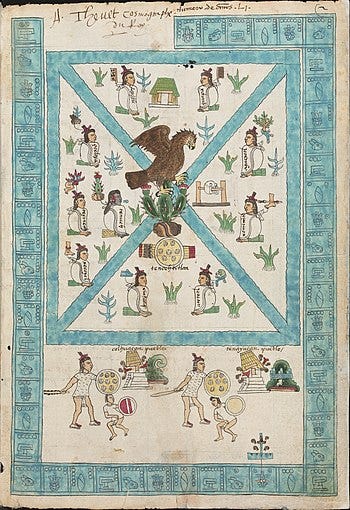

Where does a city come from? A prophecy told a wandering tribe of Nahuatl speakers called the Mexica to build a city at a destined location somewhere in the modern-day Valley of Mexico. The tribe would know they had reached the right spot when they saw an eagle with a serpent in its beak perched atop a prickly pear cactus. They saw this eagle and serpent on a small island in the middle of swampy Lake Texcoco, and that’s where they built their capital, Tenochtitlan, which would become Mexico City. The vision of the eagle and the snake is now the basis of Mexico’s flag.

Archeology has proven that the indigenous people of the Valley of Mexico did actually migrate in waves from what is now the Southwestern US. The wanderings of the Mexica are attested to in sources from the time, but whether you think anyone actually saw an eagle fighting a snake on a cactus is a matter of faith. I believe it.

Even the oldest city was once a patch of uninhabited land. You can explain a city’s emergence in the dryest of terms: Maybe this is where certain key resources were available or maybe this is the point where several roads converge, etc, etc. But throughout history, people have felt a need to take these dry facts and fashion them into a story or myth that bonds their new community with the land. The Greeks and Romans generally insisted that their cities were founded by gods, or at the very least guided by divine intervention. Posiden and Athena clashed over which of them got to claim a particularly beautiful slice of the Greek archipelago. A contest was held to establish patronage, with each god getting an opportunity to present one gift to the inhabitants of the land. Posiden struck a boulder with his trident creating a spring, but the water was salty. Athena produced the olive tree, which provided wood, oil, and food. Thus Athens was founded with Athena as its patron.

The first true city in history, Uruk in Mesopotamia, was founded not by a god but by a king — Gilgamesh. Uruk formed six thousand years ago in what is now southern Iraq, the first place humans shifted to a sedentary, agricultural lifestyle en masse. Through written Mesopotamian poems and legends (written language is something they invented) we hear how Gilgamesh was the first to erect the city’s walls, temples, and streets - features that would have been completely novel when most humans were still nomadic hunter-gatherers. The historian and sociologist Lewis Mumford wrote in The City in History that “the most important agent in effecting the change from a decentralized village economy to a highly organized urban economy, was a king, or rather, the institution of kingship.” Having a leader who could organize public works, collect tribute, and mobilize people was often the deciding factor over whether a city popped up or not, and so the ruler-founder became a popular genre of city origin story.

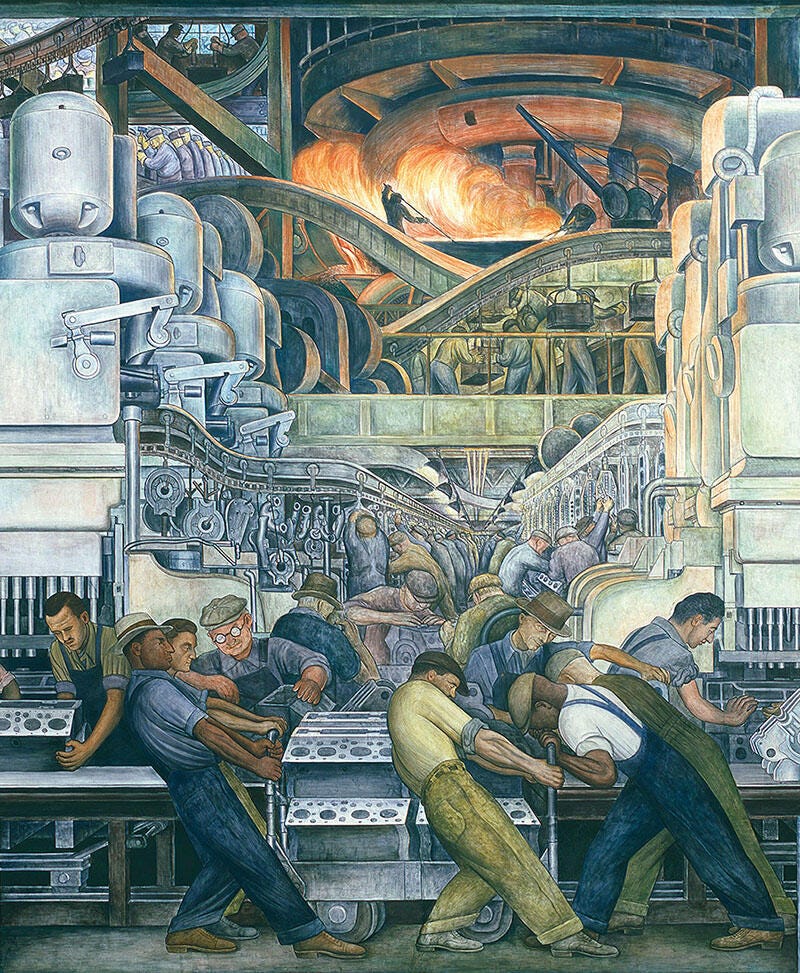

More recent cities lack the drama of kings and gods, but they’re not lacking in self-mythologizing. Detroit was a remote port for grain and fur traveling across the Great Lakes between Canada and the US. When the boats carrying these goods switched to steam power, Detroit workshops began to furnish them with metal parts, and eventually engines. The “Motor City” would become a cultural and economic juggernaut, and the straightforward economic logic of its growth would be turned into a heroic tale through art and culture.

The origin story was further valorized and shaped by branding and marketing - peaking probably with Chrysler’s Imported From Detroit Superbowl commercial and the almost totally made-up storyline of the popular Detroit watch brand Shinola. The documentary Detroit 48202 follows a mailman as he makes his rounds through contemporary Detroit, much of it hollowed out by population loss and neglect. On the way, we meet retired auto workers, civil rights leaders, city officials, and other residents who tell stories about the city’s rise and fall. The specters of government agencies, corporations, and developers loom large in their accounts of why the “disaster” of decline happened to their city. The ghost of Black Bottom, the thriving Black neighborhood bulldozed in the 1960s for freeway construction and redevelopment haunts the film. The struggle of auto workers against Dodge and Chrysler in the 70s takes on the same weight as Athena producing the olive tree. These stories are not myths, they actually happened, but humans are a story-telling and story-loving species, and to hear the facts of Detroit’s history laid out by residents in the movie is a bit like listening to a legend.

The tragedy of the Los Angeles fires has had me thinking a lot about the late writer Mike Davis, who understood that to know a place you had to look not only at its maps and pipes and dates but at the tales people told about it. In his unparalleled accounting of the formation of LA, City of Quartz Davis notes that:

“Los Angeles has always been about the construction/interpretation of the city-myth…Even though Los Angeles’s emergence from the desert has been an artifact of giant public works, city building has otherwise been left to the anarchy of market forces…Compared to other great cities, Los Angeles may be planned or designed in a very fragmentary sense, but it is infinitely envisioned.”

From Spanish Missions to goldrush boomtown, to noir metropolis, and finally, sprawling entertainment capital - a new story has always been available to “explain and historically endorse the emergence of a new order,” in LA. The loss of the city’s premier residential neighborhoods to fires feels not just like the loss of property and livelihoods but also like the death of a certain facet of LA’s myth — the sun-drenched house in the hills or on the palm-lined beach and everything that represents in our collective imagination. What replaces it is yet to be seen, but many of history’s greatest origin stories start with disaster.

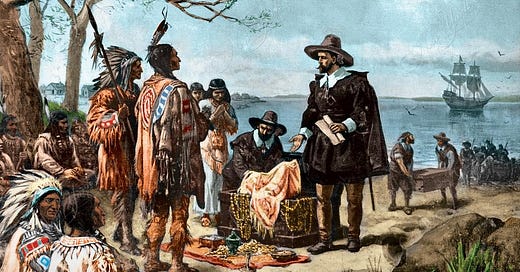

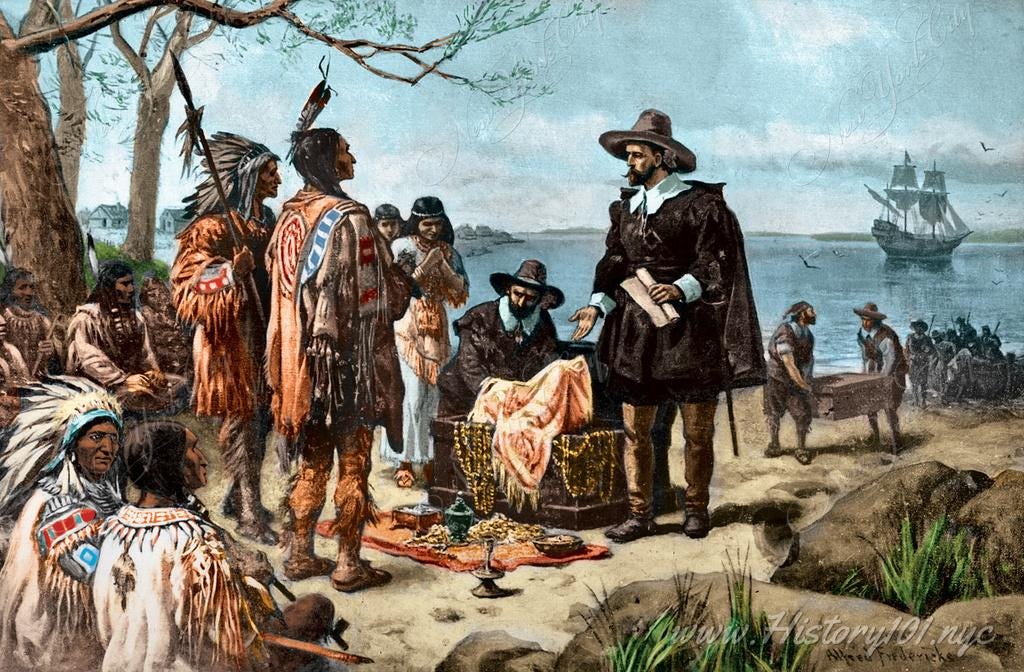

These stories give people a framework for understanding why where they live exists, and maybe why it’s special. My own city, New York, tells what many consider a relatively boring story about its founding. The legend told to pretty much every New York school child is that the Dutch “bought” Manhattan Island from the Lenape tribe for about $24 worth of beads. No one is quite sure who did the buying and for exactly what. The original deed has been lost. But the Dutch were scrupulous in their purchase of other parts of the New York area, carefully recording and filling their deeds and contracts with the East India Company, so historians don’t doubt that some version of the purchase did take place. The Lenape almost certainly didn’t fully understand the contract they were signing and did not share the European concept of land ownership. It’s not exactly an eagle fighting a snake, but I always thought this was the perfect founding myth for New York. It’s a story of sellers, buyers, and (possibly one-sided) negotiations. It has new arrivals displacing old ones. It signals a shift from the cultural or religious-based legitimacy of the Old World — the legitimacy of kings and gods— to what Richard Howe calls the “transaction-based legitimacy” of the New World of contracts and laws. It’s the perfect origin myth for the city that would become history’s greatest collection of sanctioned and unsanctioned speculators, grifters, entrepreneurs, con artists, and strivers — Even if the details are historically fuzzy it’s a good way to explain what we are.

If you enjoyed this post, consider sharing it or upgrading to a paid subscriber to support the time and effort it took to create.

Such thoughtful urban history--and myth and conflict, too. Thanks for giving me lots more to think about, as always.

I can't help but think of contested cities, Khartoum, Kinshasa, Beirut, Jerusalem, Gaza City... places of mythos, history, complexity, conflict, loss, and pain.