyramids we know from places like Tikal and Tulum were the exception. This turns out not to be true. Lidar, a type of ground-penetrating radar, has been used to virtually peel back the jungle canopy and reveal a network of cities beyond imagination. Since 2015, researchers have identified hundreds of thousands of new buildings hidden in the jungles of Mexico and Guatemala linked by 110 miles of highways. The Mayans may have been one of the most urbanized ancient societies to exist.

The Mayans used slash-and-burn farming and wetland and terrace agriculture to cultivate the jungle, moving from place to place during the rainy season and using highways to transport goods from productive places to fallow ones. What had looked like a dense jungle was at one point a semi-tamed landscape producing food for millions. Modern-day Mayans use many of the same techniques. Similar discoveries have been made further south in the Brazilian Amazon, a place thought to be completely inhospitable to large cities. Lidar has revealed a series of interconnected settlements surrounded by a seasonal network of jungle farms. You can see the web of roads extending from the town below. This is the exact region where countless Western explorers died looking for El Dorado. They may have been wrong about the gold but they were right about the cities.

I think everyone who works in the mess of cities should be a little bit romantic about them. Our own cities are constantly being lost and rediscovered. Peel up a floorboard in an NYC tenement and you will probably find something. The lessons from these places— techniques for living, eating, and gathering— and the drama of their discovery and rediscovery expand our ideas about what’s possible. Planning is incredibly bureaucratic but it should be creative, with inspiration and wonder as key ingredients. Italo Calvino wrote in Invisible Cities

At times all I need is a brief glimpse, an opening in the midst of an incongruous landscape, a glint of light in the fog, the dialoge of two passersby meeting in the crowd, and I think that, setting out from there, I will put together piece by piece, the perfect city.

If you want to learn more about the Aztecs and Tenochtitlan I highly recommend the podcast The Rest Is History which has a 7 part series on Cortez, and the book Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs.

In about 1982 in my old apartment on 7th street in the East Village, we pulled back the floor boards and discovered five $20-bills neatly lined up.

Great photos and illustrations!